Issue:

March 2022

Japan’s two oldest weekly magazines turn 100

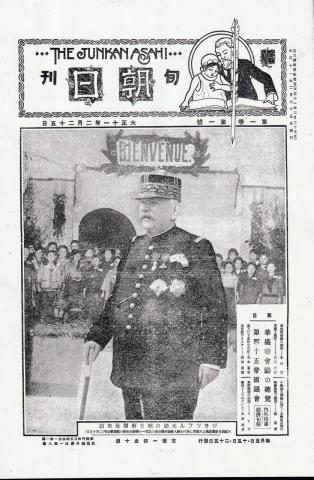

Right cover: Collector's item - The centennial edition of Shukan Asahi, which went on sale on February 15.

published on February 25, 1922

On February 25, 1922, The Asahi Shimbun launched Junkan Asahi, a magazine aimed at a general readership, to be published on the 5th, 15th and 25th of each month.

On the cover of its inaugural edition, beneath a wreath-festooned sign reading "Bienvenue" (welcome), was the beribboned Joseph Joffre (1852-1931), commander-in-chief of French forces on the Western Front during the first two years World War I. Joffre had visited the Kanto and Kansai areas the previous month, reciprocating the tour to Europe made the previous year by Crown Prince Hirohito, and had paid a courtesy call at the Asahi's head office.

The issue, which sold for 10 sen (a sen was 1/100th of a yen), consisted of 36 pages, leading off with a full page devoted to the Washington Naval Conference. The first half of the magazine focused mainly on domestic politics and international issues, with separate sections devoted to “Obei”(Europe and the U.S.) and “Shina” (China).

Junkan Asahi, however, was to last only four issues. From Sunday, April 2, it re-emerged as a weekly – Shukan Asahi – which has continued to this day.

