Issue:

October 2025 | Richard Hughes Part 2 of 3

The life and times of Richard Hughes

This is the second part of an article about the great chronicler of Asia and, briefly, the manager of the FCCJ

As a child, Hughes had been a devoted fan of fictional detective Sherlock Holmes and in 1920 was able to meet Arthur Conan Doyle during his tour of southern Australia. Thanks to a formidable memory, Hughes had an encyclopaedic knowledge of all of the Holmes stories.

Hughes organised a Sherlock Holmes society in Tokyo soon after he had begun working for Ian Fleming. It was called the "Baritsu Chapter" after the "Japanese wrestling" Holmes employed to hurl his arch-enemy Moriarty into the Reichenbach Falls. (Baritsu was a misspelling of bartitsu, a hybrid martial art that flourished in fin-de-siècle London.)

The Baritsu Chapter held its inaugural meeting on 12 October 1948 at the Shibuya residence of Walter Simmons, correspondent of The Chicago Tribune. It was no ordinary recreational club.

Kenichi Yoshida, a literary scholar, read out a learned paper about Holmes and Japanese martial arts that his grandfather, Count Makino Nobukai had composed on his deathbed. Count Makino was a former counsellor to Emperor Hirohito. His son-in-law was then prime minister Shigeru Yoshida, who "pleaded urgent cabinet business and an appointment with General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander" for a last-minute cancellation of his planned attendance.

Hideki Tojo and Sadamichi Hirasawa

George Blewett was one of Hideki Tojo’s defense lawyers at the Tokyo war crimes trial and during the meeting gave a "well-reasoned solution" to the mystery of Tojo’s suicide attempt, while police detective Tamigoro Igii offered a "firsthand inside account of the detection and arrest of the mass murderer, Sadamichi Hirasawa, for the poisoning of sixteen bank employees".

A renowned tempera artist, Hirasawa was sentenced to death for the fatal poisoning of 12 staff of the Teikoku Bank in a January 1948 robbery. A man posing as a public health official visited a Teigin branch in Tokyo, and by claiming it was vaccine against epidemic dysentery, persuaded employees to drink a solution of potassium cyanide.

Hirasawa always protested his innocence, and successive Japanese justice ministers refused to approve his execution. Aged 95, Hirasawa would die of pneumonia in prison hospital in 1987.

Hughes was convinced of Hirasawa’s guilt, as was Al Pinder, who once told me how he had “looked into” the Teigin case during the Occupation and concluded Hirasawa was “guilty as hell”.

Hughes reported on the Baritsu Chapter in an article for the Sunday Times. "Bujitsu in Baker Street," published in February 1950, concluded that Sherlock Holmes had brought "East and West together, irrespective of race, colour and political ideology … The philosophic observer may well speculate on the significance in current international affairs of the continued absence of any branch of the Baker Street Irregulars in Moscow and of the stubborn refusal of Joseph Stalin to read any of the Sherlock Holmes adventures".

On behalf of the Baritsu Chapter, Hughes arranged for a plaque to be installed outside the Criterion Hotel in London’s Piccadilly in 1953. It commemorated the fictional encounter that led to Dr. John Watson’s introduction to Sherlock Holmes. The unveiling was televised by the BBC. Three years later, the plaque was stolen. It later turned up in an empty cupboard of a house in Wimbledon.

In a curious sequel, the Japanese Consulate General in Edinburgh is the last residence of the man who was Conan Doyle’s inspiration for Sherlock Holmes. Dr. Joseph Bell was a pioneer of forensic science, and taught Conan Doyle during his medical studies at Edinburgh University. Bell also took part in the Jack the Ripper police investigation in London.

The Japanese consulate has occupied the building since 1991. It says it was made aware of the connection by journalist Takeshi Shimizu of the Japan Sherlock Holmes Club. On the centenary of Bell’s death, a bronze plaque was unveiled in front of the building.

