Issue:

October 2025 | Cover story

Ukrainian media: journalists in Japan and around the world have a stake in opposing Putin's war on democracy

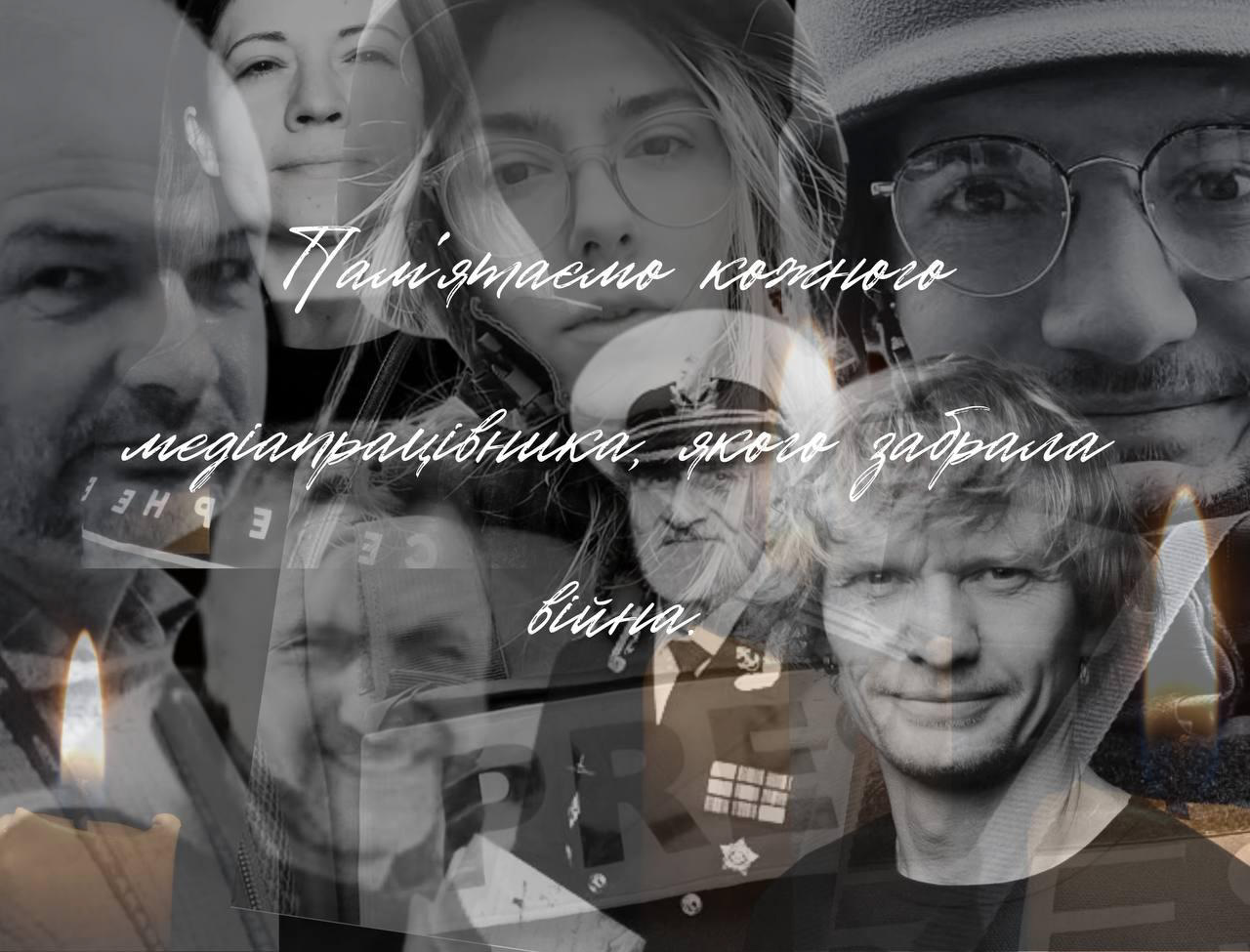

Amid the horrors in Gaza – the deadliest conflict for journalism in modern history – it is easy to overlook another lethally dangerous war for media workers. Since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, dozens of journalists have been tortured, snatched, killed or disappeared, according to media watchdog Reporters Without Borders. About 30 reporters are being held by Russia, their whereabouts and condition unknown, says the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine (NUJU). Some may already be dead.

The list of confirmed fatalities includes Ryan Evans, who died in August 2024 on assignment as a security advisor for Reuters. A Russian missile strike on a hotel in Kramatorsk killed him and injured two other journalists in what Ukraine said was one of many targeted attacks. The body of another reporter, Viktoriia (sometimes rendered as Victoria) Roshchyna, taken by Russian soldiers in 2023 was released earlier this year, showing “numerous signs of torture”, said investigators, including burn marks from electric shocks. She was 27.

Roshchyna had been reporting in Russian-occupied eastern Ukraine, investigating the disappeared: local politicians, church leaders, journalists and anyone else who had resisted Russian forces. A joint probe by the Washington Post, the Guardian, Ukrainska Pravda and others says these people are today being held in dozens of facilities dotted around the occupied territories and inside Russia. “Roshchyna fell victim to the very crimes she had set out to expose”, the Guardian concluded.

