Issue:

WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN POST-WAR JAPAN

Beate Sirota Gordon following a 2011 screening of

“The Sirota Family and the 20th Century”

(シロタ家の 20世紀 / Shirota-ke no nijyu seiki /

Dir. Tomoko Fujiwara / 2008)

at the Japan Society in Manhattan, New York City.

VICKI L. BEYER

When Douglas MacArthur arrived in Japan in August 1945 to head the Occupation as Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, he brought a mandate to “demilitarize, democratize and eliminate the basis for

economic aggression”.

MacArthur moved swiftly on the first two, even conflating them when he called on the Diet later in 1945 to revise the Election Law to give women the vote. Apparently when his staffers warned him that Japanese men would not favour female enfranchisement he replied to the effect, “I don’t care. I want to discredit the Japanese military. Women don’t like war.”

MacArthur got his way. The revised Election Law, giving the vote to “all men and women aged 20 and over”, was promulgated on December 17, 1945, and Japanese women voted for the first time on April 10, 1946.

A key figure in helping Japanese women understand their new right of suffrage and encouraging them to use it was Lieutenant Ethel Weed (1906-1975), an American Women’s Information Officer, who hosted a weekly “Women’s Hour” radio program that often addressed political issues. Weed also toured Japan prior to the 1946 election urging women to vote; 13.4 million women obliged, and there was a surge of women candidates. As a result, the expanded electorate of 1946 sent 39 women to the House of Representatives, 8.4% of the body.

Peak representation

Sadly, the 1946 return remains the highest proportion of women ever to be elected to the Diet. By the next house election, in 1947, women representatives dwindled dramatically to one or two percent and stayed there for the next 50 years. This in spite of the promulgation on May 3, 1947 of the “Peace Constitution”, in which Article 14 states: “All of the people are equal under the law and there shall be no discrimination in political, economic or social relations because of race, creed, sex, social status or family origin.”

What happened?

There are various theories about why women haven’t taken a more prominent role. Many of them focus on the deeply entrenched paternalism of Japan and the “men’s world-women’s world” bifurcation that was popularized during the post-war high-growth period. There is even the linguistic subordination of women. The theories, in a sense, represent a vindication of the view of a 22-year-old “slip of a girl”1 working for GHQ during the Occupation who found herself involved in drafting a new constitution for Japan in early 1946.

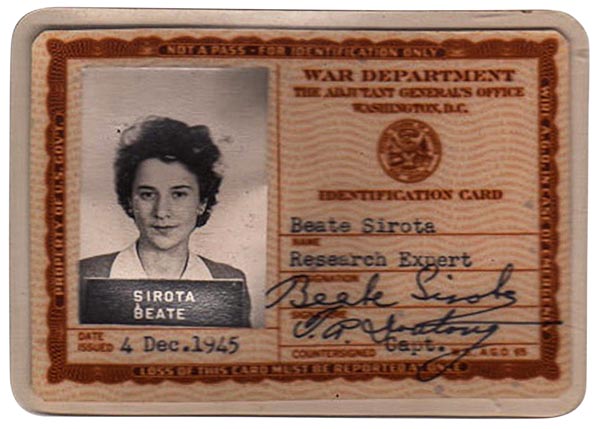

Beate Sirota (later Gordon) was the first non-Japanese civilian woman to enter Japan after the end of the war, arriving on Christmas Eve 1945 to work for the Occupation. The Austrian-born Sirota had grown up in Japan and been stranded in the U.S., where she was attending university, when Japan attacked Hawaii in 1941. Fluent in six languages, including Japanese, after the war she readily got a job with the Occupation that enabled her to be reunited with her parents in Japan.

Less than six weeks after her return to Japan, Gordon was assigned to work on drafting civil rights provisions for Japan’s new constitution. Her teammates on the project suggested that since she was a woman, she should draft the women’s rights section.

Speaking at the FCCJ in 1995, Gordon described her work on that project in early February 1946. To aid her efforts, she borrowed around 10 national constitutions from several local libraries still standing in bombed-out Tokyo and found six, mostly written in the early 20th century, that included provisions relating to women’s rights.

Having grown up in Japan, Gordon understood well the pre-war position of Japanese women. The pre-war Japanese Civil Code stipulated that “women are to be regarded as incompetent”. They could not sue, they could not seek divorce (although their husbands could divorce them), they could not own property. Pre-war Japanese women were powerless, in law and in effect. They were no more than chattels, belonging first to their fathers and later to their husbands.

