Issue:

November 2025

Fiberglass and plastic are as much a part of the Japanese garden as bonsai and gravel

A common response among non-Japanese when thinking of the Japanese garden, is to conjure up a random set of over-simplified signifiers, largely based on the traditional stone and stroll garden types, that largely fail to acknowledge the immense diversity of the form and its highly creative, sometimes contentious development. Little known to the non-Japanese, the conspicuously modern, sometimes transgressive landscapes that appeared in the post-war period could hardly have been more different from their antecedents in both form and materiality.

In the James Bond film, No Time to Die, the monstrous Blofeld, played by an improbable, but highly convincing Rami Malek, is pictured sauntering through a neo-Japanese garden built inside a biochemical plant on a disputed island somewhere between Japan and Russia. In this dystopian landscape, junipers, pruned into models of Japanese topiary, are made from Velcro, rocks from silicone.

It may be a contrived movie set, but in the contemporary Japanese garden, you will come across materials as synthetic as carbon fiber, translucent polycarbonate, and treated concrete. In an urge to be modern, to create small blasphemies in a form that has existed for over a millennium and a half, there are garden rocks made from shimmering fiberglass and hardened plastic.

A seminal figure in the creation of new, post-war gardens utilizing unorthodox designs and materials, was the polyglot, Shigemori Mirei (1896-1975). An iconoclast with a critical view of how Japanese gardens had stagnated, or turned into formalized exercises in acknowledging the past, Shigemori shocked the garden establishment by introducing materials like tinted tiles, concrete, and colored pebbles. Reacting to what he considered the stale formalism and duplication ad infinitum of garden forms, the art’s degeneration into mannerism and over-ornamentation, Shigemori believed that, in common with other art forms, gardens needed to evolve.