Nevertheless, frontline reporting in Ukraine goes on, insisted Sergiy Tomilenko, the president of the NUJU, which represents about 18,000 journalists in the country. Tomilenko led a delegation of his colleagues to Japan in September with a single message: don’t forget the Ukraine war or the people risking their lives to report it. “Independent media or journalists are a threat for Putin’s invasion,” which is why so many have fallen victim, he pointed out.

Russia “ignores international conventions and rules”, illegally detains journalists and civilians, and has barred the Red Cross and other international monitors from visiting them, Tomilenko said. He cited the case of retired journalist Irina Levchenko, who was abducted with her husband from occupied Melitopol in May 2023. His union only recently received a letter from her, confirming she is alive and being held in a prison in Donetsk. Russia has not yet admitted her detention, let alone cited any criminal charges.

Removing professional witnesses to the war, even retired ones, has been a key part of Russia’s strategy since the start, Tomilenko said. “The first stage, after occupation, was hunting for journalists. The second was to demand from Ukrainian journalists to be local propagandists.” Most refused, so Moscow dispatched what he calls “protagonists” from St Petersburg to the newly occupied territories in eastern Ukraine.

One result, he said, was a fake newspaper, produced in Rostov, Russia but distributed in Mariupol, involving only Russian protagonists and journalists, and printing mostly disinformation and lies. “Not a single Mariupol journalist worked in the newsroom.”

Among the claims that have circulated since is that Russia is “liberating” Ukrainians from a tyrannical Nazi regime, and that the transfer of thousands of children from the region has been done for “humanitarian” reasons. A survey by the Yale School of Public Health counters that Russia is in fact operating “a potentially unprecedented system of large-scale re-education, military training, and dormitory facilities capable of holding tens of thousands of children from Ukraine for long periods of time.”

Critics inside Russia have been silenced, too. Anyone questioning the war, or its horrific toll of more than a million dead or injured, is considered an enemy of the state, said Pavel Kangyin, contributing editor at Novaya Gazeta, an independent Russian newspaper recognised at the 2022 FCCJ press freedom awards. Using the expression itself – “no war” – in public is a crime, punishable with up to three years in prison, “and 15 years if you are a professional journalist”, Kangyin added.

Most of Russia’s independent media has been banned, blocked or declared “foreign agents” or “undesirable organisations”, RSF noted in its latest report. “All others are subject to military censorship.” Hundreds of journalists have fled or gone underground. This helps explain why there was so little opposition from ordinary Russians to the shelling of peaceful cities and the murder of Ukrainian civilians, according to Tomilenko. “Putin controlled everything … and mostly Russians support this war against Ukraine.”

Because much of the infrastructure in or near frontline territories has been destroyed, many people there have no internet access. Radio and television stations have been shut down so old-fashioned print media is their only source of independent news. Free newspapers have become vital in the frontline regions, Tomilenko said – “a symbol of resilience and hope”.

The frontline journalists include Vasyl Myroshnyk, who writes, edits and distributes Zorya (“Dawn”) in the Kharkiv region. Every week, Vasyl drives up to 400 kilometers to deliver his newspaper to villages that in some cases are just 100 meters from Russian army positions. Russian forces have shelled the newspaper’s office so many times since 2022 that its editor no longer says where it is, “for safety reasons”.

Media suppression means few independent voices reporting on Europe’s largest nuclear plant in Zaporizhzhia, in southeastern Ukraine, which has been under Russian control since the invasion. Russian troops have turned the plant into a military base and mined the territory around it, said Olga Vakalo, who edits and independent online media outlet based in Zaporizhzhia. Military equipment, weapons and explosives are located directly inside the turbine halls of power units 1, 2 and 4. The International Atomic Energy Agency has repeatedly warned of “serious safety risks” at the plant.

The fear, Vakalo said, is that Zaporizhzhia could become another Chernobyl, the world’s worst nuclear accident. Chernobyl, which is north of the capital city, Kyiv, went into meltdown after an explosion in 1986, showering much of Europe in radioactive debris. A concrete and steel sarcophagus seals reactor four’s lethal radioactive cargo, including uranium and plutonium. In February this year, a Russian drone pierced the roof of the sarcophagus. Russia of course denied intentionally targeting the plant.

Post-occupation, there are only 3,000 workers at the Zaporizhzhia facility, Vakalo said, far below the 11,000 on site before the Russian army arrived. “It's not enough for all safety measures at this power plant,” she warned.

The media should pay attention to how bad the situation in Ukraine could get, Tomilenko said. “We understand that world is tired,” he said, adding that he and his colleagues were exhausted too. “But we call all journalists and media not to stop covering the situation in Ukraine.”

He added: “We call on our colleagues in Japan to call to cover more, to prepare more reports, because if citizens in Japan, if citizens in Canada and other countries, will be more informed about the situation, they will be more supportive, and they will be against Putin or against tyranny, because the goal of Putin is not only to control Ukraine,” but to change the “world order and the democratic world”.

David McNeill is professor of communications and English at University of the Sacred Heart in Tokyo, and co-chair of the FCCJ’s Professional Activities Committee. He was previously a correspondent for the Independent, the Economist and the Chronicle of Higher Education

Dennis Normile is a contributing correspondent for Science and former president of the FCCJ.