Finding Burgess and Maclean

Hughes’ biggest scoop was an interview that lasted all of five minutes at the end of a protracted, expensive and otherwise deeply frustrating trip to Moscow.

Ian Fleming had decided that the Sunday Times should "mount a hit-and-run sally into Russia" at the end of 1955. The Twentieth Congress of the Soviet Communist Party was set for the New Year, and Nikita Khruschev, the new paramount leader of the Soviet Union after Stalin’s death in 1953, accompanied by premier Nikolai Bulganin, was expected to bring a charm offensive to Britain. Hughes happened to be in London at the end of his biennial leave and was handed the plum assignment.

Hughes joined a bevy of foreign correspondents in Moscow all chasing an interview with Khrushchev. Imploring letters from Hughes to the head of press at the Soviet Foreign Office were ignored and Khruschev instead granted an exclusive to the world’s biggest-selling newspaper, the News of the World. The London tabloid story ran on 29th January 1956. Hughes cabled his head office "As directed I will retreat from Moscow Sunday 12 February. Despondent regards."

The offer of an interview with foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov, a Stalinist hangover whose days in office were numbered, seemed small consolation.

However, there was an even bigger Russia story that had Fleet Street editors salivating, and that was to find and interview Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean from the ‘Cambridge Spy Ring’ who had vanished after defecting to the Soviet Union in 1951. Their treachery had shaken the British establishment and shattered American confidence in British security. Maclean had worked at the U.K. Foreign Office while Burgess, once described in the Guardian as a "smelly, scruffy, lying, gabby, promiscuous, drunken slob," had swapped roles at MI6, Special Operations Executive, MI5 and lastly at the Foreign Office. Together they had passed thousands of secret documents to the NKVD and its successor, the KGB.

Hughes had nothing to lose and decided to roll the dice. "I decided after the run-around that I had suffered, that politeness was a bourgeois weakness, and that the blunter my representation the greater my chance of a response."

After a downing a cup of vodka, he composed a letter for Molotov to pass on to Bulganin and Khrushchev. It read: "I would strongly urge you to abandon at once your protracted, futile and absurd policy of silence about the two British defectors, Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess … Mr Khrushchev’s continued line of foolish denial makes it clear that your so-called advisers are completely ignorant of the deep and abiding British public interest in the Maclean-Burgess mystery … You would be wise to produce Burgess and Maclean with some sort of agreed explanation of their actions before you leave Moscow … I leave Moscow on Sunday week, 12th. If you agree, Maclean and Burgess should make their appearance on Saturday, February 11, and the deadline that day for my newspaper, The Sunday Times, should be, say, 5 pm."

Hughes stayed in his room at the Hotel National all week, "scratching out some dull feature stories," and nursing a tooth abscess "which began to bloat my right cheek to the size of a cricket ball". Saturday arrived, and in the afternoon, he began to finish off a last bottle of vodka. By 5 pm he was distinctly tipsy. He began to pack.

At 7:30 pm the phone rang. “Mr Hoojis, can you please come round to Room 101?” It was the television room. He ignored the summons and kept on packing. The telephone rang again. “Mr Hoojis, please come now. Urgent.”

Inside Room 101 five men were seated around a white-clothed table. Maclean and Burgess stood up and introduced themselves. The other three were Sydney Weiland from Reuters and representatives from Tass and Pravda. Burgess handed out four copies of a signed, typewritten, three-page, thousand-word "Statement by G. Burgess and D. Maclean". Its content was the sort of guff one would expect. It ended: "As a result of living in the U.S.S.R. we both of us are convinced that we were right in doing what we did."

After some small talk, the "interview" was ended. It was then almost 8 p.m. and Hughes sprinted out of the room to fetch typewriter, paper and carbon. When he came back to Room 101, it was empty. Burgess and Maclean had already left the hotel in a limousine.

"The story, of course, wrote itself – as all good stories do. I only skimmed the approved statement and didn’t even file it, telling the office to ‘uppick from Reuters.’ In the curious news trade, what mattered was to have seen and talked with the legendary pair."

