Issue:

September 2024

August marks the anniversary of the end of the Pacific War, but in Okinawa, the conflict continues

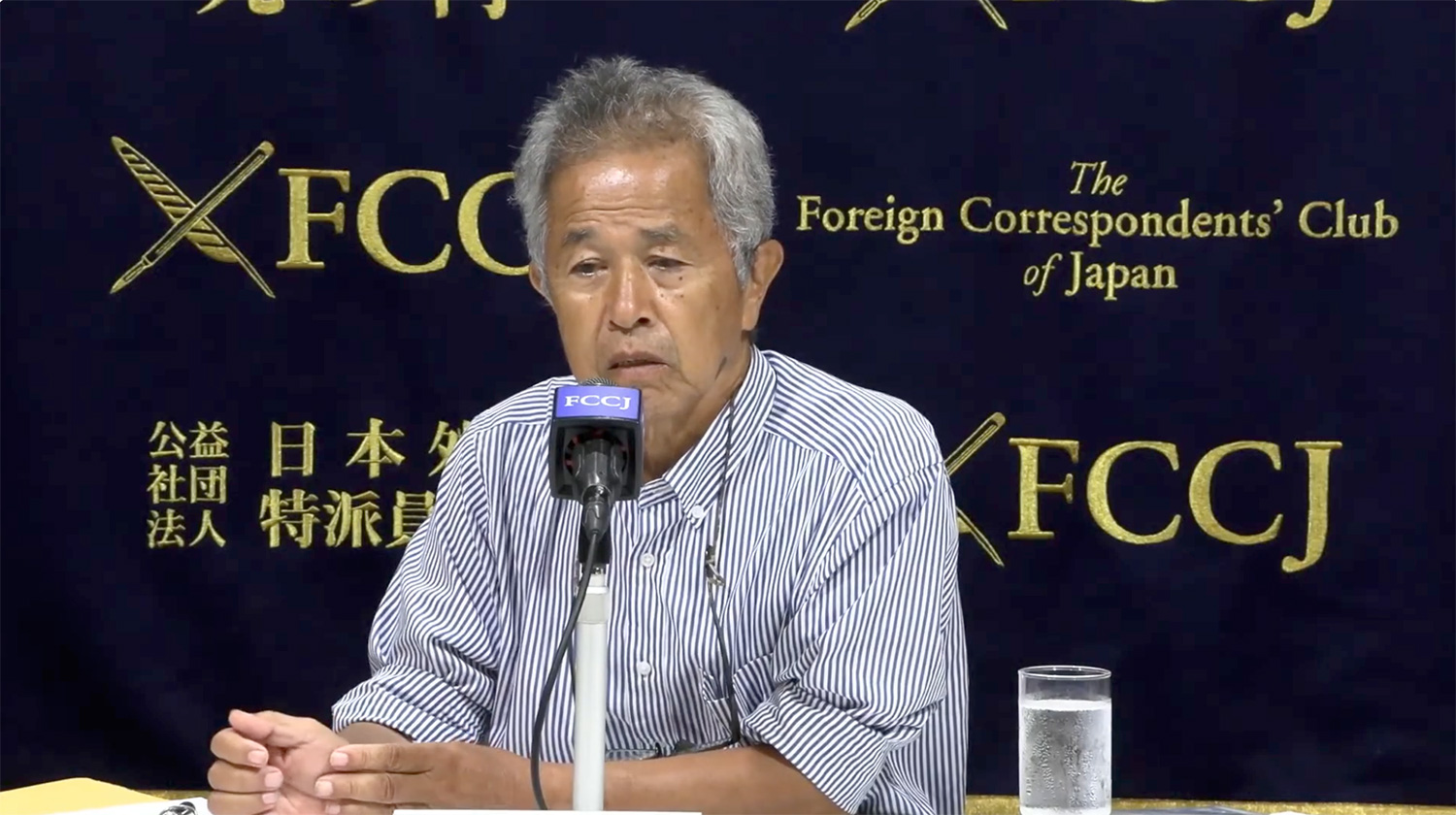

August is a month for remembrance in Japan, including O-bon - the annual festival for the dead - and commemorations for a war that ended nearly 80 years ago. Yet Okinawa remains embroiled in conflict - over territory, relations with the governments in Japan and the U.S., as it continues its quest for self-governance, according to prefecture’s governor, Denny Tamaki.

“Within Okinawa there is a difference of people’s perceptions on (the war’s end) depending on their circumstances,” Tamaki said in an appearance at the FCCJ in August.

“World War II came to an end, but looking at the situation that resulted in 70% of U.S. forces in Japan now being in Okinawa, and the U.S.’s involvement in various global conflicts and wars since, Okinawans are very sensitive to how bases have been utilized,” he added. “For these reasons, you can understand that for many Okinawans the war has not yet ended.”

Japan annexed the Ryukyu Kingdom in 1879 and in the modern era has often approached Okinawa with the same attitude it adopted during the Meiji Era. The U.S. returned Okinawa to Japanese control on May 15, 1972, two decades after the rest of the country.

