Issue:

February 2024

Almost 30 years have passed since the monthly magazine was pulled amid an antisemitism row, but the media have found new targets

In 1997, the Tokyo District Court was tasked for the first time with ruling on a new question: During World War II, had Nazi Germany systematically murdered Jews by poison gas in concentration camps? Japanese Holocaust denier Aiji Kimura had sued both an academic and freelance journalist, as well as their publisher, for allegedly libeling him in the weekly magazine Shukan Kinyobi. In an earlier ruling, a judge remarked that the Holocaust as an event was so removed from Japan, that, in his opinion, the court could not “decide whether or not gas chambers existed,” but only whether Kimura's suit had merit as a libel case. In February 1999, however, the court issued the following as part of its ruling:

… as acknowledged by the International Nuremberg Trial, Nazi Germany murdered in its concentration camps great numbers of Jews by poison gas. This fact is also acknowledged as the general historical understanding in Japan. The destruction of the Jewish people is known as the Holocaust.

(Kajimura et al., 1999, quoted in Kowner, Tokyo Recognizes Auschwitz, 2001)

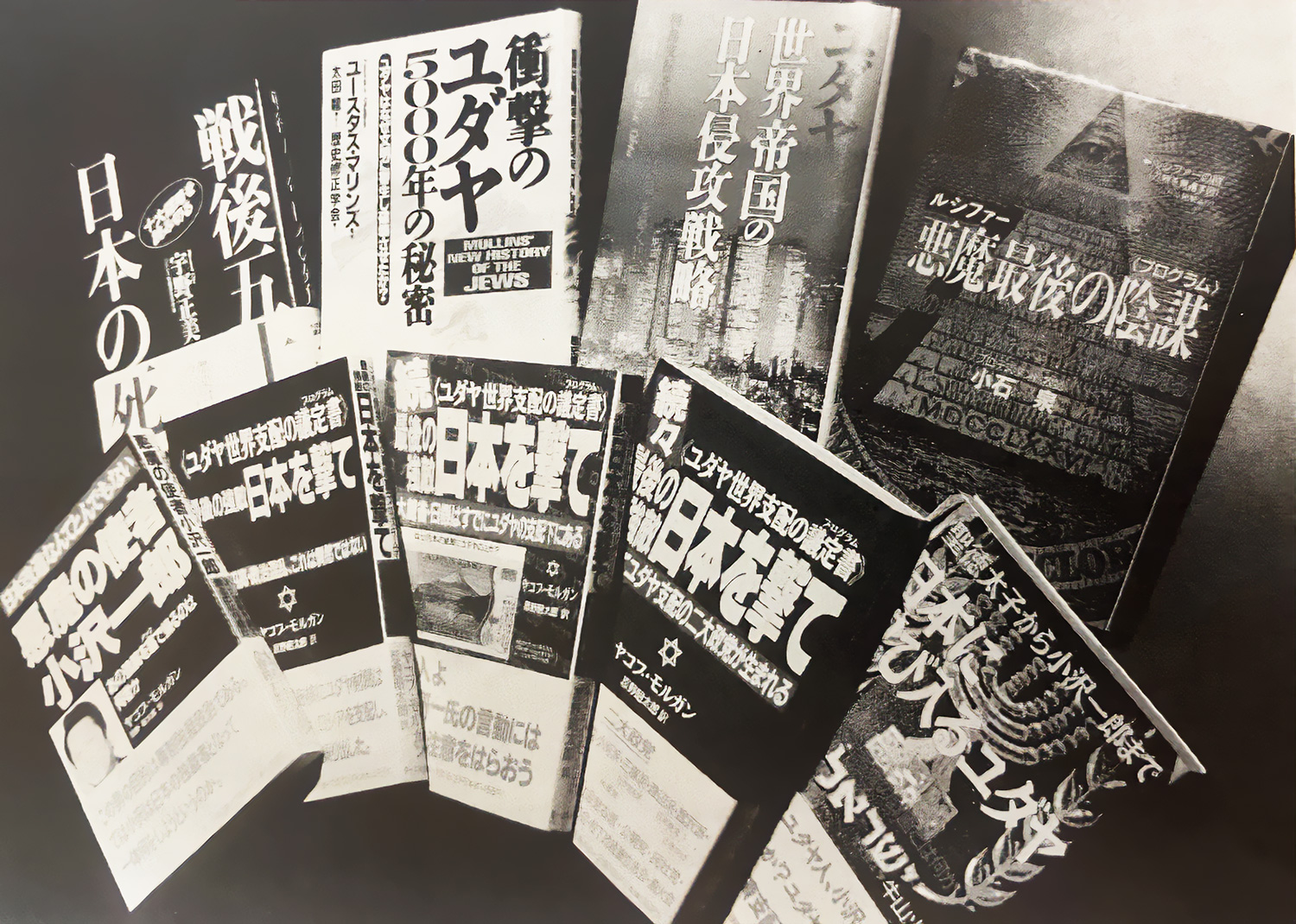

From the late 1980s, Jews in Japan had raised growing concerns over the widespread popularity of publications that became a ubiquitous feature in bookstores across the country during the years of the so-called bubble economy, offering up conspiracies and defamatory tropes about Jews as an explanation for Japan’s economic woes. Books and articles denying the Holocaust, while equally vexing, were a much newer phenomenon.

