Issue:

September 2022 | Letter from Hokkaido

Olympic scandal could derail Sapporo’s bid for the 2030 Winter Games

A major city in Japan with an Olympic dream decides to bid for the winter event. The mayor and local businesses rush to assure voters that existing facilities can be used, costs will be minimal, and the post-Games economic benefits will be huge. But an Olympic scandal suddenly emerges, creating PR concerns among bid supporters. Public opposition rises, as voters begin to suspect that the bid is little more than a waste of taxpayers' money for the benefit of greedy Olympic officials.

To me, recent events related to Sapporo’s quest to host the 2030 Winter Olympics and Paralympics have the feel of déjà vu all over again. I suspect the Number 1 Shimbun editor Justin McCurry feels the same. That’s because two decades ago, both of us were in Osaka for our respective publications covering Osaka’s failed bid to host the 2008 Summer Olympics.

Then, as is now as the case in Sapporo, the Osaka mayor and Kansai business community rushed to assure everyone the Games would be a ticket to local economic revitalization. The Osaka bid proceeded amid allegations that candidate cities of were attempting to bribe International Olympic Committee (IOC) officials. The Sapporo Olympic bid is taking place as a powerful former Dentsu executive and Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics official is being investigated on suspicion of bribery. And, like Sapporo’s small, nascent opposition at present, the Osaka bid was openly protested by an admittedly small group – led by the Kansai-based editor of a fishing publication, Tsuri Sunday – that nevertheless reflected the unspoken concerns among many Osaka residents.

But there are some key differences between the Osaka and Sapporo bids. In the final IOC vote in the summer of 2001, Osaka was eliminated in the first round, with the Games awarded to Beijing. Sapporo heads into the 2030 Winter Olympics contest with important technical advantages over its main rivals, Vancouver and Salt Lake City. Starting with the quality of the powder snow. As any FCCJ skier knows, Niseko and Sapporo are said to have some of the best in the world, and bid supporters are heavily relying on that reputation.

Sapporo’s decision to go after the 2030 Games comes almost two decades after the city first considered bidding for the 2020 Summer Olympics in 2003. That idea was abandoned after it was estimated the total cost would be ¥1.8 trillion (The final cost of the Tokyo Olympics was about ¥1.4 trillion).

After Tokyo was awarded the 2020 Games in 2013, Sapporo decided to go after the 2026 Winter Olympics, with the host city to be named in 2019. But a 2018 earthquake in the Sapporo area created fears in city hall that spending money on a bid at that time would invite a political backlash. The plan changed, and Sapporo decided focus on the 2030 Games, which will be awarded next year, after the area had fully recovered from the quake.

Why did Sapporo decide to bid? Cities usually offer pompous platitudes and pretentious rhetoric about their reasons for wanting to host an Olympics. Refreshingly, the mayor and city hall were more direct.

“Sapporo is facing population decline, a low birthrate and an aging population, and it is necessary to realize a symbiotic society, renew the infrastructure, and take measures against climate change,” says the official English-language outline of plans for the Games. The solution to this pressing need for urban renewal? The 2030 Winter Olympics and Paralympics.

Winter Olympics - Wikipedia

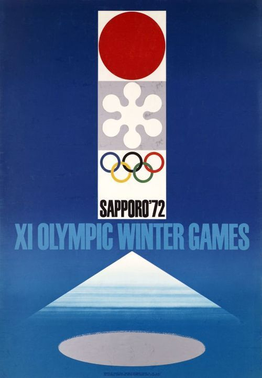

A Sapporo 2030 Olympics would take place between February 8-24 with 109 events in seven sports. The 2030 Paralympics would take place from March 8-17 with 80 events in six sports. The city says 92% of all events would take place in pre-existing facilities, some of which were used for the 1972 Sapporo Winter Olympics. Sapporo's mayor, Katsuhiro Akimoto, has promised the total budget will be between ¥200-220 billion.

How do residents feel? A survey the city conducted earlier this year showed a majority agreed with the bid. But local media polls painted a different story, showing either that residents were split almost 50-50 or that a slight majority were opposed. Akimoto insisted a “silent majority” of support was there, even as the city assembly voted in June against proving that by holding a referendum on the bid.

Just over two months later, on August 17, news broke that Tokyo prosecutors had arrested former Tokyo Olympic organizing committee member Haruyuki Takahashi on suspicion of receiving bribes from Aoki Holdings, a manufacturer of men’s formal wear.

Takahashi denies the charges against him, but the scandal has caused shockwaves in Sapporo. Akimoto and the Hokkaido governor, Naomichi Suzuki, are nervous that the scandal is turning public opinion against the bid. One Hokkaido media poll in late August showed that 72% of respondents opposed it. Akimoto will visit IOC president, Thomas Bach, in Switzerland later this month to try to reassure him that Sapporo still wants the Games. The former Japanese Olympic organizing committee president, Seiko Hashimoto, a Winter Olympics bronze medalist and upper house member from Hokkaido, is no doubt delivering the same message to her IOC contacts.

The IOC will decide in December which candidate cities make the final cut, and the level of public support will be a key factor in its decision. The 2030 winner will be announced in Mumbai next May, just over a month after Akimoto faces a re-election campaign. At the moment, he is heavily favored to win, but the ongoing scandal could change that.

Visible opposition to the Sapporo bid has yet to reach the level I saw in Osaka two decades ago. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t there, as the recent media poll showed. Before the scandal, Sapporo officials were quietly confident that their city was preferable to its rivals, based mainly on the quality of its snow and the area’s reputation as a major international winter sports destination. That confidence, like snow in late March, is melting rapidly, and as the Takahashi-Aoki scandal continues, nobody in Sapporo is quite sure how to stop it.

Eric Johnston is the Senior National Correspondent for The Japan Times. The views expressed within are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of The Japan Times.