Issue:

June 2022

FCCJ Freedom of the Press Awards recognise bravery of Hong Kong, Russian journalists

It will come as no surprise to readers of the Number1 Shimbun that authoritarian governments are waging a war on journalists, and that press freedom is declining across much of the world. The 2022 World Press Freedom Index, compiled by Reporters Without Borders (RWB), says the media are in a “very bad” situation in a record 28 out of 180 countries. It singles out Russia (155th), China (175th) and hardly perennial North Korea (180th). Alarmingly, the index warns that even in the rich West, social divisions are growing “because of the disastrous effects of information chaos” and unregulated online platforms “that encourage fake news and propaganda”.

It is surely an appropriate time, then, to celebrate press freedom and commemorate the work of journalists under siege. The annual FCCJ Freedom of the Press (FoP) Awards on April 26 recognized the remarkable domestic careers of Shigenori Kanehira, one of the few senior Japanese reporters to make a reporting trip to wartorn Ukraine, and Soichiro Tahara (Lifetime Achievement Award), a liberal reporting icon still going strong at 88. But even they would have agreed that alarm bells for the media in our corner of the world are ringing loudest in Russia and China, and it was there that the awards devoted most of their attention.

"The Freedom of the Press Award is a landmark in our activities and has been since FCCJ was launched in 1945," FCCJ President Suvendrini Kakuchi said at the ceremony. Reminding everyone that Japan's postwar constitution guarantees press freedom and freedom of expression, she noted: "Of course, the interpretation of democracy is what our awards single out."

This year’s Asia Award went to journalists in Hong Kong, once a bastion of press freedom, but no longer. China’s crushing of the media and civil society has sent Hong Kong’s RWB rating plummeting from 18th place in 2002 to 148th in 2022. Attacks have come thick and fast in the last year: In June 2021, Hong Kong’s chief executive, Carrie Lam, used the National Security Law as pretext to shut down Apple Daily, the territory’s largest Chinese-language opposition newspaper, and to prosecute at least 12 journalists and press freedom defenders, including its founder Jimmy Lai, who is facing a possible life sentence. In December, independent media Stand News announced it has shut down following the arrest of six current and former members of its team.

A day earlier, the FCCJ's sister organization, The Foreign Correspondents' Club of Hong Kong, had to suspend its annual Human Rights Press Awards this year due to concerns it might violate the law.

Accepting the prize, Ronson Chan, chair of the Hong Kong Journalist Association – who has himself been detained by police – quoted 2021 Nobel Peace Prize winner Maria Ressa. “Without facts, you can’t have the truth. Without truth, you can’t have trust. Without trust, we have no shared reality, no democracy, and it becomes impossible to deal with the existential problems of our times: climate, coronavirus, now, the battle for truth.” Chan added: “Yes, we are in a tough environment and journalists may need to sacrifice more to achieve more, but I still believe Hong Kong journalists are willing to serve.”

An Honorable Mention in the Asia Award went to Novaya Gazeta, “the last independent newspaper in Russia”, famously edited by Dmitry Muratov, co-winner of the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize. Speaking via Zoom on behalf of the newspaper, Pavel Kanygin gave an emotional speech, thanking the FCCJ for supporting the global community of journalists in “dark times”. “It helps us feel we are not alone,” he said, adding that the months since Russia invaded Ukraine had been a “nightmare”.

“Those opposing the war became enemies of the state,” he added. “The expression itself – no war – became a crime if spoken loudly in a public setting. A crime that will bring a regular individual to prison for three years, and for 15 years if you are a professional journalist. People are scared not only for themselves but for their loved ones, friends and family members. More and more the regime reminds us of the Stalin dictatorship era when people lived in fear of being prosecuted for jokes, and when snitching on each other became a new societal norm.”

The news wasn’t all bleak, however. A team of former Novaya Gazeta writers has launched a new edition of the paper - Novaya Gazeta in Europe. And Kangyin said that he had helped set up a digital multimedia project called To Be Continued “aiming to reach Russian audiences on YouTube and Telegram - two huge platforms that the Russian regime fears. “We believe that there’s a better future for Russia and its people,” Kangyin said. “We hope that with our help people see the truth.”

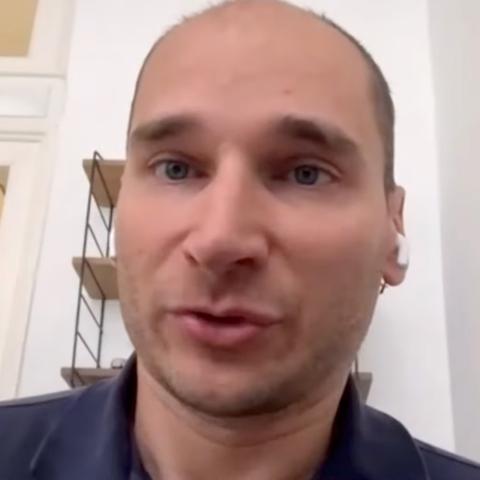

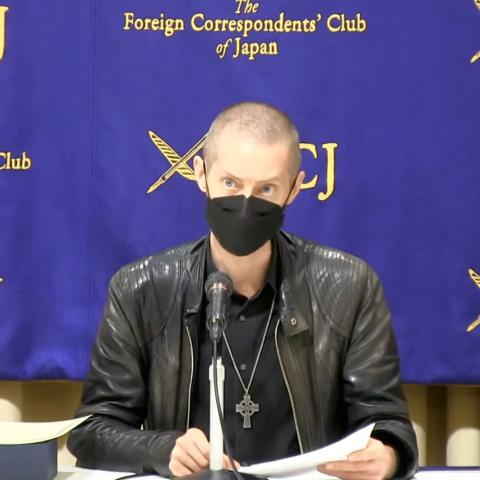

The Japan Award went to Tokyo-based documentary maker Thomas Ash, whose many award-winning documentaries have focused on hard-hitting issues that are often neglected by the mainstream media. His latest work, “Ushiku,” takes viewers deep into the psychological and physical environment inhabited by foreign detainees in one of the largest immigration centres in Japan by the same name. The FoP said that Ash “conveys the inhumanity of the current system and the immense damage it causes to vulnerable immigrants and asylum seekers.”

In a typically self-effacing speech, Ash said that he hoped the award would throw more light on the victims of the immigration system.

“The nine people who represent so many thousands of others who are either indefinitely detained, or who are out on provisional release, without the ability to work, without health insurance, and without freedom of movement," Ash said after dedicating his award to them.

He added: “Article 21 of the Japanese constitution guarantees freedom of speech, press and all other forms of expression. If journalists, activists, and filmmakers had had the freedom to record and share the voices of those in detention, conditions inside these internment camps would never have deteriorated to this extent. In other words, if we had true freedom of speech and true freedom of the press, this film would not have needed to be made.”

David McNeill is professor of communications and English at University of the Sacred Heart, Tokyo, and co-chair of the FCCJ’s Professional Activities Committee. He was previously a correspondent for The Independent, The Economist and The Chronicle of Higher Education.