Issue:

July 2022

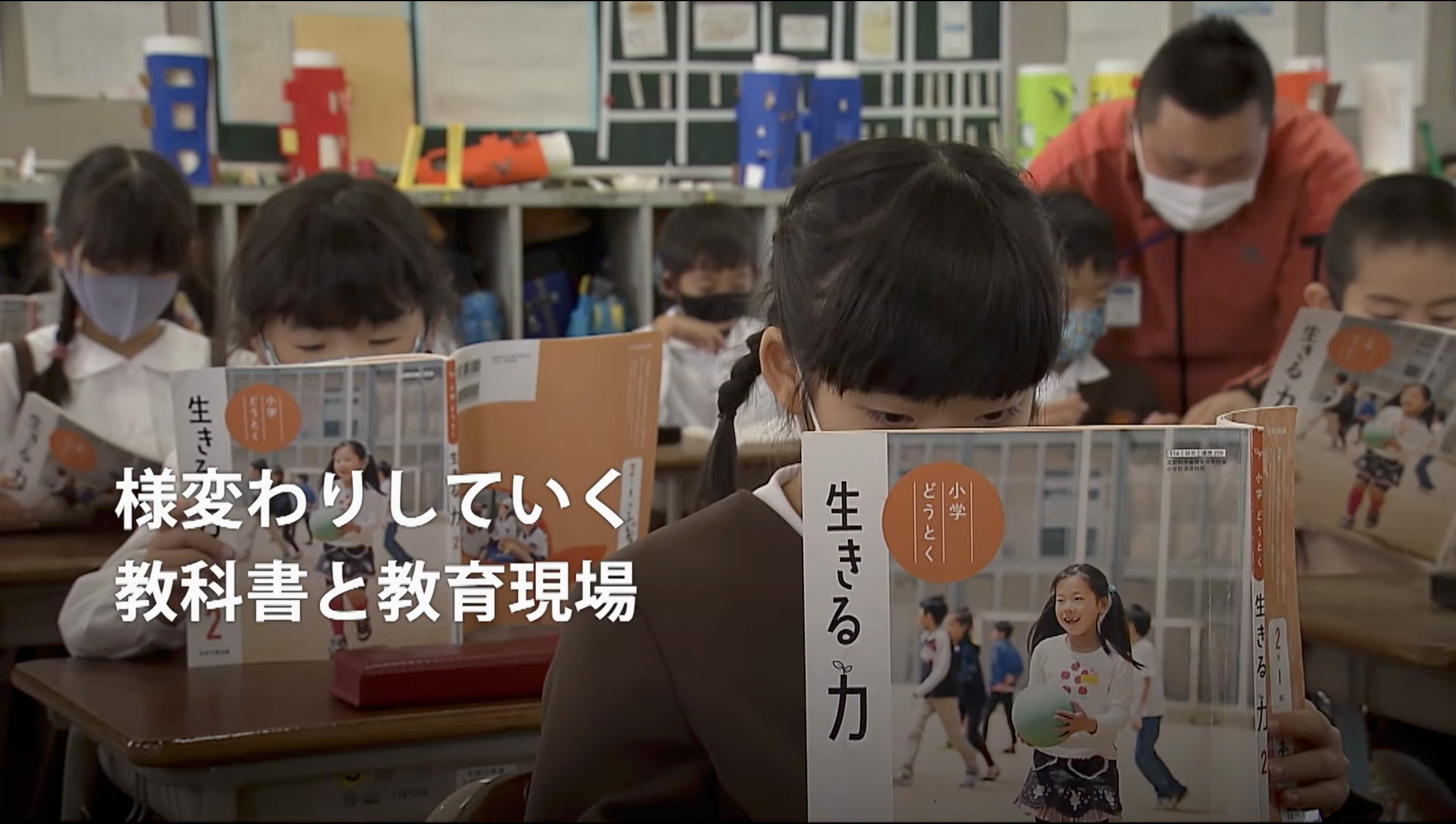

FCCJ event examines nationalist campaign to seize control of the classroom

In 2017, bakeries in Japan reacted with fury after the publisher of a primary school ethics textbook was forced to change the word “bakery” to “Japanese-style wagashi confectioner” in a story about a boy going out and about in his home town.

The alteration to Nichiyobi no Sanpomichi (Sunday Promenade) came after the education ministry made the recommendation out of a “respect for a tradition and culture” requirement in the ethics teaching curriculum before the subject was given official status in primary schools the following year.

