Issue:

September 2024

Graves and monuments show Japan was not always a welcoming place for ‘haughty’ foreigners

Last December 3, I attended the burial of longtime FCCJ member Robert "Bob" Kirschenbaum at the Yokohama Foreigners' General Cemetery. While awaiting the arrival of the coffin, Bob's friends and colleagues assembled in the older part of the cemetery, whose gate at the foot of the hill is adjacent to the Motomachi shopping street. And there, I found myself standing before three graves. The inscription on the largest one, whose stone marker lies horizontal to the ground, reads:

Sacred to the memory of

C.L. Richardson

Late of Shanghai

Aged 28 years

Who was cruelly assassinated

by Japanese

on the Tocaido

Near Kanagawa

Sep. 14, 1862

Charles Lennox Richardson (1833-1862) was a Shanghai trader visiting Japan on his way back to the UK. Accompanied by three compatriots, he had set off on a horseback excursion to the Kawasaki Daishi temple. The four had picked an inauspicious time for sightseeing. The British legation in Yokohama had received an advisory from the Japanese authorities in Edo warning foreigners to stay off the roads that day, because feudal lords and their retainers were in the process of their sankin kotai rotation, an obligation imposed by the Tokugawa bakufu since 1635. And these samurai were “unaccustomed” to the sight of foreigners.

Relations between the diplomats and traders at Yokohama were said be prickly, so the warning was either not appropriately relayed, or perhaps it was disregarded. Whichever the case, it would cost Richardson his life.

About halfway to Kawasaki Daishi, at the village of Namamugi, the four encountered a large procession of samurai from the powerful Satsuma domain (present-day Kagoshima) traveling on foot in the other direction. The contingent included Shimazu Hisamitsu (1817-1887), regent of Satsuma.

Differing accounts of what transpired recall the proverbial tale of eight blind men describing an elephant. By some accounts, Richardson had harbored a haughty attitude toward Asians ("I know how to deal with these people"), cultivated by his encounters with the natives in Shanghai, but this was contradicted by later research that shows him to have been a well-mannered and sensible individual.

In any case, the four Brits, riding two abreast, hesitated in complying with the samurai demands – issued in a language none of them understood – to dismount and move to the roadside. Loud shouting and a brief melee ensued, and possibly one of the foreigners' horses may have panicked and bolted into the procession. A headman named Narahara Kizaemon dutifully unsheathed his sword and slashed at Richardson from behind, wounding him severely. (The authorities were later given a fake name, Okano Shinsuke, to conceal Narahara's identity.)

The wounded Richardson spurred his mount in the direction of Yokohama. He travelled around 700 meters before falling from his horse, pleading for water. There, another Satsuma samurai, Kaieda Nobuyoshi, caught up with him and administered the coup de grace.

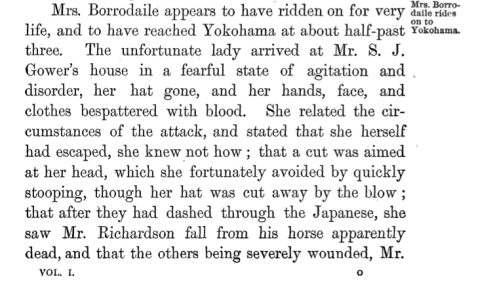

A post-mortem examination of Richardson's body showed ten mortal wounds. His two wounded compatriots, William Marshall and W.C. Clarke, managed to flee to the U.S. legation inside the nearby Hongaku-ji at Takashimadai (located between Higashi Kanagawa and Yokohama stations), where they were treated by Dr. James Curtis Hepburn (remembered as creator of the Hepburn romanization system). The woman, Margaret Borradaile, was badly shaken but uninjured, and made her own way back to the British legation in Yokohama to report her version of what had occurred.

The Satsuma rulers maintained the killing of Richardson was perfectly legal, as samurai in the feudal era claimed the right to strike down commoners who compromised their honor.

An outraged Great Britain was disinclined to accept that justification and on April 6, 1863, Yokohama-based Lt. Col. Neale issued an ultimatum demanding “the immediate trial and capital execution ... of the chief perpetrators of the murder of Mr. Richardson and of the murderous assault upon the lady and gentlemen who accompanied him," along with payment of £25,000. The government was given 20 days to reply, after which, if no satisfactory reply was forthcoming, "The ships destined to proceed to Kiushiu [sic] will then immediately leave."

After a frustrating series of delays, tensions between the two sides continued to mount. In August a squadron of Royal Navy ships embarked on an ill-prepared punitive expedition to Kagoshima – referred to as the Anglo-Satsuma War – bombarding the city's mercantile quarter and burning down some 500 homes, while suffering 13 deaths and 69 wounded to its own forces, leading Satsuma to claim victory. Later that year, Satsuma paid Britain £25,000 (equivalent to £3,000,000 in 2023), which it had borrowed from the Tokugawa treasury, never bothering to return it.