Okinawa prefecture’s 161 islands make up only 0.6% of the country’s area. It is the poorest of Japan's 47 prefectures despite – or, as some critics claim – because of the U.S military presence, and its popularity as a tourist destination. Despite the tiny amount of available land, Japan has for decades overridden local authorities on territorial decisions, most recently in December over the construction of an offshore U.S. military base near the town of Henoko.

Tamaki again implored the Japanese and U.S. governments to ensure the prevention of sexual assaults by U.S. servicemen and demanded greater transparency and timely communication, as revelations emerged that prefectural police and Japan’s foreign ministry had not disclosed multiple assault cases involving the military to his office or the media for months, citing “victims’ privacy”.

Rejecting calls that he was not sufficiently angry, Tamaki said police leadership in Okinawa often came from outside the prefecture and observed a different reporting hierarchy. He said an upcoming visit to Washington would allow him to state the prefecture’s position directly to U.S. officials.

When the assaults did become public, protests were held outside Kadena Air Base, one of 32 U.S. military sites in Okinawa that are home to 25,000 service members and their dependents. Since the 1972 handover, U.S. military personnel have been charged with 6,235 criminal offenses, including 586 violent crimes such as rape, assault, and murder.

Japan says it takes seriously the heavy burden that Okinawa carries with the U.S. military presence, but also calls the prefecture a cornerstone of regional defense, with eyes on potential hostilities in the Taiwan Strait.

The U.S., meanwhile, has expressed deep regret for the crimes, which reached a record in 2023. The Asahi Shimbun, however, noted that U.S. Ambassador to Japan Rahm Emanuel “fell short of apologizing” in recent comments on the allegations.

Some changes may be on the horizon, however.

Some 4,000 U.S. Marines will be transferred from Okinawa to Guam from December in a process expected to take up to four years. According to the Kyodo news agency, the cost is estimated at $8.7 billion, of which Japan will pay up to $2.8 billion. Eventually, the U.S. Marine presence in Okinawa will decline from the current 19,000 to 10,000.

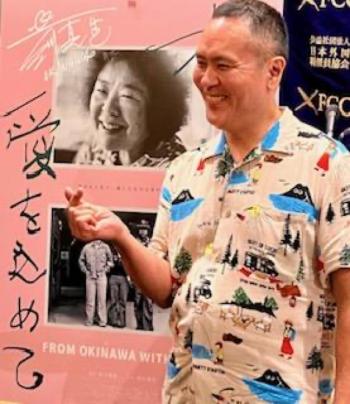

Tamaki’s news conference was one of three Okinawa-related events at the FCCJ last month, including the Gamafuyaa (cave diggers) group, which is protesting the Henoko base development, and a screening of director Hiroshi Sunairi’s documentary From Okinawa with Love.

Takamatsu Gushiken, head of Gamafuyaa, said the Henoko base, which is intended as a replacement for the sprawling Futenma Air Base in the densely populated city of Ginowan, would disturb and dishonor the remains of war dead in the area, Gushiken’s volunteer group has spent decades collecting the multinational remains of those who died in the Battle of Okinawa, and says landfill soil intended for Henoko would inevitably contain those remains.

“It is impossible to completely gather all remains, so this (plan) tramples on the dignity of people in the past war,” Gushiken said. “This is an international humanitarian issue. We are in particular trying to appeal to the bereaved American families to allow them to join in the DNA tests.”

Hiroshi Sunairi

Okinawa was voted Japan’s happiest prefecture in a survey by the Brand Research Institute in 2022, and is considered a Blue Zone, where an inordinate number of people exceed longevity norms.

However, this is not the backdrop to Sunairi’s film, which centers on Okinawa-born photographer Mao Ishikawa, whose works have highlighted marginalized people in the prefecture.

Sunairi said the 71-year-old Ishikawa, who visits the base bar area where she worked and began her career in photography, is a metaphor for the prefecture and a third of his Okinawa Trilogy. In one of the film’s most striking scenes, Ishikawa, ravaged by cancer and wearing a colostomy bag, sits naked in a bathhouse, dripping wet, speaking frankly about her lost youth.

I went to Okinawa last month for the first time in about 30 years. My visit included Mabuni no Oka, home to the Cornerstone of Peace, a historical museum, and the National War Dead Cemetery, which commemorates the estimated 242,000 people who died in the three-month Battle of Okinawa in early 1945.

The site was refurbished for the war’s 50th anniversary, and now has cenotaphs and name identification for every known Korean, Taiwanese, and U.S. soldier who died, as well as Japanese soldiers and Okinawan citizens. The toll is updated every Memorial Day, with some 1,171 names added in the last 13 years.

Unlike some war sites, the Peace Memorial Museum comes across not as a monument for sympathy or rationalization, but rather a place to reflect, treasure peace and the redemptive power of remembrance, and feel both Okinawa’s proximity and distance from the rest of the world.

From its tower, I looked out at the empty beaches and waves and thought of Okinawa’s history, as well as my son, who now lives there and has never directly known war or its consequences. And I took a moment. August is the right time for reflection in Japan.

Dan Sloan is president of the FCCJ. He joined the club in 1994 and previously served as President in 2004 and 2005-06. He reported for Knight-Ridder and Reuters for nearly two decades.