The story in the Sunday Times earned Hughes an ecstatic herogram from London.

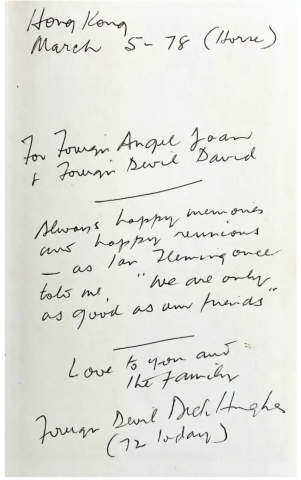

"My expense account showed that the Moscow mission, which lasted seventy-two days and was justified only by the last-minute, five-minute encounter, cost £2,000 [equivalent to £63,800 in today’s money, or ¥12.7 million], plus salary, transport and communication charges. Milord Kemsley slipped me a £1,000 personal cheque – drawn, I noted, on his personal account, not The Sunday Times. I had my fiftieth birthday in Paris and returned to Tokyo to break camp and shift base to Hong Kong."

Hughes had less luck in tracking down the "Third Man" of the Cambridge Spy Ring who had tipped off Burgess and Maclean in 1951.

Kim Philby had joined MI6 in 1940, despite having joined the Communist Party in the 1930s, and just before World War II ended, was appointed head of MI6’s anti-Soviet section. He later became Britian’s chief intelligence officer in the United States. Suspicion fell on Philby in the wake of the disappearance of Burgess and Maclean, and in July 1951 he resigned from MI6. UK foreign secretaries have responsibility for MI6, and then incumbent Harold Macmillan declared Philby to be innocent in 1955. One year later, the editors of The Observer and the Economist were persuaded by friends in MI6 to hire Philby as their Middle East correspondent, on a handsome retainer plus travel and expenses. At the same time, Philby was re-engaged by MI6 as an agent, with an additional retainer to be paid by the chief of the Beirut MI6 station.

It took many years for the net to finally close on Philby’s treachery. Finally, in 1963 he fled at night from Beirut aboard a Soviet freighter

Hughes spotted Maclean at the 1963 funeral in Moscow of dissolute Burgess but there was no sign there of Philby. It would take another larger-than-life Australian journalist to bag an interview with the "Third Man" for the Sunday Times. Murray Sayle, a longtime FCCJ member who died in 2010, gave out two versions of how their encounter occurred. Philby was a lifelong cricket fan and would regularly visit the Central Post Office in Moscow to pick up letters and copies of The Times that published the cricket scores. Sayle would often regaled listeners with the tale of how he staked out the Moscow post office for Philby to show up. A different account came in Sayle’s world exclusive in the Sunday Times of 17 December 1967 – Philby called the Moscow hotel where Sayle was staying and arranged a meeting.

In a review of Robert Whymant’s Sorge biography for the London Review of Books, Sayle wrote how during a "dizzying Moscow fortnight in 1968, Philby and I sampled the mind-expanding powers of Polish vodka, Cuban rum, Georgian wine, Armenian brandy and palate-cleansing Russian beer, with the odd mouthful of borscht to keep us going".

When Sayle asked how he felt being called a traitor, Philby gave the memorable reply, “To betray, you must first belong. I never belonged.”

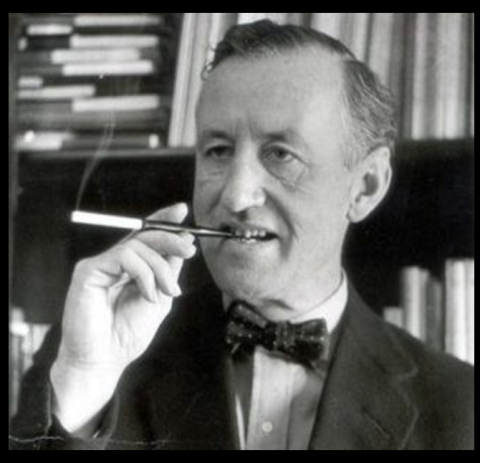

Ian Fleming in Japan

The creator of James Bond twice visited Japan, both times in the company of Hughes and his friend Torei Saito of the Asahi Shimbun.

