Issue:

THE STORY BEHIND THE UNRAVELLING OF JAPAN’S MOST CHARISMATIC POLITICIAN

October 22, 1974 was a seminal day for the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan. The consequences of what took place at the press conference held that day still resonate in the halls of the Club many years later.

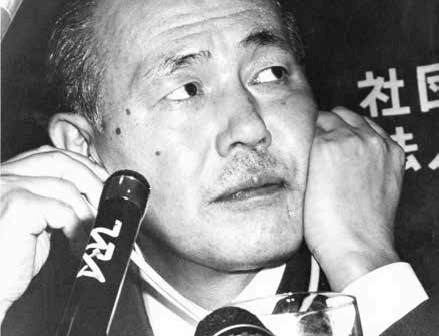

It began with then Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka fulfilling the customary commitment to appear before the foreign correspondents; it ended with Tanaka as the target of increasing calls for investigation into his financial background. There is no lack of analysis into what followed as Tanaka was shaken, then toppled from his perch at the helm of the country but it is rare to have a voice explaining the details of what led up to the historical press conference, and the coincidences that made things happen the way they did.

The late Sam Jameson left this piece, written in 1996, which recounts his own role in his position as prior FCCJ president and facilitator of Tanaka’s appearance. It is a fascinating, inside look at how the Club and its member journalists operated at the time. It is also as much a part of Japan’s history as it is the Club’s.

by Sam Jameson

Day of Reckoning: Kakuei Tanaka and the FCCJ

Although nearly 22 years have passed since the event, somehow the day that Kakuei Tanaka came to the FCCJ still stirs passions among old time Members.

No one has ever written the whole story about what led to that day and what happened on Oct. 22, 1974. And with Tanaka gone, it is too late to put together all the sides of the story.

But as an event that changed the political history of Japan, perhaps one more “blind man feeling the elephant” story is merited. If Tanaka had come to the FCCJ when, by custom, he should have come, it is virtually certain that he would not have been forced to resign. He would have served at least another two years as prime minister; indeed, he might have been in office and forestalled the 1976 U.S. Senate revelations of Lockheed’s secret dealings in Japan.

My role in Tanaka’s appearance at the Club was an accident of history.

I was serving as president at a time when the foreign ministry and the Prime Minister’s Office had agreed by informal consensus that the prime minister should come to the FCCJ once a year, in principle. But by April 1974, or nine months into my term, Tanaka had not come since 1972. I liked Tanaka and wanted him to come while I was still president so that I would have the pleasure of introducing him and hosting the luncheon and I created a chance to ask him to come at the annual prime minister’s cherry blossom party in Shinjuku Garden.

After waiting in the long line of guests, I took the few seconds I had with Tanaka as I shook his hand to say to him in rapid fire Japanese:

“Mr. Prime Minister, you have not come to the FCCJ. Are you afraid of foreign correspondents?”

Tanaka laughed heartily, but said only, “Wakatta! Wakatta!”

Behind him, within hearing distance, was his chief Foreign Ministry secretary, Akitane Kiuchi. I walked around the VIP line to say hello to him and he said he would try to get the PM to come to the Club. I explained to him that I would be president only until the end of June.

I did not have a close association with Tanaka but he and I had met from time to time over a period of about 10 years. He was a personality who left a strong impression on anyone who met him.

In an exclusive interview with him when he was secretary general of the LDP in the late 1960s, I asked him on what conditions he thought Japan ought to seek the reversion of Okinawa.

“The return of Okinawa administration rights is one kind of transaction. In transactions, there is a seller and there is a buyer. First, the seller sets the price, and then the buyer decides whether to make the purchase or not,” he replied.

Initially, I was shocked. How could a leader of a country talk about seeking return of part of his nation’s territory in the terminology of a horse trader?

Later, I came to see that in that reply to my question, Tanaka had summed up what appeared to be his basic philosophy: namely, that politics is always a transaction (torihiki). And as long as no bribes are involved, that isn’t a bad definition for the way a democracy should work in any country.

I was privileged to know Tanaka well enough before scandals demolished his cheerful personality when he often acted as if he were a simple, open hearted country boy to consider him a leader with an extremely engaging personality.

