Issue:

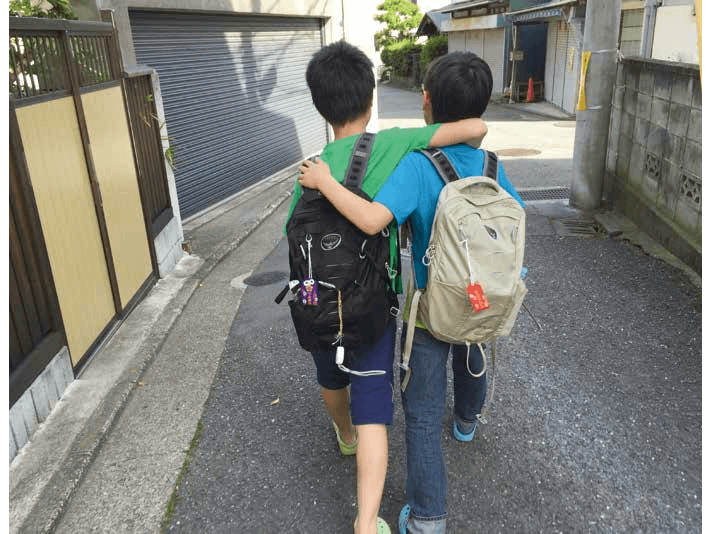

My two (fo ster) sons

A volunteer parent experiences the joys and struggles of expanding children’s horizons and building a family.

by CAROLINE PARSONS

One photo is of a 5 year old boy, beyond cute in a blue plastic rain jacket, singing at a festival in his children’s home. Another captures the big gentle eyes of his younger brother out on a country walk with me, wearing the orange dinosaur T-shirt I had just given him. They are prize possessions, some of the first pictures I ever took of my foster sons.

Eight years ago I started to foster these two Japanese children, turning me overnight into a mother a foster one, anyway. Having children was something I’d always assumed I would do when it felt right. But my Japanese husband and I, both professional photographers, prioritized work, and watched as our thirties passed into our forties. We had four lovely cats but no children of our own.

Eventually I did feel ready. I had hopes that we could grow our family, even if we had to help nature along. But my husband was more determined than ever to live from his art with no day job and feared the resentment that he might feel with the demands of a larger family. So we made the hard decision to support each other’s dreams and divorced. He moved to Europe. I chose to stay in Japan, juggling the fortunes of life as a foreign photographer while putting out feelers to see if there were children who might want what I had to offer: a heart very ready to love a child.

Divorce, single parenthood, adoption, step parents, step siblings and half siblings. I had experienced all of this while growing up in the 1960s and ’70s in the UK, and it was all perfectly normal. So even though my dream of starting my own family was beginning to look seriously challenged by the realities of aging, I knew there were many kinds of families and refused to believe that I could not, should not or would not have children. I did recognize, however, that giving birth to the mother I felt strongly growing inside me might require a fair bit of flexible thinking.

AN AMERICAN FRIEND OF a friend in Tokyo was in the process of adopting a Japanese baby. We’d never met, but she generously chatted to me on the phone between bottle feeds. She knew how I felt and I could feel for her too as she described being on tenterhooks for the next six months, AN AMERICAN FRIEND OF a friend in Tokyo was in the process of adopting a Japanese baby. We’d never met, but she generously chatted to me on the phone between bottle feeds. She knew how I felt and I could feel for her too as she described being on tenterhooks for the next six months, were caring for a baby who might not become theirs and they were having to keep cool, despite being on an emotional roller coaster.

I learned that adoption of children unrelated to you by blood was rare in Japan, but it did exist. The woman’s advice was that I build personal connections with people involved in childcare. I should let them get to know and trust me, and stay patient and open to the process.

I had all that in mind when I visited my local ward office looking for advice on local adoption agencies. They had no such list, but on the desk was a pamphlet about a child fostering seminar that was taking place the very next day. When they saw that I was curious, the staff urged me to go along.

That was in 2008. Now it’s a glorious May morning in 2016. As I write this, my foster sons, two brothers a year apart in age, are indulging in their favorite Sunday morning pastime: a long lie in. I gaze at their sleeping faces as angelic to me today as they were when they first turned “My Home” into “Our Home.”