By 1959, Fleming had become a celebrity author, and the Sunday Times gave him a licence to travel, an all-expenses trip around the world for a series of essays called "Thrilling Cities." He flew out from London in a Comet, the world’s first commercial jet airliner and an apogee of sophistication.

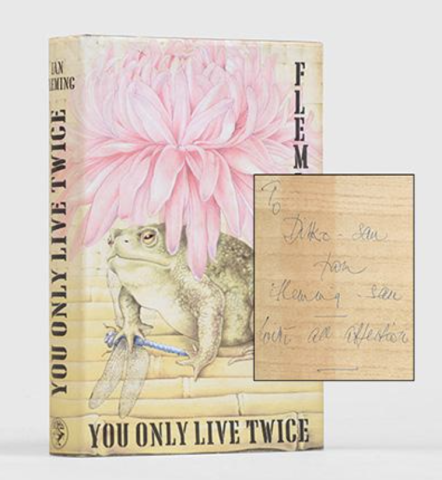

"Dikko," as Fleming called Hughes, was more than "Our Man in the Orient" as Far Eastern correspondent of the Sunday Times. He was "my guide, philosopher and friend", Fleming wrote, "a giant Australian with a European mind and a quixotic view of the world".

"Tiger" Saito is described in Thrilling Cities as a "chunky reserved man with considerable stores of quiet humour and intelligence, and with a subdued but rather tense personality". He had a black belt in judo, and "looked like a fighter," with "a formidable quality about him".

Saito had joined the Asahi after studying architecture at Waseda. He became editor of its new monthly magazine Koku Asahi (Aviation Asahi) in 1941, the year of Pearl Harbor. Later he became an Asahi war correspondent attached to the Imperial Navy. After the war, he edited Kagaku Asahi (Scientific Asahi), became friends with Hughes, and was among the first to join the Baritsu Chapter. In 1953, Saito was given the plum job of chief editor of This is Japan, a lavishly illustrated 300-page annual published by Asahi. Distributed to foreign diplomats and businesses in Japan, and abroad through Japanese embassies to people of influence, it counted many distinguished Japanese and foreigners among its contributors, including Hughes and Fleming.

Fleming’s visit for Thrilling Cities whetted his interest in having his twelfth Bond book set in Japan, and he returned in 1962 on a fourteen-day trip to research what became You Only Live Twice. He entrusted Hughes with the itinerary, who enlisted Saito.

"We travelled by car, steamer, train, hydrofoil, funicular, sedan chair and riverboat, stayed at Western-style hotels and lonely inns, purified ourselves at the Grand Shrines of Ise, crossed the Inland Sea, paid reverence to the great Japanese poet Basho (a sort of poor Oriental’s Shakespeare) at one of his innumerable birthplaces, concentrated on sake, lay long together and argued ideologically in jot -spring baths, survived two mild earthquake shocks, narrowly avoided violence with a group of foreigners in the dining car of the night express from Kyushu to Tokyo, met one of Tokyo’s leading gangster bosses (murdered six months later) and drank turtle blood at a sayonara banquet with respectful members of Japan’s new secret police," Hughes recalled.

Hughes marvelled at Fleming’s passion for accuracy in plotting the Bond adventures. As an ama girl emerged from the water at Mikimoto Island, Fleming placed a hand on her bare shoulder, since "You must touch to get the precise texture of wet feminine skin." Eating fugu in Fukuoka, he used the hot end of a match to confirm that his lips had temporarily numbed. In Matsuzaka, he authentically spat shochu over the beer-fattened cattle. In the Shimabara brothel in Kyoto, he worked out "how many ronin could have eaten in the great ground-floor kitchen … while their daimyo lords feasted, roistered and wrenched" upstairs. At the Nijo Jinya, the trio spent two hours exploring its fiendish secrets for spying on daimyo who dared conspire against the shogun in the nearby Nijo Castle.

