Issue:

August 2023

Japanese media lean into Kabuki scandals in wake of Ennosuke IV's attempted suicide

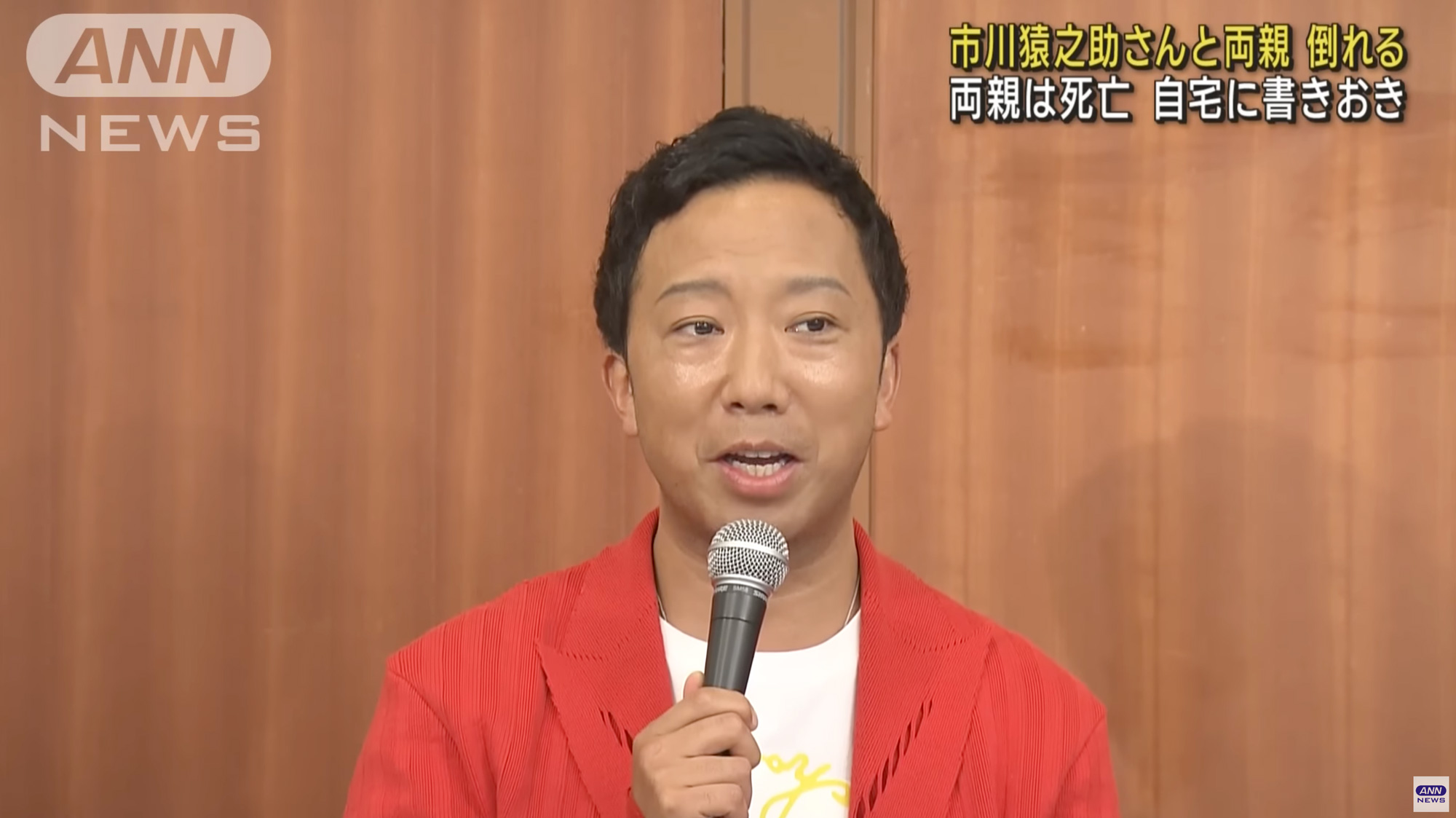

The matinee performances of the month-long July program at Tokyo's Kabuki-za, the prime venue in Japan for Grand Kabuki, was headlined by Ichikawa Chusha IX, an actor most people know by the name Teruyuki Kagawa. The play Chusha starred in was Kikunoen Tsuki no Shiranami, a specialty of Chusha's father, Ichikawa En'o, who revived it in 1984 after a 164-year hiatus. During his heyday, En'o, now retired as an actor and director, was known as Ichikawa Ennosuke III, and, in fact, the heir to this hallowed name, Ichikawa Ennosuke IV, was originally scheduled to star in the July production, but couldn't because he was under arrest for assisting in the suicide of his mother. On May 18, Ennosuke was found unconscious in his home. His parents' bodies were found on a different floor of the house, his mother dead and his father dying. Ennosuke later told police that he and his parents had planned to die together, but he apparently didn't take as many sleeping pills as they did. On July 18, he was served a fresh arrest warrant for assisting in the suicide of his father.

