Issue:

April 2024

The family of FCCJ stalwart Bernie Krisher fought for six years to have his profile in a U.S. magazine corrected

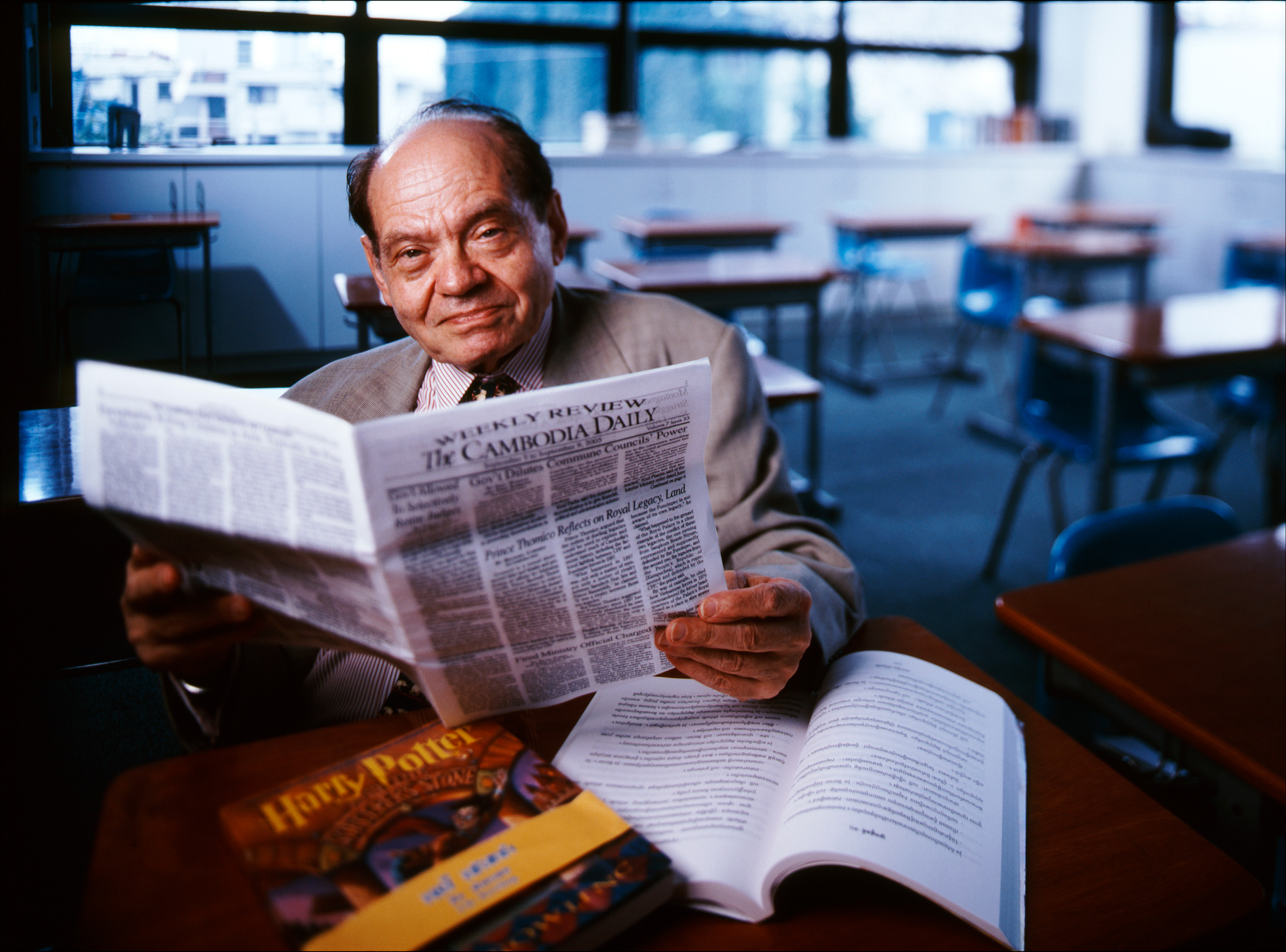

On the morning of December 9, 2017, Debbie Krisher-Steele set up an iPad in her father Bernard’s bedroom and opened an article in the latest issue of the Atlantic magazine. Known as “Bernie” to his family and friends, Krisher was a former bureau chief of Newsweek Japan and Fortune and had been a member of the FCCJ for 39 years. The 2,700-word Atlantic profile detailed his decades of philanthropy and said he had “helped bring free journalism to Cambodia”. But as he read it, Krisher, then aged 87, became “livid” at its inaccuracies, according to Krisher-Steele.