1 A description of Gordon given by Col. Charles Kades (1906-1996),

chief of GHQ’s Government Section, in an interview for the 1992 Pacific Century documentary series.

Beate Sirota’s 1946 draft civil rights provisions

for the Japanese constitution

III. Specific Rights and Opportunities

18. The family is the basis of human society and its traditions for good or evil permeate the nation. Hence marriage and the family are protected by law, and it is hereby ordained that they shall rest upon the undisputed legal and social equality of both sexes, upon mutual consent instead of parental coercion, and upon cooperation instead of male domination. Laws contrary to these principles shall be abolished, and replaced by others viewing choice of spouse, property rights, inheritance, choice of domicile, divorce and other matters pertaining to marriage and the family from the standpoint of individual dignity and the essential equality of the sexes.

19. Expectant and nursing mothers shall have the protection of the States, and such public assistance as they may need, whether married or not. Illegitimate children shall not suffer legal prejudice but shall be granted the same rights and opportunities for their physical, intellectual and social development as legitimate children.

20. No child shall be adopted into any family without the explicit consent of both husband and wife if both are alive, nor shall any adopted child receive preferred treatment to the disadvantage of other members of the family. The rights of primogeniture are hereby abolished.

21. Every child shall be given equal opportunity for individual development, regardless of the conditions of its birth. To that end free, universal and compulsory education shall be provided through public elementary schools, lasting eight years. Secondary and higher education shall be provided free for all qualified students who desire it. School supplies shall be free. State aid may be given to deserving students who need it.

22. Private educational institutions may operate insofar as their standards for curricula, equipment, and the scientific training of their teachers do not fall below those of public institutions as determined by the State.

23. All schools, public or private, shall consistently stress the principles of democracy, freedom, equality, justice and social obligation; they shall emphasize the paramount importance of peaceful progress, and always insist upon the observance of truth and scientific knowledge and research in the content of their teaching.

24. The children of the nation, whether in public or private schools shall be granted free medical, dental and optical aid. They shall be given proper rest and recreation, and physical exercise suitable to their development.

25. There shall be no full-time employment of children and young people of school age for wage-earning purposes, and they shall be protected from exploitation in any form. The standards set by the International Labor Office and the United Nations Organization shall be observed as minimum requirements in Japan.

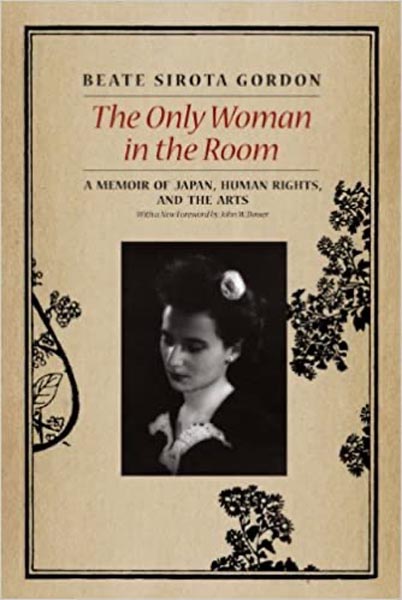

Beate Sirota Gordon’s memoir, University of Chicago Press, US (2014).

In her 1997 memoir, The Only Woman in the Room, Gordon wrote, “I tried to imagine the kinds of changes that would most benefit Japanese women.” She determined that the essentials were “equality in regard to property rights, inheritance, education and employment; suffrage; public assistance for expectant and nursing mothers as needed...; free hospital care; and marriage with a man of her choice.”

Gordon understood Japanese society and traditional male attitudes well enough to know that slipping broad aspirational provisions into the Constitution would not in itself be sufficient to drive the cause of equality for women. She saw that the only way to achieve equal rights for women was to include very specific and insurmountable provisions in the Constitution. In her research, she found similar provisions in the 1918 Soviet Constitution and, in particular, the 1919 Weimar Constitution, which she drew on heavily for her draft entries.

In the end, Gordon wrote eight very specific civil rights provisions for inclusion in the new constitution (see inset). But when her draft came before the Steering Committee, made up largely of American military men, it met with considerable opposition. The Steering Committee objected on the grounds that Gordon’s provisions were too specific and constituted revisions far in excess of the rights enshrined in the U.S. Constitution. As Gordon noted in her speech at the FCCJ, this was not difficult, for “the American Constitution doesn’t even contain the word ‘woman’.”

