Issue:

One of the FCCJ’s oldest members has struck bestselling gold with a revisionist book on the “victor’s justice” of WWII. The No. 1 Shimbun talks to Henry Scott Stokes

the FCCJ alumni boasts its share of bestselling authors: Robert Whiting, Bill Emmott and Karel Van Wolferen top the veteran’s list; Jake Adelstein and Richard Lloyd Parry lead the newer pack. You may, however, have missed the latest addition to this select group: Henry Scott Stokes.

A former bureau chief of the Big Three English language newspapers the Times, New York Times and Financial Times, Henry’s Japanese-only book Eikokujin Kisha Ga Mita Rengokoku Sensho Shikan no Kyomou (“Falsehoods of the Allied Nations’ Victorious View of History, as Seen by a British Journalist”) has sold over 70,000 copies since being released last Fall.

“It has just exploded,” says a smiling Scott Stokes in an interview at the Club. “It’s selling 10,000 copies per week.” That means it’s likely that by the time you read this interview the book will have passed the 100,000 mark and may end up shifting a lot more copies than that. “All of which is very flattering,” he admits.

BOOKSTORE BONANZA

Henry’s success is part of a boom in revisionist tomes about Japan’s 1933-1945 long war and the U.S.-brokered postwar settlement that created the nation’s modern education and defense charters. Nationalist-tinged books attempting to overturn the war’s entire narrative can now be found stacked in special displays in many bookstores.

The nation’s Revisionist-in-Chief is Naoki Hyakuta, a fiction writer who has sold millions of books aimed at restoring Japanese “pride.” Hyakuta’s latest, Kaizoku to Yobareta Otoko (“The Man who was Called a Pirate”) an historical novel based on the Idemitsu petroleum company’s court battle with a British oil concern has sold over 1.3 million copies. The big screen adaption of his bestselling debut Eien no Zero (“Eternal Zero”), a sympathetic look at kamikaze pilots, is one of Japan’s top 10 most successful movies ever.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has made public comments suggesting he is a fan of Hyakuta’s oeuvre. Last year Abe triggered controversy by supporting Hyakuta’s appointment as one of 12 governors to NHK’s board,along with several other radical conservatives. Hyakuta subsequently embarrassed Japan’s state broadcaster by saying the 1937 Nanjing Massacre never happened.

This background of increasingly unabashed revisionist posturing is important, says Henry. “This book could not have been published two or three years ago,” he insists. “It has flourished in an atmosphere where the political miasma is totally differ-ent to what I’ve ever seen before. We truly have this sense of change and we felt that Abe was part of this.”

‘IT IS LARGELY AS A RESULT OF JAPANESE SHEDDING THEIR BLOOD THAT WE ENTERED A NEW WORLD WHERE COLONIES DID NOT EXIST’

MISHIMA’S BIOGRAPHER

Henry describes himself as politically “right of center.” He once wrote a book on Japan’s most famous radical right-winger, The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima (1974), and he returns to Mishima in the new book as something of a lay prophet. He says he has come to agree with Abe on Yasukuni Shrine and likes the “cheerfulness and spunkiness” of the prime minister. “I find myself talking the same language. [Abe] says ‘What about Arlington?’ The Americans are entitled to have a place to grieve. Why shouldn’t the Japanese?”

His essay-style book interrogates the “victor’s justice” of the Tokyo war crimes trials and explores Henry’s thesis that the U.S., not Japan, bears what he calls “prime responsibility” for the Pacific War. The raising of the Stars and Stripes aboard the USS Missouri on September 2, 1945 was the culmination of America’s attempt, which had been ongoing since the arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry, to bring Japan to heel, he says.

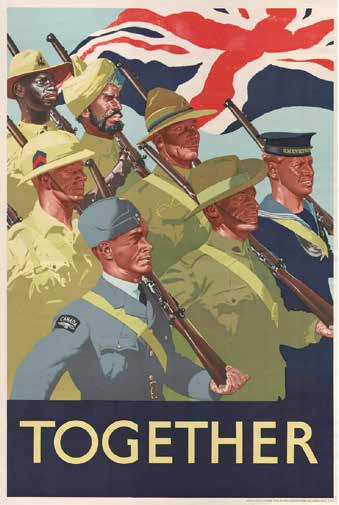

Henry sides with the staunchest revisionists in attributing the end of European colonialism in Asia to imperial Japan “Asia’s light of hope,” he says. “It is largely as a result of Japanese shedding their blood that we entered a new world where colonies did not exist any more and there is racial equality.” The tone of the book is set in Chapter Two, which rhetorically asks: “Is Japan the only criminal country?”