Krisher-Steele said the article read like the writer, Molly Ball, who had by then left the Atlantic for a staff job at Time magazine, bore a grudge against her father. Ball wrote that when she fell ill with cancer in April 2003 when she was working for the Cambodia Daily, which Krisher had founded and managed from Tokyo, he had ignored her requests for help. Ball wrote: “I felt, and still feel, that it was cruel and hypocritical for a purported humanitarian to abandon an employee when she became inconvenient.”

Krisher-Steele says her father told her that he clearly remembered contacting the insurance company to try to help Ball. She subsequently dug out emails on an old computer from May 2003 showing Krisher had sought a solution from insurance officials for Ball's coverage issues. Ball was cc-ed. His message to her stated: "I think you are covered." Ball replied that the issue had already been "solved" through a separate effort. The email exchange showed that Krisher had taken the action Ball had accused him of not taking.

Krisher-Steele says she sent the Atlantic and Ball copies of this exchange, as well as another e-mail offering Ball an additional six weeks’ sick pay, along with a list of a dozen other items they claimed were inaccurate or invaded Krisher’s privacy. On the insurance issue, Ball who was by then working for Time, responded: “We're committed to fixing the piece.” On December 16, 2017, the Atlantic made a few minor corrections and discreetly removed Ball’s opinion that Krisher had been cruel and hypocritical towards her.

However, other parts of the article that Krisher had contested, including details about his career and professional transitions, as well as observations concerning his and his wife’s medical conditions, remained. Despite numerous emails to the Atlantic, in which Krisher voiced his concerns, he received no response. When Krisher died in March 2019, his family felt they had no choice but to continue the fight to have the profile corrected, Krisher-Steele told the Number 1 Shimbun.

“My father’s whole legacy was to establish responsible journalism in Cambodia. He believed that journalism’s responsibilities are to be accurate and truthful, and also to be fair and impartial. That was the irony of the whole thing: that he would read this article about himself at the end of his life that was written by someone who apparently had a grudge against him, peppered with many inaccuracies that injured his reputation. When he confronted the editors at the Atlantic, they refused to engage with him.”

In December 2019, the Atlantic and Ball, based in Washington, D.C., received a copy of the lawsuit and were served with a summons from the Tokyo District Court. The lawsuit claimed defamation and invasion of privacy (Ball had secretly recorded conversations and taken photos inside Krisher’s Hiroo apartment). The article had damaged their father’s reputation, the suit said, adding that Ball's narrative had “stitched together unrelated facts and quotes spanning several decades, (leading) readers to form false and injurious impressions of Krisher”.

The dispute ended in January this year with a settlement for the family that resulted in multiple corrections to the online version of the article, and the destruction of all digital and physical copies of the photos that Ball took of Krisher.

That denouement, wrote Erik Wemple in a review of the case for the Washington Post, “helped to furnish a useful lesson in how U.S. media companies fare when they cannot fall back on the ironclad legal protections they enjoy in the United States”. It was also, he added, “a window into an embarrassing fact-checking breakdown at a top American media outlet.” The Atlantic has declined to comment on the case.

To win a libel suit against the media in the U.S., public figures such as Krisher must prove “actual malice”, meaning the evidence should show that a journalist knew the defamatory facts were false or acted with reckless or malicious disregard for the truth. The burden provides strong protection for the press: in 2017, for example, a federal judge dismissed a defamation lawsuit by the politician Sarah Palin against the New York Times because it failed to meet this legal standard.

The key task of defamation law is “to reconcile society's interest in robust and truthful speech with the individual interest in reputation,” noted Ellen M Smith in a paper for Michigan Journal of International Law. This balance tips in favor of press freedoms in the U.S., she adds, while Japan leans toward protecting individual interests. “The court in Japan looked at the duty of care by the publisher and reporter”, says Krisher-Steele. “Whether the facts were true or the reporter had adequate basis to believe that the facts were true. Did they properly check their facts before publishing them?”