Ennosuke IV is the nephew of En'o – Ennosuke's father was another Kabuki star, Ichikawa Danshiro – and considered by Kabuki aficionados to be one of the great modern practitioners of Japan's unique theatrical art form. Chusha, on the other hand, has not been a Kabuki performer as long, and many fans thought that a more experienced actor should have taken the lead in Kikunoen, which, as an Ennosuke III production, contains lots of gaudy effects and thus requires a special set of skills. According to a report in the tabloid Yukan Fuji, Chusha did better than expected, and, in fact, the Kabuki-za performance allowed him to re-enter show business after being blackballed in the wake of a scandal that emerged last summer. However, his banishment from conventional acting and TV presenting – as Teruyuki Kagawa – continued. The proscriptions did not extend to the world of Kabuki, though many Kabuki actors readily flit back and forth between the two entertainment realms.

In a July 2 article that appeared on the Digital Friday website, entertainment reporter Toshio Ichikawa (no relation) theorized that had Ennosuke IV not assumed the Ennosuke name in the first place, the group suicide probably wouldn't have happened. That's because En'o as Ennosuke III established a unique position in Kabuki, and by assuming the mantle his nephew, previously working under the name Ichikawa Kamejiro, had to live up to that reputation. Kagawa/Chusha, who is En'o's biological son, would normally be expected to take over the family business, but did not because of his own history. Kagawa's mother was Yuko Hama, a famous actress in her own right as a star of the Takarazaka Revue, which, being an all-female musical theater company, mirrors Kabuki, whose performers are all male. However, shortly after Kagawa was born, En'o left Hama for another, older actress, Murasaki Fujimori, with whom he had had a relationship since he was a teenager. Kagawa was raised by Hama alone, and, while he wanted to be close to his father, En'o refused to see him, effectively disowning him. Kagawa then went on to a successful career as a conventional stage, movie, and TV actor, and occasionally would attempt to contact his father, but En'o ignored his entreaties.

Eventually, after Kagawa himself became a father, Fujimori intervened and convinced En'o to meet him and his new grandson. They became closer, and Kagawa, along with his son, would often visit En'o in his dressing room during performances. He told his father he wanted to be a Kabuki actor, too. Normally, Kabuki actors start training when they are children, but Kagawa was already in his 40s. Knowing it would be too difficult to teach his craft to a middle aged man, En'o objected. Fujimori was also against it, not so much because of the learning curve, but because Kagawa had not grown up in the Kabuki world and did not know what it entailed. It would be especially difficult if Kagawa joined his father's Kabuki school, called Omodakeya, which En'o, as Ennosuke III, had made into one of the most successful in Kabuki history by flouting tradition. In fact, “Ennosuke Kabuki”, with its flashy entertainment values that relied on extensive wire work, pyrotechnics, and lightning-fast costume changes, more closely adhered to the original spirit of Kabuki, which was developed for the hoi polloi as an alternative to the refined art of Noh, which was for the upper classes. Nowadays, Kabuki has become calcified in tradition, but Ennosuke III's productions, especially his trademark Super Kabuki shows, were blockbusters. Ennosuke IV even went further, adapting some manga, such as One Piece, and video games into Super Kabuki stage productions that proved very popular. Ennosuke III could not have done all this without Fujimori, who was instrumental as a mediator between him and Shochiku, the all-powerful entertainment company that supervised commercial Kabuki.

En'o effectively had propped up the world of Kabuki for years, and when Fujimori died and En'o was forced to retire due to ill health, the fortunes of Omodakeya started to shift. According to Ichikawa's article, in his bid to become a Kabuki artist in his own right, Kagawa leaned on his cousin, Kamejiro, who helped him enter Kabuki and take on the name Chusha. Many assumed that Kagawa would eventually take the Ennosuke name, but Kagawa insisted the heir be Kamejiro, knowing that he himself could never head Omodakeya and its stable of actors and artists. At the same time, Kagawa's son, who had already entered Kabuki as a child, took the name Ichikawa Dango.

Shochiku took advantage of this triple PR coup and promoted their 2012 name-succession ceremonies to the mass media, which took the bait. Shochiku thought the publicity would spur Omodakeya to even greater heights, but, in the end, it proved to be the start of the school's downfall. For one thing, it lost one of its biggest stars, Ichikawa Ukon, who in many ways was the real heir to En'o's unique style, having trained as En'o's understudy for years. He knew En'o's gestures and techniques in his bones, but when Kagawa joined Omodakeya, Ukon saw the writing on the wall and left the school for another, Takashimaya, changing his name to Udanji in the process. It was a huge loss for Omodakeya because Ukon was very popular. His son, however, remained in the school, assuming his father's old name.