AUTHORSHIP RESPONSIBILITY

Oddly, perhaps, he admits to not knowing exactly what’s between the pages of the book that carries his name he says he reads little Japanese and an English translation has yet to be produced. It was dictated over hundreds of hours to another FCCJ member, Hiroyuki Fujita, then brought to publication by Tony Kase, an old friend of Henry’s with connections to the LDP. “Tony Kase had the most to do with this,” he explains, but adds: “I have to accept responsibility for it since it is in my name.”

The book was triggered by Henry’s desire to describe how Japan is changing in a way that he finds unique in his half a century in the country. “When I first came here, the universities of this country were a sea of posters for the left wing. Everyone was left wing except for Yukio Mishima. We don’t have those anymore. Everyone is on the right, or right of center.”

He says Yasukuni is key to understanding this changing collective psyche. “Right now, the rest of the world is lined up against the Japanese. Any other time, the Japanese public would have got frenetic about this, about being isolated.” This time, however, the controversy hasn’t led to “hysterical overreactions.” “There has been a sort of calmness and maturity.”

During the interview, Henry does not tread Hyakuta’s controversial path of denying Nanjing, though he does say the event is “unknowable in many aspects.” “The stance I take is that ghastly events occurred in Nanjing,” he explains. “Responsibility lies with the Japanese military, Chinese military and Chinese Communist Party. And to know the details of what happened is largely impossible.”

The book’s argument is balder. Chapter Five is titled “The massacre that even (former Chinese leader) Mao Zedong and (nationalist rival) Chaing Kai-shek denied.” The chapter argues that there is no proof for the massacre of 300,000 people by the Japanese Imperial Army, as Beijing claims.

“I have never found myself driven into a corner and denied that anything happened,” Henry responds. “You have to say that the homework on Nanjing hasn’t been done yet. The debate and the wrangling over how many people died is terribly badly done. It is a work in progress that has only just started.”

On comfort women, the war crime issue du jour, Henry says he finds “convincing” the arguments of Osaka Mayor Toru Hashimoto, who triggered a furor last year by saying there was no evidence of Japanese state involvement in herding Asian women into military brothels. “I’ve been seated on the stool [about this issue] for too long,” says Henry. “Why don’t I get off?”

ADVICE FOR OSAKA MAYOR HASHIMOTO

Again, the book is much less ambiguous. Chapter Four says the comfort women were high-class prostitutes, paid far better than the soldiers who “exploited” them ¥300 a month to the ¥10 of an average grunt. America, it says, has a history of slaves; Japan does not, partly explaining the lack of understanding on the issue. “In America and Europe, women in wartime have always been targeted, raped and hurt in history,” it says, in comments that echo Hashimoto’s.

Hashimoto defended his views at a marathon FCCJ press conference a year ago, but Henry thinks he should not have come. “He was surrounded by a hostile audience.” Instead, the embattled mayor should have called his Tokyo presser at a hotel where he would have been surrounded by an army of like-minded supporters, says Henry.

Over a long career, Henry has interviewed many of the architects of Japan’s flourishing neo-conservatism, including Abe’s grandfather, Nobusuke Kishi and his father, Shintaro, who served as foreign minister in the LDP.

He was born into a Quaker family and dodged a career at the family shoe business in England before talking his way into a job at the Financial Times, initially covering commodities. One of his odder near career misses was a failed consortium with comedian Peter Cook to buy the satirical magazine Private Eye. But he says he quickly tired of the snobbishness and elitism of London. Eventually, he landed a foreign correspondent job, arriving in Japan first in 1964.

It was the beginning of a lifelong love affair, both with Japan and writing. “I just wanted to shine and be glorious in my own way,” he says. For better or worse, this book may be his legacy.

David McNeill writes for The Independent, The Economist, The Chronicle of Higher Education and other publications.