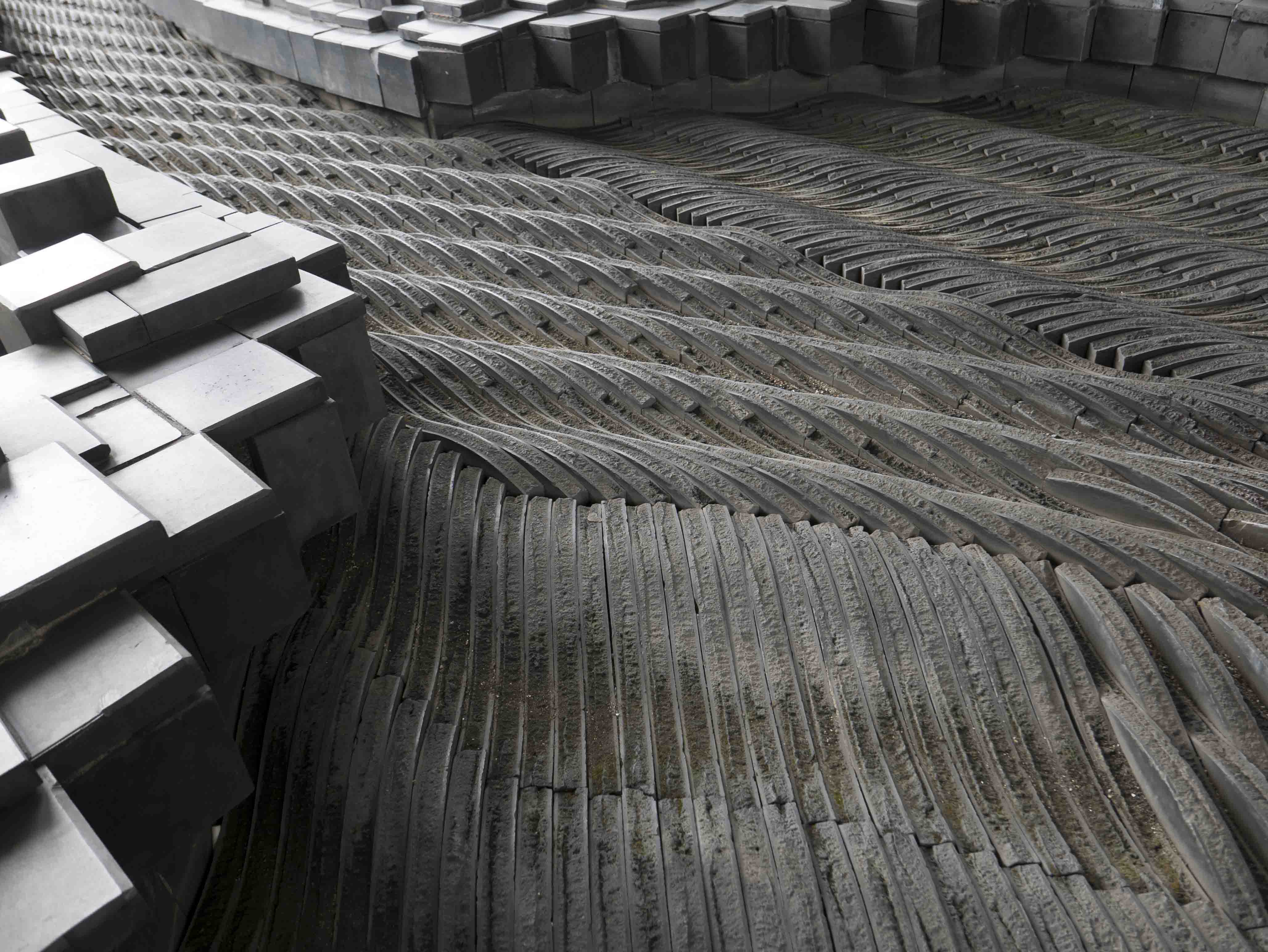

And they did. In Tange Kenzo’s 1958 design for the Kagawa Prefectural Office, we see for the first time the fusion of landscape designer and modern architect. Creating accessible space, a sharing, as opposed to coveting of space, the garden was a key moment in ushering in the movement from the private to public domain. In Tange’s conception, fluid forms were combined with geometrical lines, a spatial infrastructure more in common with the modern city than natural landscapes. Stark, dramatic contrasts were achieved by placing rocks, imposing primordial forms, against the reflective planes of glassed-in buildings. Sonorous natural sculptural forms complimenting the rationality of modern architecture, the duality of garden and buildings create a powerfully insistent monumentality. In an essay dating from the early 1960s called “The Secret of the Rock,” Tange would set forth his views on the preference for cut and incised rock over natural forms, writing that the results reflected “the will of the carver.”

In accord with garden designer Shigemori Mirei’s concept of the ‘eternal modern’, the work of Masuno Shunmyo straddles times zones with the assurance of a master. A good example of his strikingly original approach is the 1991 Canadian Embassy stone garden in Tokyo’s Aoyama-ichome district, regarded by many as a modern masterpiece.

The roughly cut edges and wedge holes of the stones have been left intact, revealing process and human intercession, while the larger rocks have been hollowed out to lessen their weight, a method unheard of in traditional gardens. Firmly affixed to the embassy structure, one wonders about the future of urban landscapes in Japanese cities, which are notorious for their scrap and build, rapid replacement approach to construction. Will gardens of the future be portable structures, readily dismantled, then reassembled in fresh locations like art installations or mobile homes?

Impermanence, the imminence of decay are concerns facing an abandoned garden on Odaiba Island in Tokyo Bay. Here, a grove of light emitting rods sprout from beds of carbon fiber: undulating surfaces of polished black granite, ceramic tiles and molded pads lap like waves against hard, white panels, rectangular units raised above the ground. A nest of taught cords cluster like a force field of high-tension wires. Architect Watanabe Sei Makoto’s 1996 Carbon Fiber Garden, an adjunct to his K-Museum design, basks incongruously, like a mass of unidentified space junk, at the center of the island.

A sign outside the fenced-in museum reads, ‘Temporarily Closed.’ Weeds are gaining tentative purchase on the edges of the garden, some of the soft tiles that resemble black bubble-pack, have fallen off, and the bristling silver rods, “environmental sculptures” in Watanabe’s words, are losing their original luster and virility. Time and a merciless exposure to the salt winds of the bay are conspiring to obliterate the garden. If the site is not restored and maintained soon, its barriers removed so that visitors can explore up close the tactile nature of its materials, erosion will gain the upper hand, turning the installation into a future ruin.