When Hughes and Saito bade farewell to Fleming at Haneda, they would never see him again. He died in 1964 of a heart attack, aged 56.

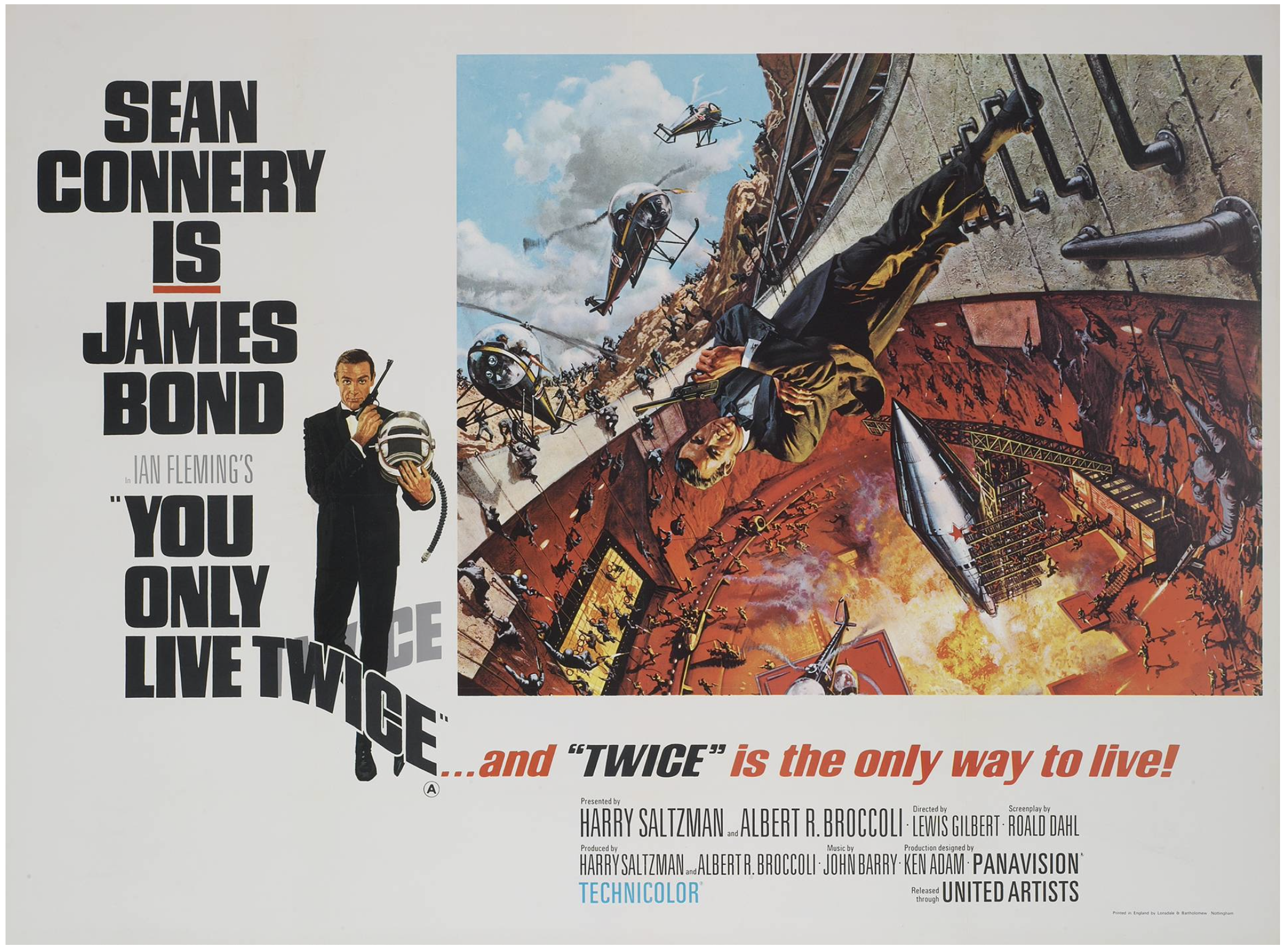

Caricatured in You Only Live Twice

In the book and subsequent film of You Only Live Twice, Hughes was the model for Dikko Henderson, head of the "Australian secret service" in Tokyo. Dikko is unflatteringly likened to "a middle-aged prize fighter who has retired and taken to the bottle. His thin suit bulged with muscle round the arms and shoulders and with far round the wrist. He had a craggy, sympathetic face, rather stony blue eyes, and a badly broken nose".

Saito became Tiger Tanaka, head of the "Japanese Secret Service," a former spy and kamikaze pilot. He emerges as a caricature of a well-bred nationalist who despises the Americanisation of Japan. Unsurprisingly, this fictional speech, worthy of Yukio Mishima in full flight, was cut from the 1967 film:

"For the time being," he said with distaste, "we are being subjected to what I can best describe as the 'Scuola di Coca Cola.' Baseball, amusement arcades, hot dogs, hideously large bosoms, neon lighting--these are part of our payment for defeat in battle. They are the tepid tea of the way of life we know under the name of demokorasu. They are a frenzied denial of the official scapegoats for our defeat--a denial of the spirit of the samurai as expressed in the kami-kaze, a denial of our ancestors, a denial of our gods. They are a despicable way of life … Our American residents are of a sympathetic type--on a low level, of course. They enjoy the subservience, which I may say is only superficial, of our women. They enjoy the remaining strict patterns of our life--the symmetry, compared with the chaos that reigns in America. They enjoy our simplicity, with its underlying hint of deep meaning, as expressed for instance in the tea ceremony, flower arrangements, No plays--none of which, of course, they understand. They also enjoy, because they have no ancestors and probably no family life worth speaking of, our