Ennosuke IV, it turned out, was not suited to run Omodakeya either. An article published by the weekly Josei Seven following his arrest quoted an anonymous Kabuki insider, who said that Ennosuke was “spoiled” by his ascension to the top of the most lucrative school in Kabuki, and while he was exceptionally talented, he had no true comprehension of the world outside of Kabuki. Within the world he inhabited he believed he could do anything he wanted. That world easily put up with his arrogance, but when Josei Seven reported his serial sexual abuse and power harassment of staff and others, Ennosuke lost his bearings and, on the day the article was published in May, coerced his parents into committing suicide with him. Once his sins were pointed out in public, he couldn't handle the criticism. Even a representative of Omodakeya told the magazine that Ennosuke's actions demonstrated no sense of responsibility. If the harassment claims were true, for the sake of the school and Kabuki in general he should have addressed them sincerely and apologized to the injured parties, who, he added, never intended to report the abuse and harassment to the authorities. Kabuki, this representative said, is a very forgiving world, unlike conventional show business. He could have continued his career unchanged, but instead he panicked and tried to kill himself, and likely will never be able to return.

But another insider believed that Ennosuke had been moving away from Kabuki well before the scandal. Despite the media fervor over his succession, his subsequent performances were not selling as many tickets as they had in the past, and he started doing more movies and TV for big money that fueled a dissipated, lavish lifestyle. Nevertheless, this person said, the Kabuki world needs the Ennosuke name, even if only behind the scenes.

The cynical upshot of these circumstances is that since the arrest and the attendant media attention, Kabuki attendance has increased, thus justifying the old adage that there's no such thing as bad publicity.

Consequently, in addition to providing new opportunities for emerging young stars, it gave Chusha a chance to shine in a leading role, which was extremely important to him since he may already be washed up as a conventional actor-talent due to his own poor behavior. Last August, the weekly Shukan Shincho reported an incident from 2019 in which a drunken Kagawa groped a hostess in a Ginza bar, removed her bra and passed it around to friends, and forced her to kiss him. The traumatized hostess filed a lawsuit against the owner of the bar for failing to prevent the incident, but later withdrew it. No criminal charges were ever filed. Kagawa apologized for the incident during one of his regular TV presenting jobs, but over the following months he lost his lucrative spokesperson gigs for a number of companies, including Toyota and Suntory, and was dropped by TV stations he worked for as an actor and presenter.

Kagawa/Chusha's taking over for Ennosuke IV in the July Kabuki-za program proves the anonymous insider's aforementioned claim that Kabuki is more forgiving of bad behavior than the larger Japanese show business world, and some of that dispensation is connected to Kabuki's image of itself as an exceptional calling. Kabuki stars are expected to sleep around and act like jerks to their staff because all life's experience is grist for the creative mill, and, given a Kabuki star's grueling schedule, he is allowed to blow off steam. The increased public opprobrium engendered by the #MeToo movement has tempered this outlook to a certain degree, which could explain Ennosuke's extreme reaction, but, in the end, Kabuki is thought to operate on its male stars’ egos and whims.

It also operates on seshu, the idea that positions within the Kabuki world are hereditary. Indeed, outside of the Imperial family, no institution in Japanese society is as hereditary-bound as the Kabuki world, though it is not necessarily based on blood. Some of Kabuki's most illustrious stars, such as Bando Tamasaburo, considered the greatest onnagata (actor specialing in female roles) of the modern age, was not born into a Kabuki family, but was adopted into one. En'o, in fact, was quite dismissive of the whole family-based Kabuki succession system, preferring to cultivate talented young people regardless of their background as skilled craftsmen who could carry on the Ennosuke style. Nevertheless, when it came time for him to bestow his name on a successor, he chose Kamejiro, because of the blood relationship. Had Ukon remained in Omodakeya after Kagawa entered, En'o may have chosen him instead, because, like Kamejiro, he was also a nephew, but we'll never know. Will Chusha inherit the mantle of his father's glory, now that Ennosuke IV is, for all intents and purposes, out of the picture? Given Chusha's significant lack of experience, that may be beyond the pale, and insiders feel that the most obvious solution is to eventually pass the Ennosuke name onto Chusha's son, Dango, now 19 and raised as a Kabuki actor in the Ennosuke style.

The convergence of these various scandals have made a lot of fans question if there is any future for Kabuki. Obviously, the authorities would never countenance the demise of a signal Japanese art form, but it seems likely that things will have to change, most likely a further opening up of the Kabuki world to people with no familial connections and a more liberal-minded approach to content and stylistic innovation. There is even talk about allowing women to enter the world of Kabuki as more than just the occasional novelty. Noted film and stage actor Shinobu Terajima, herself the daughter of a Kabuki actor and whose French-Japanese son is now undergoing training as a future Kabuki star, is being touted by serious Kabuki folk as a regular performer, a development that would shatter the art form's most contentious taboo. Traditionalists say this is a cynical move, as well, but it's likely Shochiku wouldn't oppose it if it leads to higher ticket sales, and most certainly it would – at least for a while.

Philip Brasor is a Tokyo-based writer who covers entertainment, the Japanese media, and money issues. He writes the Japan Media Watch column for the Number 1 Shimbun.

Sources

https://news.yahoo.co.jp/articles/6b0249f0e3802ca9905082c8b11fe29807e0bfd7