The incident went viral online, with many believing the surreal volte-face must have been fake news. Others wondered if it was possible for bakeries to be unpatriotic.

This is probably the most benign of numerous controversies generated by the Japanese government through its direct and indirect attempts to influence national education and, according to critics, rewrite history, one school textbook at a time.

Textbooks in Japan have been a source of controversy for decades, especially in their descriptions of the country’s wartime conduct, including the slaughter of Chinese civilians in Nanking and the use of Korean “comfort women” – both of which are summarized in just one sentence in some of the disputed textbooks.

But unlike most other developed nations, textbooks for primary and junior high school pupils are not written by the education ministry. Instead, the ministry outsources the task to private companies and simply chooses and approves one publication from a shortlist.

Introduced to Japan in 1947 by the U.S. Occupation forces to prevent the Japanese government having direct authority over written accounts of history, the peculiar arrangements for authorizing textbooks has had an unforeseen consequence – fomenting controversy at home and overseas, especially in countries invaded by Imperial Japan during the war.

Critics of the authorization system claim it allows the government to choose only “acceptable” information by sifting out controversial or inappropriate material.

One such critic, the film director Hisayo Saika, argues that the balance in the ideological war over textbooks has shifted to the right.

Education and Nationalism (2022), her award-winning documentary, opens with a scene showing Japanese primary school children learning how to bow.

The work, filmed over several years in collaboration with Mainichi Broadcasting System, then cuts to Shinzo Abe, the former prime minister, whose government accelerated the shift towards nationalistic interpretations of history.

At a campaign stop in Osaka, he tells the crowd: “Creating citizens who carry an identity as Japanese people … means we must make changes in the classroom.”

Speaking at FCCJ in May before the re-release of her film – which now contains additional material – Saika noted that political interference in the name of reform and revitalization had started with the founding of the Japanese Society for Textbook Reform in 1970 and accelerated during the first Abe administration in 2006.

Citing the wagashi shop revision, she said: “Showing love for the country is one of the morals that are to be taught along with 20 others listed such as moderation, respect for discipline, and public spirit.”

Norihiro Yoshida, a member of the Textbook Policy Division at the Japan Federation of Publishing Workers’ Unions, said the government routinely put pressure on publishers. “It’s all on the textbook company to actually make (voluntary) revisions,” he said, adding that some publishers had gone bankrupt after refusing to bow to pressure from politicians.

Tsuyoshi Ikeda, the former editor of the now-defunct textbook publisher Nihon Shoseki, was in uncompromising mood. “If we don’t write about the damage that Japan inflicted and only write about the damage (to Japan) from nuclear bombs and air raids, then (Japanese children) won’t learn about the truth of the war.”

Academic freedom is also under threat in Japan, according to Saika, and attacks against academics have become normalized.

She cites an incident in September 2020, when the then prime minister Yoshihide Suga, denied membership tof the Science Council of Japan to six scientists, allegedly as punishment for their left-leaning political views.

Mitsuko Hirai, who teaches social studied at a public middle school in Osaka, has been labeled “ani-Japanese” by nationalists for teaching uncomfortable truths about wartime history. Hirofumi Yoshimura, Osaka’s populist governor, took to Twitter to accuse Hirai of “pushing her political activism during class”.

Some of her pupils mistakenly mistook her approach as evidence that she liked war. “I hate war, but if we don’t learn about war, then history will repeat itself,” she said. “Information could empower them to stop it if the same situation arose again.”

Data shows hate crimes are on the rise against Japan’s large community of Zainichi Koreans, amid criticism that the government has not done enough to punish the perpetrators. The Diet recently passed a bill designed to address online insults and hate speech, but the law still leaves judges to decide what constitutes hate speech.

Akiko Tagawa the director of a memorial hall dedicated to the Korean community in Utoro, part of Uji city in Kyoto prefecture, said: “I see it as a missed opportunity when there is no mention in textbooks used by children in the Uji area (where Utoro is located] of war crimes that affected Koreans. The only way to solve that is to know and exchange information. Education is the most important tool.”

Defenders of the textbook authorization system – populist politicians, education ministry officials and nationalist academics – say there is no need to teach children about war crimes.

Takashi Ito, professor emeritus of history at Tokyo University, who was interviewed by Saika for the documentary, claims that only Japan has this “masochistic” view of history. “The descriptions make it so that Japanese people can’t have any pride,” he said in the documentary, adding, incredibly: “We don’t need to learn from history.”

Ilgın Yorulmaz is a freelance reporter for BBC World Turkish. She is the Second Vice President of FCCJ.