veneration of the old and our worship of the past. For in their impermanent world, they recognize these as permanent things just as, in their ignorant and childish way, they admire the fictions of the Wild West and other American myths that have become known to them, not through their education, of which they have none, but through television."

The Honourable Schoolboy

In 1971, Hughes started writing for the Far Eastern Economic Review, a respected Hong Kong magazine and "window on Asia" under its energetic editor Derek Davies, a former Hanoi station chief for MI6 in the late 1950s.

By the 1970s, Hughes had become a living legend for the breadth and depth of his knowledge of Asia. He makes a literary reappearance as ‘Old Craw’ in John Le Carré’s 1977 spy novel, The Honourable Schoolboy, part two of the superb "Karla Trilogy", said to have been inspired by Philby and Markus Wolf, the "man without a face" who headed East Germany’s foreign intelligence service.

Old Craw is an Australian journalist who works for MI6, and is doyen of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Hong Kong. "Old Craw was their Ancient Mariner. Craw had shaken more sand out of his shorts, they told each other, than most of them would ever walk over."

Le Carré pays homage to "the great Dick Hughes" in the acknowledgments. "Some people, once met, simply elbow their way into a novel and sit there till the writer finds them a place. Dick is one. I am sorry I could not obey his urgent exhortation to libel him to the hilt. My cruellest efforts could not prevail against the affectionate nature of the original."

Hughes died of liver disease in 1984 at the age of 77. I had last seen him a few years before, standing to attention against a wall in Hong Kong with his great bulk supported by a stick. It struck me that when the British governor of Hong Kong, Sir Murray MacLehose, greeted him, Hughes bowed his head, quite deeply.

Peter McGill is a U.K.-based writer. A former Tokyo correspondent of the Observer, he was the youngest-ever president of the FCCJ.