NOW 12 AND 13, they have lived in a children’s home since they were 2 and 3, when their birth parents experienced intractable difficulties that made them unable to care for the toddlers. Altogether, we spend about two to three months of the year together, including regular weekends and the school holidays. We are a happy trio and, as I believe any parent does, I organize my life around them.

Only about 15 percent find homes with foster families and only a tiny number get adopted. The majority live their whole childhood in institutions.

I’m not suggesting this is an easy journey. It has challenged me to the core every step of the way. Emotionally (the younger brother could be enormously challenging at the beginning), physically, financially, it has taken all I’ve got and more. I still approach things a day at a time and just continue to pray that we will all work out fine. I am heartened that the more time passes, the more closely and naturally we three seem to have bonded in an amazing, organic kind of process.

The number of children taken into care in Japan is increasing every year: there are currently over 36,000 such children nationwide. In the majority of cases, this is due to parental abuse or neglect. Economic hardship, of course, is a big factor.

Only about 15 percent of these children find homes with foster families and only a tiny number get adopted. The majority live their whole childhood in institutions. That figure is very different from the figures in Western countries. In the UK, some 75 percent of “looked after children” are in foster care and in Australia the figure is over 90 percent.

Many studies have been done showing the negative effects of growing up in institutions, how many children will later have difficulty integrating into society as adults. Two years ago, the international NGO Human Rights Watch put out a damning report titled “Without Dreams,” criticizing Japan for being predisposed to institutionalizing children rather than placing them in adoption or foster care. The report claimed these children were being deprived of the family based care that is so important for their development and wellbeing. It urged Japan to be “consistent with its international legal obligations” and to “prioritize the best interests of the child” by phasing out institutions.

I AM A “VOLUNTEER Family” foster parent. Our role is to give the children an experience of life in a family, so we take children growing up in an institution into our homes for weekends and/or the holidays. There are only a few of us doing this and most only take the children for a few days of the year. Most foster parents are Japanese married couples, but the law does not stipulate nationality or marital status and I was accepted into the system, the only foreigner doing this in my area.

If the boys were to live with me full time, which is theoretically possible, I would receive much more training than I did. And I would have full financial support from the child welfare authorities. Last year we discussed this, but the staff involved in the decision were worried that if things went wrong untold damage would be done to our relationship. They have witnessed “families” being crushed under the strain of suddenly living together full time, and asked me to continue as I have been.

One big problem is that there is little financial support in this category. “Volunteer Family” foster parents receive a small daily allowance when the children visit, but it does not cover much more than the cost of transport to and from the children’s home. For the eight years I have been fostering the boys, I have borne the lion’s share of the expenses myself, with help from my family in the UK and friends.

THE BOYS WANT TO come and stay as often as possible and of course I want that too. The more time we spend together, the more we truly do feel like family. But as they’ve grown, so have all the costs food, transport, books and entrance tickets if we go out somewhere. As I currently earn only a modest salary as a children’s teacher, I am now looking for grants and other financial assistance to enable me to support the boys through university.

Fostering a child in the UK would have been an entirely different experience since the system there is far more developed, with a lot of training and financial support. But Japan is where I live so this has been my sole experience with fostering.

I have been warmly welcomed by everyone I have worked with the caseworkers, the psychiatrists (my foster sons are each assigned one and meet with them at regular intervals), the coordinators, the special needs teachers at school. The institution’s teachers are very dedicated, and I know that if I run into trouble when the boys are with me, I can call and ask for help.

Noriko Yamauchi, who is in charge of coordinating with foster parents at the Yokosuka child consultation center, says the government recognizes the problems with institutions, and is working to expand the fostering system. But the target is far from ambitious, calling for only 30 percent of children in care to be placed with foster parents by 2030. While not phasing out institutions, Yamauchi said, they are working to reform them, making them closer to a family environment: group homes in which four or five children live with a male and female teacher.

My foster sons have woken up from their lie in. I told them what I was writing and asked if they had anything to say. The older one said: “Well, when I come here, I have a proper parent and I can enjoy my life because of that.” “I’ve lived in a children’s home since I was little, so I’m used to it,” said his younger brother. “But when I come here, I feel free.”

And our family journey continues.

Caroline Parsons is a retired photojournalist. For more on the foster parent experience, visit her website, friendsoftheboys.org