Issue:

The 1964 Summer Olympics changed the landscape and the very soul of Tokyo. Will the 2020 version have the same impact?

The 1964 Olympics, Japan’s startling return to the world’s center stage after the devastation of defeat, celebrates its 50th anniversary this October. Though it was already a favorite hub for many foreign correspondents in 1959, when the host city was selected, the choice of the war-scarred, ramshackle megalopolis over Detroit, Brussels and Vienna struck many as the height of folly, comparable today to picking Qatar as a summer venue for the FIFA World Cup.

Though Tokyo boasted a population of nine million people at the time and was still growing, little more than 20 percent of its residents enjoyed the luxuries of flush toilets, the rest having to be serviced by the ubiquitous “honey trucks” of old gaijin lore. Add to that the dearth of English speakers, the lack of hot water, the bad roads, few hotel rooms and it’s no wonder that foreign observers on the ground were scratching their heads over the IOC’s overwhelming vote of confidence in Japan’s ability to pull off what would have to be the most dramatic urban transformation in Asian, perhaps world, history.

Hours after the IOC’s announcement on May 26, 1959, the Olympic flag was raised in Tokyo, heralding the start of the metamorphosis that turned the ancient city into a gargantuan 24/7 construction site for the next five years. FCCJ members and cohorts were front row witnesses to the unfolding drama.

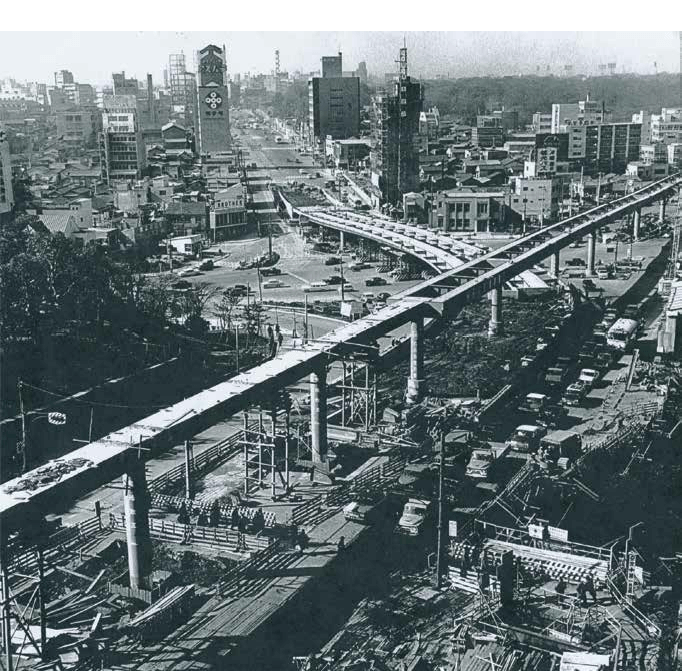

First off the block was the official return to Japan of the Washington Heights property, a 920,000 square meter U.S. military housing complex, to make way for the building of the Olympic Athlete Village. Today the land has become part of Yoyogi Park and the NHK headquarters complex. Its return certainly served to deepen Japan/ U.S. friendship, but must have also been a great relief for some to see the barbarians at the gates of Meiji Shrine finally decamp. Other land was set aside all across Tokyo for the new Shuto Expressway, Monorail, new rail lines and stations.

Then construction went into immediate hyper overdrive.

Bob Whiting arrived in Japan just as noise and air pollution levels were hitting historic heights, and recalls his surprise at seeing oxygen cylinders being sold in vending machines, people overcome by the fumes and electronic boards around the Ginza announcing not only time and temperature, but off the charts carbon monoxide and sulphur dioxide readings.

Many recall the buzz and energy of the time and the excitement of the collective wave of anticipation. But it couldn’t have been much fun for residents who lived over, under, and through those birthing pains. Imagine Akasaka as one of the frenetic hubs of a New Japan in the making. Shuto Expressway going up overhead, infrastructure works beneath. Drills, car horns, blazing lights and action all through the night every night.

Yonetaro Otani watched the urban miracle unfold from his home on the hill, an old samurai mansion with magnificent gardens and moat, which he then converted into the dazzling New Otani Hotel joining the construction rush of the Okura, Hilton and Prince hotels in anticipation of 30,000 foreign visitors. With less than two years to go before the Olympic opening, logistics must have been difficult enough without Mr. Otani deciding after the start of construction that he wanted to add a revolving restaurant on top. His wish that every diner would have a chance to see Mt. Fuji was fortunately realized, though at great effort and additional expense, and the Blue Sky Lounge became an instant landmark. Also helping to meet construction deadlines was the revolutionary all in one “unit bathrooms” 1,085 of which were lifted into place by crane. The finished hotel was a virtual metaphor for overcoming obstacles once thought insurmountable.

Club stalwart Ichiro Urushibara, born in England to a father who had originally travelled to London for the Great Japan Exhibition of 1910, had been forcibly repatriated to Tokyo in 1940 after Japan signed the treaty with Nazi Germany. It felt like cruel fate at the time, but by the 60s, he was a pioneer bilingual radio broad caster. He can still remember the hopeless congestion and noise on the roads as he drove from studio to studio. It didn’t help that parking lots were still rare.