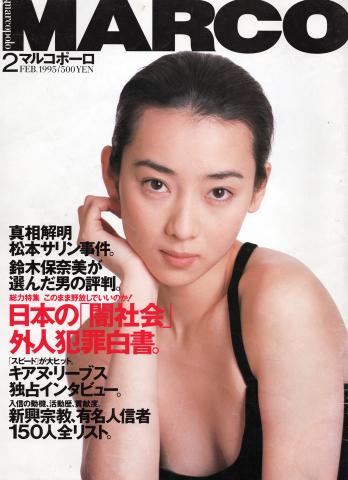

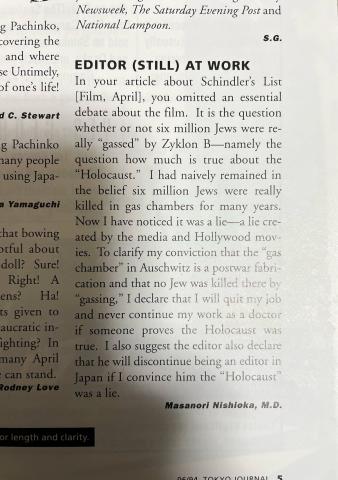

Several years before Kimura’s day in court, the issue of Holocaust denial stirred a major controversy in Japan. In January 1995, Marco Polo, a glossy A4 monthly magazine marketed by publisher Bungei Shunju to young professionals, published a 10-page article titled Post-War History’s Greatest Taboo: The Nazi ‘Gas Chambers’ Never Existed. The author, a physician named Masanori Nishioka, was already known for his revisionist views in Tokyo's English-language media.

From the time the magazine hit newsstands on January 17, it took less than two weeks for an international protest to materialize, and for Bunshun to take a step unprecedented in post-war Japanese publishing: close a major publication in response to protest.

The February 1995 issue of Marco Polo's appearance on January 17 initially attracted little attention, as before dawn the same morning a devastating earthquake struck Kobe and Awaji Island, dominating news coverage for the 10 days that followed.

However, on January 25, the evening editions of both the Asahi Shimbun and Nihon Keizai Shimbun, reported that an American “Jewish group” was calling on advertisers to boycott Marco Polo over an article they deemed offensive. Both newspapers noted that Germany's Volkswagen AG had already declared they would suspend their ads in Bunshun’s publications “until the situation was clarified”.

Deflecting a protest by Israeli diplomats, the assistant editor at Marco Polo had initially refused to run an apology and retraction of Nishioka's article.

But on January 30, Bunshun abruptly announced that Marco Polo would be shuttered and its staff reassigned, while its editor would lose his position. On February 2, Bunshun’s president, Kengo Tanaka, held a press conference in a packed ballroom at Hotel Okura to publicly apologize to Associate Dean of the Los Angeles-based Simon Wiesenthal Center (hereafter SWC), Rabbi Abraham Cooper, and, by extension, to the Jewish people.

In the flurry of coverage following Bunshun’s January 30 announcement, the Japanese papers and weeklies explained that an American Jewish group (the SWC) had contacted Marco Polo’s advertisers, organizing a boycott, after being alerted to Nishioka's article. But, as Rabbi Cooper of the SWC clarified during the February 2 press conference, the SWC and Jewish protestors in Japan never demanded that Bunshun shutter Marco Polo. The media would come to blame “Jewish pressure” for this closure, and Bunshun only offered the admission that Nishioka’s piece “lacked fairness”, while never explaining what made it so problematic.

In examining the Marco Polo affair, there is no shortage of offhand mentions of this rising tide of print antisemitism in Japan. Even the iconoclastic investigative magazine Uwasa no Shinsō – while attacking the SWC’s protest as unfair – acknowledged the popularity and availability of books offering conspiracies and distorted images of Jews. Relatedly, when University of Illinois professor David Goodman was asked to contribute to special coverage of Marco Polo in Takarajima 30, he suggested they simply re-print an article he had written years prior, because, “It is not unusual for Japanese newspapers and magazines to publish articles [like Nishioka’s.”

Yet why had a Jewish protest suddenly succeeded if, according to an interview with a “Jewish-American man, a long-time resident of Japan” in AERA’s Feb. 27, 1995 issue:

“We have been protesting to newspapers and magazines that carried the book ads. And yet, articles like this one in Marco Polo magazine have appeared again.”