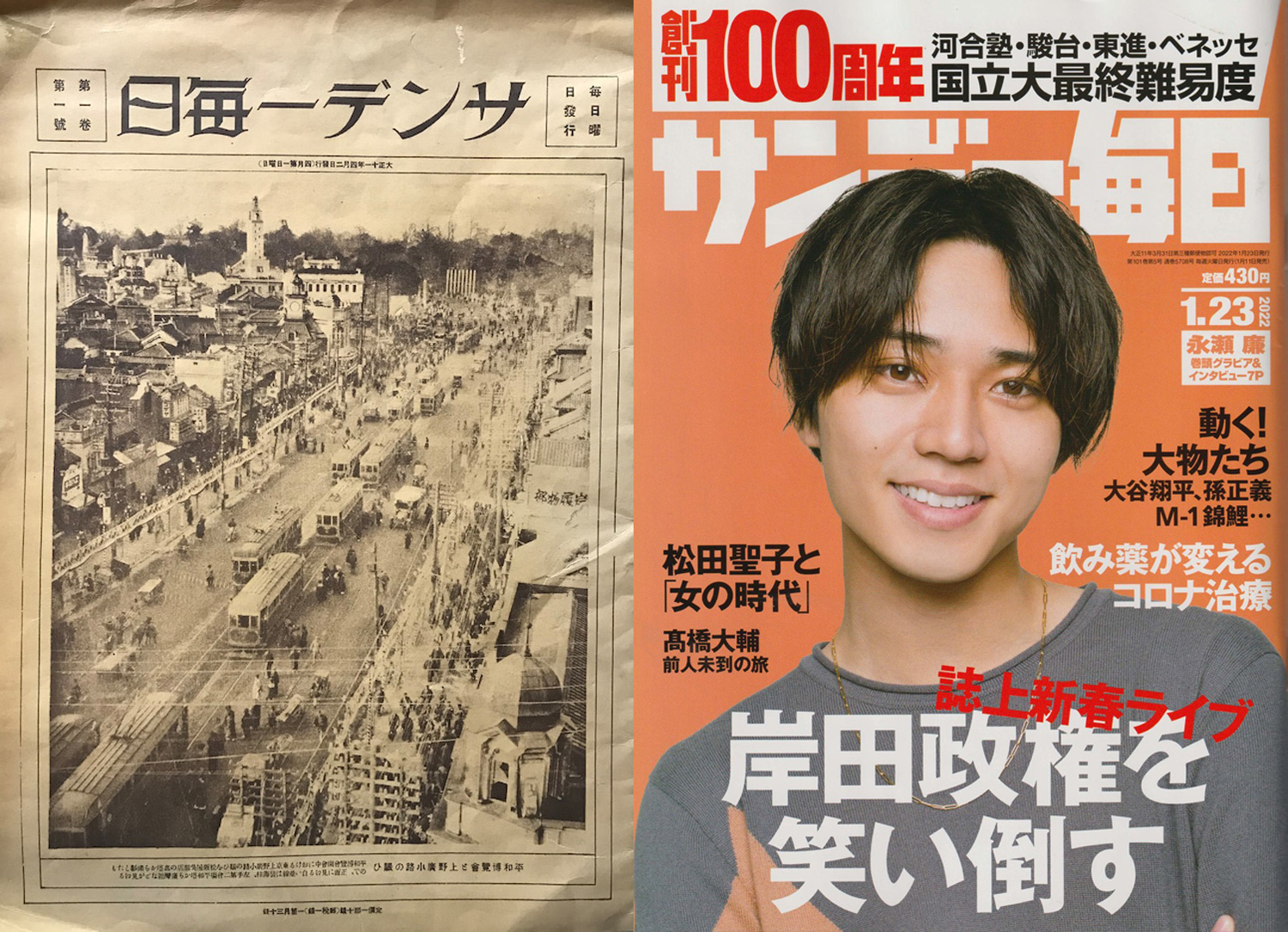

On the same day – in an unlikely coincidence – the rival Mainichi Shimbun launched its own weekly magazine, the Sunday Mainichi. While the Asahi can make legitimate claim to have come first, Japan's two oldest weekly magazines can be regarded as fraternal twins. The covers of their inaugural issues even carried photos from the same event: the Tokyo Peace Exposition in Ueno, which opened on March 10 and ran until July 22.

Right: The Sunday Mainichi has been celebrating its centennial with a banner across the top of its covers.

A century later, about 15 weekly magazines are in circulation, of which only four – the two abovenamed magazines, AERA and Spa! – have ties to their parent news organizations. A few of those that didn't survive will be eulogized later in this article.

In a short message to readers in its anniversary issue – dated 100 years to the day of the Junkan Asahi's debut – Shukan Asahi editor Kaoru Watanabe wrote: “How was our 100th anniversary commemorative issue? With thanks to the readers' support, this marks our 5,761st issue. The major incidents reported on our pages, as per the article (from page 96) reflect a century of Japan: disasters, war, recovery, prosperity, maturity and onward toward the future. None of these topics are lacking in emotional sentiment. But still, it's only been a century. Weekly Asahi will continue its run while ticking out the 'now.' I hope you'll continue to read our magazine for many years to come.”

The Sunday Mainichi is feting its centenary in a different way. From the start of the year, it has been serializing articles under the title “Sandee Mainichi ga mita hyaku nen no sukyandaru” (A hundred years of scandals as seen by the Sunday Mainichi). Some highlights included:

The publication of author Ryunosuke Akutagawa's will, following his suicide in 1927, at age 35. In it, he wrote that he felt a "vague insecurity" about the future.

The abrupt resignation of Prime Minister Sosuke Uno in 1989, after just 68 days in office, following a geisha's revelations of his parsimonious and callous mistreatment of her several years earlier.

The arrest of the notorious Sada Abe, who severed her dead lover's genitals following a romantic misadventure.

The bloody February 26, 1936, coup attempt in central Tokyo by disaffected army units.

Aboard the weekly bandwagon

The first weekly magazines, which targeted a largely male readership, were produced by Japan's national newspapers. That was to change when Shinchosha launched Shukan Shincho in February 1956. It was followed by Shukan Taishu (April 1958) and Shukan Jitsuwa (September 1958). Bungeishunjusha launched Shukan Bunshun in April 1959. Weekly Playboy was first published by Shueisha in October 1966, much to the displeasure of Hugh Hefner's U.S. magazine. (By using the name “Pureiboi” in katakana, it was able to hold off trademark challenges.)