Marshall and Clark survived their wounds and were eventually buried next to Richardson. In addition to the three graves in the foreigners' cemetery, history buffs can visit the spot where the fatal clash took place, on the old Tokaido (marked on contemporary maps as Namamugi Kyudo), where a signboard was posted in January 2009 at 25-41 Namamugi 4-chome, Tsurumi-ku, Yokohama by the Namamugi Research Museum. The text, in archaic Sino-Japanese, contains a brief description of the incident.

Walking distance from Namamugi station on the Keikyu Line, close to the entrance to Yokohama's Kirin Brewery, another memorial beneath the expressway marks the location of the spot where Richardson expired. Some years ago, it was moved about 80 meters eastward from National Highway 15 to make room for road construction.

To mark the 160th anniversary of the incident, in 2022 the Tsurumi Ward office set up yet another marker adjacent to the Namamugi elementary school, making for a total of three in the vicinity.

In the years just prior to the Namamugi Incident, two other notable killings aggravated relations between the foreign powers and the Tokugawa government. Chapters V and VI of The History of Japan, Book II -- 1853 to 1864, by British diplomat Francis Ottiwell Adams (Henry S. King & Co., 1875), contain a detailed contemporary account.

Like his more famous compatriot, the legendary Nakahama Manjiro (aka John Mung), Wakayama native Kobayashi Denkichi had been aboard a ship gone adrift in the winter of 1850. Rescued by an American sailing ship, the Auckland, he and his crewmates were taken to San Francisco. By 1857, following a series of misadventures, he had learned English and acquired British nationality. In 1858 he accompanied Great Britain's first ambassador, Sir John Rutherford Alcock, to Japan as interpreter to the British legation.

On January 29, 1860, Kobayashi was standing in front of the gate of the British Embassy at Tozenji Temple in Takanawa when he was attacked by two samurai wearing deep straw hats to hide their faces, who approached him from behind, thrust a short sword into his back and fled. The dagger penetrated to the hilt. Denkichi staggered to the gatekeeper, who pulled the dagger from his back. He collapsed on the spot and was carried into the temple grounds on a wooden board and died shortly afterwards.

The British reported the murder of an interpreter at the embassy to their home country and asked the shogunate to arrest and punish the perpetrators. They were never apprehended, and their motive remains unknown. Some say that his death was the result of personal grudges, as Denkichi had a reputation for reckless conduct, being "short-tempered and arrogant". His former compatriots were said to have resented his "haughty attitude", dressing in Western clothes and reputedly arranging for Japanese women to be introduced to the British,

Kobayashi's funeral and burial took place at Korin-ji Temple in Azabu, attended by members of the British legation and two Gaikoku Bugyo (commissioners for foreign affairs, the forerunner of the foreign ministry) of the Tokugawa shogunate. His gravestone reads:

DAN-KUTCHI

JAPANESE LINGUIST

TO THE

BRITISH LEGATION

Murdered

BY

JAPANESE ASSASSINS

29th January 1860

A year after Kobayashi's murder, on January 14, 1861, the Japanese interpreter of U.S. Ambassador Townsend Harris, 28-year-old Dutch-born Henry Heusken, fell victim to a similar fate. Returning on horseback from a dinner with a Prussian official and disregarding the shogunate's warnings to foreigners to stay off the roads at night, he was attacked by a group of shishi (men of high purpose) from the Satsuma domain, at the Nakanohashi bridge. Eviscerated by sword cuts, he managed to flee to the nearby American Legation at the nearby Zempukuji but was pronounced dead shortly after midnight. Heusken left behind a Japanese wife and child.

A brass plaque formerly posted at Nakanohashi read:

Heusken Incident

Heusken, the interpreter at the first American legation in Japan, on the night of the fifth day of the 12th month of the first year of Manen (January 15, 1861), while returning from the Akabane foreign legation in Igura, was attacked on the Azabu side of the Nakanohashi bridge by people opposed to opening the country and sustained severe wounds. He was moved to his quarters at the American legation at Zenpukuji in Azabu. Twenty-eight years old at the time, his personality and potential will be greatly missed [but] he expired early the next morning. He was buried at the Korinji temple in Azabu.

Curiously, the plaque at Nakanohashi bore no information about the individual or organization that posted it. It may have been the work of an amateur history buff – which might explain why it was removed – although I would not discount it having been stolen by a collector. In any event, the last time I visited the bridge it had not been replaced.

Following Heusken's murder, rumors flew of impending attacks, which the authorities appeared to be unable to prevent. The Times of April 22, 1861 reported that "the foreign Ministers were informed by the Japanese Government that there were some 500 or 600 Zoonines [i.e., ronin] mediating a general massacre of the foreigners at Yokuhama [sic], the burning and pillaging of all their property, the murder of the consuls at Kanagawa, and the total annihilation of the various legations at Yeddo, with their inmates".

The mass attacks did not come to pass, but sporadic assaults on foreigners continued. It was not until March 1868 that the new imperial government issued an edict that sternly pronounced "... All persons ... guilty of murdering foreigners ... will be acting in opposition to Our express orders ... [and] shall be punished in proportion to the gravity of the crime ...."

Mark Schreiber is author of Shocking Crimes of Postwar Japan (Yenbooks, 1996) and The Dark Side: Infamous Japanese Crimes and Criminals (Kodansha International, 2001).