One reason Jews in Japan were infuriated by Nishioka's article was that Marco Polo’s editorial staff had seemingly suspended objectivity with a lead-in that not only maintained the notion there was “little evidence to support the story that they [Jews] were killed in gas chambers in a premeditated manner”, but praised Nishioka’s piece as an “astonishing new historical truth!” Even magazines that blamed the SWC for stifling free expression in Japan tended to concede that the lead-in had flouted objectivity, as attested to the Israeli Embassy’s refusal to consider a rebuttal as chronicled in the February 19, 1995 edition of Sunday Mainichi:

Yoshito Takigawa, a spokesperson for the Israeli Embassy who was part of the protest to Bunshun headquarters, said: “We were told to ‘write a rebuttal,’ but if we did so, the position of Marco would be unclear. We declined because we would be troubled if they didn’t take clear responsibility for publishing this junk, nonsense article.”

Shukan Bunshun already suffered somewhat from a weakened stature after having been rattled by two other recent protests. Following unfavorable coverage of Japan Railways and Empress Michiko, Bunshun had been hit by limited boycotts, hurting its bottom line.

These recent successes of other groups’ protests, as well as the disregarding of Jews' protest to Hanada in 1993 about Shukan Bunshun's running full-page ads for antisemitic publisher Daiichi Kikaku Shuppan, made an ad boycott seem feasible as the next step. As critics and journalists autopsied Marco Polo’s demise, speculation emerged as to whether its cancellation was the result of infighting between corporate factions, or perhaps a pretext to close a magazine that was hemorrhaging company resources in a contracting post-bubble economy.

One striking thread across so many of the articles written about Marco Polo is encapsulated in how many critics portrayed an ad boycott as inherently at odds with Japanese society, and harmful to the future of free speech. Some even went so far to suggest that by protesting in such a way, Jews would now become disliked in Japan. For instance, conspiracy-debunking author Hiroshi Yamamoto, writing in Takarajima 30, said:

… many Japanese are unaware that such a debate [on the Holocaust’s veracity] was taking place. To one-sidedly decide, “This is wrong,” will leave people who don’t know more thinking that this is “suppression of speech.”

Using even stronger language, investigative journalist Shoko Egawa wrote in Seiron in April 1995:

I fear that this action by the Wiesenthal Center is not just unfair, but may also contribute to a vague sense that Jewish people are to be feared.

...

This incident will make the issue of Jews a complete taboo … Criticism of Jews, not just Holocaust denial, will disappear from the media for the time being.

The media’s focus on the SWC as a foreign group and the non-coverage of local Jewish activists’ role in the Marco Polo affair obscured how rather than being sudden, foreign, and unprecedented, Jewish protest emerged from companies like Bunshun. Mirroring then-Bunshun president Tanaka informing the SWC’s Rabbi Cooper that “Japanese history and culture are so widely different and removed from those of the Jews,” the Holocaust and Jews were depicted as completely foreign to Japan, despite years of Jewish protests from inside Japan. This

"foreignness" to which the protest of Marco Polo was assigned appears more ideological than actual – but with real implications for how this group of local activists has been written out of history, and how the Marco Polo affair has come to be seen as an issue of free speech by Japanese versus pressure from foreigners.

Looking back at Marco Polo almost 30 years later, the post-mortem in the Japanese media feels hauntingly familiar. Specifically, the closure of monthly magazine Shincho 45 magazine in 2018 and Kadokawa’s recent announcement, then cancellation, of a Japanese translation of the anti-transgender book, Irreversible Damage, come to mind. In both these cases, protests have been driven by Japan’s LGBTQ+ community decrying how the mistruths about them on the printed page have serious consequences for their daily lives.

Yet coverage of these protests has consistently suggested that foreign forces are influencing what gets published in Japan, or that even the issues themselves are simply, in the words of former Bunshun president Tanaka, “so widely different and removed” from Japan. Moreover, when Shincho 45 and the Japanese translation of Irreversible Damage were cancelled, neither publisher offered any explanation of what content was at issue. In such a case, there is neither an acknowledgment of the problem nor a chance for education. That stance is perhaps even more injurious to open exchange of ideas in society.

As the Tokyo District Court ruled in the Kimura libel case, contemporary debate about the Holocaust wasn’t something that could be detached from history or the printed page. The court’s decision helps our understanding of both the causes and effects of media controversies in Japan, whether this applies to why Marco Polo was first protested by Jews in Japan or why the country’s LGBTQ+ people have protested irresponsible articles about them.

In both the Marco Polo and Shincho 45 cases, one crucial fact got lost in the ensuing rancor: that protests about prejudiced and untruthful speech often emerge from denying people a voice.

Dylan O’Brien is a PhD Candidate in Cultural Anthropology at the University of California, San Diego. His research examines how representations of Jews and Judaism in Japan interact with Jews living in Japan.