Defending the lawsuit in Japan (where the Krishers lived) was tricky, involving two legal teams working in different countries and in different languages, and hundreds of translated documents. There was at least one precedent: in 1989, Time lost a defamation suit after it was found to have distorted the opinion of a Japanese doctor who was quoted as saying that abortions are so common in Japan that “it is like having a tooth out” (Time had dropped the words “this suggests for some people” from the start of the quote).

The Atlantic and Ball had six months, post-summons, to decide whether to settle or defend the case in Japan (ignoring it would mean accepting a default judgment). It’s not clear why they decided on a costly fight. A panel of three Japanese judges found mostly in favor of the Krishers and encouraged them to settle, resulting (according to Krisher-Steele’s count) in 16 corrections to Ball’s original article. Much of the deleted content was deemed defamatory or false (in the settlement, neither side admits to wrongdoing or liability). “We suggested it would be easier to retract the article, but they declined,” she says.

“Initially we weren’t going to sue because we thought once they look at the facts their instinct will be, ‘Of course we’re going to correct it’. But they didn’t”, she continues. “They could have saved six years and a lot of money by just fessing up.” She says the Atlantic profited from the article and broke copyright on a photo used to illustrate it. “They were so disrespectful. If you made a mistake, say you’re sorry. I’ve never had an experience like this, ever. My only goal was to set the record straight.”

All this might suggest that Japan is legally a softer touch when it comes to proving libel. But the suit, says Krisher-Steele, was not about the author’s opinion of her father; it was about due diligence and care for facts. “It was about journalism and journalism ethics ... could the journalist prove what she was saying?” she says. One anecdote quoted in the story, and removed as part of the settlement, claimed a young woman at Newsweek was driven to a nervous breakdown by Kirsher’s “imperious and bullying” personality. It turned out to be double hearsay

Another line in the story said that Krisher’s boasts to have been the only reporter to have interviewed Emperor Hirohito were a “typical Krisherian exaggeration”. Krisher “never said that to anyone, including Ball”, says Krisher-Steele. “He was the only journalist to have been granted a 32-minute one-on-one Q&A with Emperor Hirohito on the record for publication. It was considered a scoop of a lifetime. That was no exaggeration.” In the settlement, the Atlantic removed that line and replaced it with a quote from an interview he gave about his Hirohito interview to another interviewer in 1989.

Krisher-Steele says the manner in which Ball insinuated herself into the Krisher home in Hiroo still stings. The interview was not pre-arranged and Bernie was very ill. “He can’t see her because he’s not wearing his glasses, and he can’t hear her because he’s not wearing his hearing aid. He doesn’t remember her. She recorded the whole thing. She was also photographing him secretly in his bedroom, without his consent and against his will. We learned about this after the fact. It was bizarre and unethical.”

Atlantic correction: This article originally stated that Bernie Krisher failed to assist the author with a health-insurance problem in 2003, when he was her employer. The article noted that Krisher denied this, saying he had appealed to the insurance company without success. After the article went to press, Krisher located emails from that time showing that he had attempted to help the author, but that the problem had by that time been resolved. The article also stated that Sihanouk asked Krisher to give Cambodia a newspaper; in fact, he asked Krisher to help rehabilitate the country. Lastly, the article said that two alumni ofThe Cambodia Dailywon Pulitzer Prizes. Only one did. We regret the errors. On January 19, 2024, as a result of a lawsuit filed by Krisher’s children in Japan, the article was further updated to remove certain private details regarding Krisher’s and his wife’s health; to remove characterizations of the insurance offered byThe Cambodia Daily and of Q&As Krisher conducted; to clarify the context of Krisher’s interview of Emperor Hirohito; to remove an allegation made by a former colleague of Krisher’s, add denials by Krisher’s children and two former colleagues, and add detail about Krisher’s firing; to clarify that Krisher was the chief editorial adviser, not founder, ofFOCUS, and had previously misidentified the person featured in a photograph; to clarify that the non-payment ofThe Cambodia Daily’s cable bill was not Krisher’s responsibility; to clarify that Kay Kimsong’s experience facing defamation charges; and to clarify a question asked by the author.

David McNeill is professor of communications and English at University of the Sacred Heart in Tokyo, and co-chair of the FCCJ’s Professional Activities Committee. He was previously a correspondent for the Independent, the Economist and the Chronicle of Higher Education.