The Steering Committee maintained that such specificity should be left for inclusion in other laws, like the Civil Code. Gordon tried to push back, explaining to the Committee that, given entrenched male attitudes, the provisions would never make it into law if they weren’t included in the new Constitution from the outset. She admits that she even cried, but the men were unmoved. In the end, the main rights she advocated were included, in an abbreviated form, but the binding details Gordon had wanted were omitted:

Article 24. Marriage shall be based only on the mutual consent of both sexes and it shall be maintained through mutual cooperation with the equal rights of husband and wife as a basis.

With regard to choice of spouse, property rights, inheritance, choice of domicile, divorce and other matters pertaining to marriage and the family, laws shall be enacted from the standpoint of individual dignity and the essential equality of the sexes.

Article 25. All people shall have the right to maintain the minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living. In all spheres of life, the State shall use its endeavors for the promotion and extension of social welfare and security, and of public health.

Article 26. All people shall have the right to receive an equal education correspondent to their ability, as provided by law.

All people shall be obligated to have all boys and girls under their protection receive ordinary education as provided for by law. Such compulsory education shall be free.

If American men on the Steering Committee found Gordon’s ideas hard to accept, the reactions of their Japanese counterparts at a meeting held a month later were off the scale.

Gordon was only attending the meeting to act as interpreter. By her own account, the Japanese liked Gordon as a fast and accurate interpreter, though they had no idea she had been involved in drafting the document under discussion. After several hours of debates over the draft, the group finally reached draft Article 24. The Japanese delegates were vehement in their rejection. For the American Committee, Colonel Charles Kades said, “Gentlemen, Miss Sirota has her heart set on these provisions. Why don’t we pass them?” Stunned by this interjection, the Japanese acquiesced.

In the fullness of time, it is plain to see that the watered-down version of Gordon’s draft has not had the effect she had hoped for. Gordon’s specific, but rejected provisions, which her American colleagues had assured her would enter Japan’s Civil Code, never quite made it.

In her memoir, Gordon wrote: “To this day, I believe that the Americans responsible for the final version of the draft of the new constitution inflicted a great loss on Japanese women.”

Beate Sirota Gordon (centre, facing) with SCAP staffers and others ca.1946

Beate Sirota Gordon, interviewed in later life

Worldly effects

On paper, women were accorded basic rights in the 1947 Constitution. In practice, not much changed outside of voter participation, which pre-dated the new Constitution and over 73 years has remained 60-70%. The Japanese patriarchy continued to resist equality for women as effectively as it had been doing since the late 19th century, when Japanese women themselves first began agitating for social reforms. This validates the characterization of the Constitution as an heirloom sword in the tokonoma, a treasure on display for all to see but not to be used except in the most dire of emergencies.

During the 1950s and 60s, as Japan’s economy recovered and expanded and Japanese society increasingly urbanized, the preferred mythology of Japanese society was a kind of “separate but equal” situation for men and women. There was the so-called “ideology of the male breadwinner” that, these days, contributes to Japan’s reduced marriage rates and the notion that women should stay at home, manage the household, and make babies. Both of these have been highly influential over the past seven decades, although attitudes are gradually changing.

Speaking in 1995, Gordon told the FCCJ:

“Although the basis of women’s rights is there, they have not yet achieved its realization. It’s still going to take a lot of time.” Time has proven Gordon correct.

It wasn’t until 1985 that Japan adopted the Equal Employment Opportunity Law and it did so only to comply with its international obligations under the U.N. Convention for the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women. The new law was as vehemently opposed by the Japanese business community as the women’s rights provisions in the constitution had been by Japanese politicians back in 1946, with the result that in its first decade the law contained no sanctions for breaches. Equal employment opportunity has slowly gained traction but even today gender-biased hiring and promotion continues unchecked.

More recently, the Abe administration has claimed to advocate for increased female participation in both business and political leadership, but even this government intervention has yet to produce significant change. True, women are increasingly achieving leadership roles in business, but numbers are still low and the rate of change is far slower than in most industrialized nations. Participation rates in national politics remain at an abysmal level.

In her 1995 speech at the FCCJ, Gordon’s final advice to Japanese women was to join support organizations, band together, and keep making a noise demanding equality. Twenty-five years on from this advice, movements and campaigns for reform are gaining traction as Japanese women learn to speak out. This is not a uniformly progressive development; it’s still two steps forward and one step back as outspoken women all too frequently find themselves badgered and bullied. But it’s undeniable that the pace of change has accelerated and points forward. Who knows? Maybe we’ll even see a female prime minister by the centenary of women’s suffrage in Japan.

● Vicki L. Beyer is a travel writer, a kanji on the 2020 FCCJ Board, and a professor in the Hitotsubashi University Graduate School of Law Business Law Department.