In May 1988, The Asahi Shimbun established AERA (Asahi shimbun Extra Research and Analysis), a second weekly. Adopting a glossy A4 format, it was initially positioned as a challenge to the Japanese edition of Newsweek, which since January 1986 has been published by TBS Britannica).

Another A4 weekly with ties to a newspaper group, Fusosha's Spa!, was a spin-off of Shukan Sankei, which had been in print since 1952, and appeared in June 1988.

Then came the paparazzi-style shashin shukanshi (photo weekly magazines). Following the launch of Focus magazine by Shinchosha in 1981, four others – Friday (Kodansha, 1984-), Flash (Kobunsha, 1986-), Emma (originally a bimonthly from Bungeishunjusha, 1985-1987) and Touch (Shogakukan, 1985-1989) – jumped on the bandwagon, and the genre became known collectively as 3FET. Only Friday and Flash are still being published.

By the wayside

* Shukan Tokyo

Originally produced as an insert in the Saturday edition of The Tokyo Shimbun from August 1950, it boasted a circulation of 600,000. It shifted to separate sales, which saw circulation fall to around 350,000 copies, and folded in 1955.

* Shukan Yomiuri/Yomiuri Weekly

Produced as a weekly from 1952, it changed to its English name, with a glossy A4 format, in 2000. Its final issue appeared in December 2008.

* Shukan Hoseki/Dias (Kobunsha)

Launched in October 1981, it reveled in lowbrow vulgarity, with photographers accosting young women on street corners and inviting them to bare their breasts. After changing its name to Dias (in A4 glossy format) from July 2001, it folded one year later.

* Weekly Heibon Punch (Magazine House)

Launched in April 1964, it became the favorite of Japan's baby boomers, with circulation reaching 1 million copies a month. It lasted until 1988.

When weeklies made headlines

The scoops, scandals and sleaze involving the weeklies could be the topic of an entire future article, so to whet readers' appetite, I'll limit the count to just three.

Kazuyoshi Miura: Beginning in January 18, 1984, Shukan Bunshun launched a series of investigative articles titled “Giwaku no Judan” or “Bullets of Suspicion,” which alleged that on November 17, 1981, while on a visit to Los Angeles, Tokyo businessman Kazuyoshi Miura had arranged for the fatal shooting of his heavily insured wife, Kazumi, in what was made to look like a robbery attempt.

Miura, described in Newsweek as “the man they love to hate”, was only found guilty of attempted murder in a separate incident. He kept himself occupied in prison by suing the media, to the extent that he became the most prolific, and successful, libel litigant in Japan's history, winning about 70% of his cases.

Miura committed suicide on October 10, 2008, in a Los Angeles jail cell, following his extradition from the U.S. territory of Saipan. He was 61.

Aum Shinrikyo. From 1989, Sunday Mainichi developed an adversarial relationship with the doomsday cult Aum Supreme Truth. Investigative reporter Shoko Egawa, who tracked the cult’s activities from its onset, noted that within 18 months of its incorporation, Aum had been involved in no fewer than 60 civil and criminal lawsuits, with many targeting the weeklies and sports tabloids. Angry groups of cultists also began to invade newspaper and magazine offices, forcing them to increase security.

An article in Shukan Shincho may have set the stage for the March 20, 1995, sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway system. That magazine's issue of January 19, 1995, ran an article titled "The judges in a lawsuit against the Aum Shinrikyo were sarin victims."

The release of sarin nerve gas the previous June 27 in Matsumoto, Nagano Prefecture, killed seven people and sickened several hundred others. Shincho was the first publication to offer a logical explanation for the Matsumoto mystery, which had baffled the police.

The magazine reported that after Aum allegedly used a dummy company to purchase a tract of land in the city in June 1991, its former owner petitioned the Matsumoto branch of the Nagano District Court to invalidate the sale. The court's ruling on the dispute was expected in late June or early July. Three judges hearing the case lived in a dormitory hit by toxic gas fumes, and had to postpone their ruling on the land suit after falling ill from exposure to the gas.