More commercially promising, with a steady trickle of visitors, the Enoura Observatory sits on its steep, terrestrial ledge, with views along the Izu Peninsula and out towards the ocean. A multi-disciplinary cultural project, the generous grounds include individual garden ensembles, a gallery, teahouse, pavilions, shrine, and an optical glass stage. The observatory opened in 2017. More additions are planned. Sugimoto has written prophetically of his “archaeoastronomical structures” being created in preparation for the probable collapse of civilization. “I am making a garden,” he asserts, “that will devolve beautifully into ruins of stone.” With the Enoura Observatory project, Sugimoto has created an assemblage, filled not with dust and rubble, the inert debris of time, but enduring stone mysteries for the future to puzzle over.

At its most radical, the modern meta-garden dispenses entirely with natural elements. The Shonandai Cultural Center, which includes a children’s museum, civic theater and planetarium, is an example of an entirely fabricated landscape, whose only natural component is water. Its creator, architect Hasegawa Itsuko, defines the composition’s mash of plaza pools, pyramidal roofs, spheres and an undulating stream, as “another nature.”

Located in Fujisawa, a Tokyo bedroom community, Hasegawa has talked about the “liquidity and diversity” of her sites, of the process of planning and conceiving architecture as a “work of making topography.” That fluidity and inclusion of landscape contouring is evident in the conflation of silvery surfaces, cage-like panels of steel, perforated aluminum trees, a riverbed made from tile, stained glass, vine-hung stainless-steel pergolas, and a set of cosmic spheres. The first woman to win an architectural competition of this type, reactions among the older male fraternity of Japanese designers were less than flattering, one well-known architect comparing her plan to a “naïve child’s drawing”, another deriding it as “gaudy, pop, idiosyncratic, and eccentric”.

The absence of natural materials does not appear to have diminished the popularity of the site, or its recognition by locals as a garden. This raises some interesting questions. If the unstated intention of the contemporary landscape artist is to create a modernist utopia, a futuristic garden prototype, is it possible to do so by means of purely synthetic materials?

The tiny island of Teshima, in the Seto Inland Sea, would seem an unlikely setting for a collaboration between international artist Tadanori Yokoo and architect Nagayama Yuko. Active since the 1960s, an engagement in science fiction, spiritualism, comic art, woodblock printing, and Japanese aesthetics surface in his creations, many of which seek, through dark, satirical humor and allegory, to usurp nostalgia.

The renovated and repurposed Yokoo Tadanori House Garden opened in 2013. First reactions are predictably mixed. Some visitors will be spellbound, others repelled at its apparent sullying of tradition. The occasional visitor will burst into hysterical laughter. No one will be indifferent, or without an opinion. An exercise in counter-intuitive aesthetics, a number of ornamental objects, a plastic crane and turtle, and blue and yellow mosaic tiles among them, items easily picked up in the discount corners of home centers, add to the curiosity, or effrontery felt by the viewer. In creating this disturbing, but iridescent work, Tadanori has deconstructed the Japanese garden and reassembled it in his own iconoclastic, color-saturated private vision of landscape art, following the artist’s early pop art style, described by writer Donald Richie as, “a hard-edged cartoon line in bright kindergarten colors”.

In common with contemporary art in general, the work poses more questions than answers. A rare instance of high kitsch in this genre, is he ridiculing the Japanese garden, or revering it? Are we gazing at a toxic interpretation or an anarchic masterpiece? One Japanese visitor, a middle-aged woman, confessed to me that she felt like vomiting. I heard a similar comment from a sickly-looking woman, dashing towards the exit for air at a Yayoi Kusama exhibition in Tokyo.

If the purpose of the modern garden is to unsettle us, to up-end and trick-wire expectations and assumptions, rotate our axis of perception, even make us a little nauseous, it succeeds brilliantly.

Stephen Mansfield’s new book, The Modern Japanese Garden, has just been published by Thames & Hudson.