At Honolulu in August 1972, when he met President Nixon prior to going to Beijing, I sat next to Tanaka for about 10 minutes during a garden party at the home of the Japanese consul general.

ELIAS’ SPEECH WAS ONE LONG, ENDLESS, PAINFUL SERIES OF JABS, SOME BORDERING ON INSULTS

“I told President Nixon he shouldn’t worry about the trade deficit. Japan is such a close ally of the United States that it’s like putting all of that money in one purse. But Nixon wasn’t convinced,” Tanaka said, laughing heartily.

In a display of friendly accessibility that I have never seen any other leader of a country make toward reporters, Tanaka chatted with every reporter in the traveling press group.

As he was about to leave Haneda Airport in September 1972 to establish diplomatic relations with the Beijing government, Tanaka headed for his airplane walking on a red carpet and shaking hands with VIPs. I was standing at least five meters behind the VIP line but when Tanaka came abreast of me, he pushed aside two of the VIPs and walked forward.

I was too flabbergasted to move, and he walked all the way over to shake my hand. All I could say was, “Pl pl pl please go and return safely.”

It was the same kind of charm Tanaka always displayed toward his supporters in Niigata 3-ku, whose names and whose children he remembered unfailingly. As a reporter, I knew I shouldn’t let such a display sway me. But that act and the other kindnesses Tanaka showed over the years did sway me. I liked him. And if he had come to the FCCJ while I was still president, I would have given him a friendly introduction.

But, as it turned out, the vagaries of scheduling prevented an appearance before June 30 [the end of Jameson’s term]. Finally, the summer was drawing to an end, as Kiuchi contacted me about Tanaka appearing at the Club. I suggested that the two overseas trips Tanaka was planning for the fall might provide an opportunity for a luncheon. The appearance was scheduled between the two trips.

Only after the date was fixed did the Bungei Shunju “Kinmyaku” article about the torihiki of Tanaka over his entire career appear. No move was made to change the date. But an official in the press section of the foreign ministry called me to ask what questions I thought Tanaka might be asked. I replied that if Tanaka had not made any statement about the Bungei Shunju article by the time he came to the Club, that he would be asked about the kinmyaku charges.

Thus, it is certain that the Foreign Ministry and Tanaka knew in advance that he would face at least one kinmyaku question.

What neither the Foreign Ministry, nor Tanaka, nor members of the Club expected, however, was the introductory speech delivered by Bela Elias, the Tokyo corre spondent of the communist Hungarian News Agency.

Elias was an extraordinarily cheerful person with what usually was a good sense of humor. I had appointed him to the board of directors of the Club when another board member left Japan and had to resign.

As if all the elements of fate were working against Tanaka, Max Desfor, my successor as president, was out of town, so Elias filled in for him as the MC at the Tanaka luncheon. Desfor was a pleasant man but had no sense of humor and if he had delivered the introductory speech, it would not have been the disaster that Elias made it.

Elias, in fact, asked for my opinion about whether humor would be appropriate for an introduction to the PM. Assuming (as it turned out, incorrectly) that Elias would balance any humorous pokes at the PM with an equal amount of praise, I assured him that it would be acceptable.That advice turned out to be a horrible mistake.

Elias’ speech was one long, endless, painful series of jabs, some bordering on insults with no balancing praise at all. I cringed as he delivered it, and later that day called Kiuchi to apologize.

Tanaka scowled at the speech but made no overt protest. Two reporters asked him questions that had nothing to do with kinmyaku, and then I got up to question him.

Because the venue was the FCCJ, I asked the question in English. But I made it a point to look him in the eyes to show that I was not being nasty. And I intentionally put the question in an international context, citing investigations that the U.S. Congress was making at that time into the financial affairs of vice presidential nominee Nelson Rockefeller. I asked Tanaka if he thought investigations into the financial affairs of a politician were appropriate, and asked him to comment on the charges in the Bungei Shunju article.

Tanaka looked me in the eyes when he replied, and did not appear angry as he spoke. And if his reply had been a straightfor ward denial, it all might have ended right there. But his answer was vague, stirring another correspondent to follow up with another kinmyaku question. Two more questions followed and Kiuchi gestured to Tanaka to leave.