Hair nude: Another turning point involved the decision by some weeklies to run so-called "hair nude" photos – undraped frontal views showing female pubic hair, which had previously been illegal. Upon publication several years earlier of art books with nude photos, police had begun to relax the ban, and some weeklies soon jumped on the bandwagon.

In June 1996, an article in The Asahi Shimbun listed the names of Japanese-language publications that foreign carriers flying into Japan were selectively screening out as offensive.

By October 1996, Japan Airlines, All Nippon Airways and Japan Air System had announced they would halt the free distribution of Shukan Gendai and Shukan Post on their flights.

"On a plane in flight, the offended person has no means of walking away," commented journalism critic Masaki Kataoka, explaining the carriers' rationale. "It's true that what constitutes obscenity changes with the times, but I think the magazines have already gone too far."

An article in Shukan Jitsuwa pointed out that the cuts by the airlines amounted to 4,000 copies a week – less than 1% of the respective magazines’ newsstand sales.

"We don't put together content according to whether or not it is going to be carried aboard an airline," Shukan Post's editor, Norimichi Okanari, was quoted as saying. "We weren't even aware that the airlines were buying them. I doubt if their move will have any impact on our sales."

Post-bubble decline

A magazine’s shelf life is generally three to five days at kiosks and convenience stores, and one week at major bookstores. As bookstores in Japan continue to close, convenience stores have assumed a larger share of overall magazine sales.

With successive boosts in the consumption tax, moreover, magazine prices have increased, and currently range from ¥ 420 to ¥550. As wives reduce their husbands' monthly allowance, the higher prices may also contribute to declining sales.

Below are weeklies' Audit Bureau of Circulation figures, in descending order of sales, comparing the first two quarters of 2011 with the first two quarters of 2021.

- Shukan Bunshun 477,391 → 257,667

- Shukan Gendai 384,592 → 193,914

- Shukan Shincho 384,373 → 145,687

- Shukan Post 302,617 → 136,400

- Weekly Playboy 157,731 → 74,280

- Shukan Taishu 168,498 → 73,398

- Shukan Asahi 151,061 → 50,797

- Shukan Asahi Geino 97,583 → 49,700

- AERA 95,177 → 32,168

- Sunday Mainichi 76,785 → 27,738

Comparative figures were not available for three other weeklies. Their names and estimated recent sales figures are as follows: Shukan Kinyobi (13,000 as of September 2018); Newsweek Japan (60,000, undated); and Spa! (88,810 in the first quarter of 2021).

Most weeklies have been slow to harness the internet, with Shukan Bunshun an exception. In an interview in Tsukuru magazine in October 2021, Shukan Bunshun's then-editor, Manabu Shintani, discussed his magazine's efforts to expand revenue sources beyond the print edition, charging online subscribers ¥300 yen per article. One of its scoops, a scandal involving a Japanese entertainer, was said to have driven more than 40,000 sales, generating ¥12 million from that article alone.

Another outlet for Shukan Bunshun has been sales to the gossipy "wide shows" on TV networks, for which it charges a flat fee of ¥50,000 per article and ¥100,000 for material that includes video footage.

As the weekly magazines begin their second century, clinging to their existing business models may not be enough to ensure their survival.

An invaluable resource

An article about magazines would not be complete without an introduction to an invaluable resource for writers of all stripes: The Oya Soichi Bunko in Setagaya Ward.

Named after Oya Soichi (1900-1970), a well-known journalist who bequeathed his enormous collection of magazines, the library holds over 800,000 Japanese magazines of 12,000 types dating from the 19th century to present times. A ¥500 admission fee covers initial database search services of up to five topics. Copies from back issues cost ¥85 per page, with an additional charge for color copies.

The Oya Bunko, which in May will mark its 60th anniversary, is open six days a week. It is located about 10 minutes on foot from Hachimanyama Station on the Keio Line.

Mark Schreiber's first encounters with weekly magazines came in the 1970s while reading over people's shoulders on trains during his commutes to work. He finally began buying them, and has been addicted ever since.