Complaining about “excessive questions about a magazine article,” Tanaka and his party walked out.

Tanaka’s answers were so vague that trying to write a story about what he said about kinmyaku was all but impossible. The real news, as it turned out, was yet to be made and that was the news that was created by the Japanese media.

The large national dailies had not been reporting anything about the Bungei Shunju article or kinmyaku scandals. But all of them leaped on Elias’ introduction and the four kinmyaku questions as an excuse to pull the scandal in from the “cold” of weekly Japanese journalism, which is always ignored by the mainstream media.

Detailed reports of the introduction and full transcripts of the Q&A were printed to give the impression to Japanese readers that kinmyaku had become an issue of major international importance and, by implication cause to drive Tanaka out of office.

As popular as Tanaka had been at the beginning of his term, when he was about to realize the dreams of the Japanese media to establish diplomatic relations with Beijing, by this time two years later the simple country boy with a 10th grade education from night school had worn out his media welcome. [Tanaka resigned on Nov. 26 after LDP rivals began a public inquiry in the Diet.]

When I asked the first question, I thought I was merely asking for a comment on a subject that Tanaka had not yet discussed. I was astonished and remain so by the campaign against him that the Japanese media launched, using the Club appearance as an excuse.

As events showed, it was not a campaign against corruption. It was a vendetta against an individual politician whom the press had simply grown to dislike, at least partly because of his humble upbringing. After Tanaka had been driven from office, the word “kinmyaku” and all the whiffs of charges against him, disappeared from the media until Lockheed emerged in the U.S. in 1976.

Japanese leaders, like then Construction Minister Takeo Kimura, speculated in public that American correspondents had “plotted” to get rid of Tanaka. To me, a correspondent who believes, even today, that Tanaka was one of the best Japanese prime ministers from an American standpoint, such an accusation was preposterous. (Tanaka solved in one year nearly all of the economic complaints Americans accumulated against Japan during the seven years and eight months of “the politics of waiting” of Prime Minister Eisaku Sato.)

The truth is closer to the criticism made by political commentator Minoru Morita. He commented that the Japanese press suffers an intellectual “menstruation” (gekkei) once every 10 years or so, and needs to go on a witch hunt against a politician.

Tanaka was the victim of the 1970s. But that is just one blindman’s portion of the elephant.

IT WAS A VENDETTA AGAINST AN INDIVIDUAL POLITICIAN WHOM THE PRESS HAD SIMPLY GROWN TO DISLIKE.

Excerpts from the transcript of Bela Elias’ introduction of Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka (at the FCCJ, October 22, 1974)

“If you want to know everything about his family life, please read Newsweek. As to his personal well being or financial affairs, you can probably find more than enough in the latest issue of Bungei Shunju (boisterous laughter).”

“He’s a man of great contrasts. He has a deep sense of informality, humor and compassion, or at least I hope so (laughter).”

“. . . he has his likes and dislikes . . . they say he dislikes Western food, the teacher’s union, and expressions like “inflation” or “shunto.”

“He was born to a humble farming household . . . before he became a businessman, a politician and finally the prime minister of Japan. Witness the phenomenal change of his defeated and devastated country from rags to riches naturally not without any favorable effect upon himself. If one may believe the usually reliable Japanese press, the total interests he controls . . . is more than ¥2 billion.”

“His party’s flying apart, the economy is in depression, inflationary trends and prices skyrocketing not to mention the latest atomu shokku (laughter).”

“In his well publicized book, The Submersion of Japan — gomen nasai (hearty laughter) I wanted to say, Building a New Japan — he proved he is not only a shrewd businessman . . . but a man of noble dreams.”

“The Mainichi Shimbun reports that the popularity of the Tanaka Cabinet has shrunk to a mere 18 percent . . . The horizon for our guest of honor looks definitely gloomy.”

“He says, ‘two thirds of my term as party president has passed. I will throw the ball with all my might during the remaining one year. . . . Let us hope that his ball will not turn out to be a boomerang.”