Learning English had become a national mission, and for one of his many hit radio programs at Bunka Hoso, Urushibara penned a “phrase of the day” six days a week to accompany the countdown to the opening of the Tokyo Olympics. He even appeared in a U.S. television commercial for Schlitz beer in which popular American sports commentator Tom Harmon expressed great relief that Schlitz was available in Japan, as Urushibara’s elegant wife, Yuko, made a guest appearance in her kimono, dutifully delivering the cold brew. Never mind that Schlitz wasn't available in Tokyo and they had to put a Schlitz label on a Kirin beer for the scene.

Suddenly, everyone wanted to be seen here, even as the benevolent local bureaucracy found it necessary to ask residents to “Please refrain from urinating on the streets,” or “Do not go to the new Haneda Airport in pajamas and haramaki,” in order not to give visitors a negative impression of Japan.

The total cost of the 1964 Olympics was estimated to be 10 times that of the Rome games in 1960, and that didn’t include most of the Shinkansen construction cost. Five days before the opening, Sports Illustrated magazine highlighted some issues that remained even after an estimated $1.9 billion had been spent to “dress up ugly old Tokyo.”

There are 26,753 cab drivers ready to solve the insanities of the Tokyo address system for English speaking visitors house No. 14 might be next to house No. 13, but it also might be next to house No. 36. Twenty of the 26,753 cab drivers speak English. . . . In Tokyo, some 6,600 athletes will be housed at the Olympic Village, which cost more to build and renovate than was spent on the first nine Olympics together.”

Many think the actual total cost was even higher, equivalent to the nation’s annual budget, but few would debate the spectacular success of the newly democratic Japan’s postwar debut: the world landed at the dazzlingly refurbished Haneda Airport, to a landscape featuring a futuristic monorail (mysteriously dead ending in Hamamatsucho), Tokyo Tower (completed in 1958), Tange’s architectural masterpieces, and on time trains that people could set their watches by. Rikio Imajo, then a photographer working for UPI, remembers making a preopening, mediaonly run on the just finished Ginza-Haneda portion of the Shuto Highway. The ¥50 toll, it was proudly pointed out to him, would be decreased as the cost of construction was gradually paid off, and the elevated road would eventually be free. He is still waiting. Opening Day, Oct. 10, 1964, unfolded under a sky so blue it was as if “the best of the world’s autumn skies have been brought to Tokyo today,” went an oft quoted NHK broadcast. Across that sky, the Blue Impulse acrobatic Self Defense Force pilots created the five magnificent rings that were transmitted to the world via satellite for the first time in Olympic history, all in full color. Yoshinori Sakai, born in Hiroshima on the day the bomb was dropped, and himself a leading runner who had narrowly missed Olympic selection, carried the sacred flame up the stairs to light the Olympic torch. It was an Olympic opening that enthralled the world, and is still remembered by many as one of the best ever.

Domestic television ratings predictably went through the roof, with neighbors and extended families crowding into the few homes fortunate enough to have color televisions. Highest on record was the women’s volleyball final, in which the Japanese “Witches of the Orient” beat the Russians. Americans did exception ally well. Gene Saltzgaver, who had just left the Far East Network and was helping to cover the games for the Asahi Evening News, remembers that the “Star Spangled Banner” was Japan’s most popular song in the autumn of 1964. The U.S. flag went up so often that all of Tokyo seemed to be humming it even a Japanese copy boy in the AEN newsroom, who was whistling the tune rather loudly to the great amusement of everyone on the news desk.

Abebe Bikila, already a living legend after his barefoot gold medal marathon in Rome, defended the title in convincing fashion, and was arguably the most venerated athlete of 1964. All of Japan fell in love with the graceful Vera Caslavska, the all round gold medalist who represented the end of the age when gymnastics was more elegant ballet than the teenage acrobatics it has since become. Dutchman Anton Geesink won the gold in judo’s open weight division the first time it was contested in the Olympics. The shock to the nation’s psyche in what many thought was an unlosable sport, was deep, but that soon was replaced with profound respect and affection for Geesink, which was never forgotten.

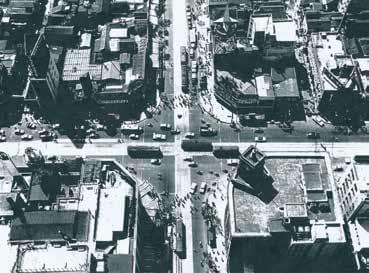

Ginza crossing in 1958

Ginza crossing in 1962

There were future legends galore: Joe Frazier arrived as a reserve and ended up winning the heavyweight boxing gold, going on to become heavyweight boxing champion of the world and creating the sport’s Golden Age with Muhammad Ali. Bob Hayes easily took the 100 meter sprint gold in borrowed shoes, then came from five runners back to propel the U.S. team to a 4 x 100 gold in what still may be the fastest relay split ever run, including Usain Bolt’s time at the 2012 Olympics. And it was run on a wet, ripped up cinder track, no less. (Bullet Bob’s speed took him to a Super Bowl ring with the Dallas Cowboys and into the NFL Hall of Fame, revolutionizing the entire game of American football in his wake.) Future Japan national soccer team manager Ivica Osim was on the pitch as a young standout for Yugoslavia.

Former Business Week Bureau Chief and FCCJ president Bob Neff was a 17 year old senior at the American School in Japan, who headed to the Olympic stadium with his friend after they learned NHK wasn’t going to televise the men’s basketball final. Of course, all tickets were sold out, but bemused guards and officials pretended to believe Neff’s story of them having just arrived from Haneda and not being able to find their tickets. Neff watched the finals shoulder to shoulder with basketball dignitaries and VIP guests. On the floor that night leading the U.S. to another gold was Princeton star Bill Bradley, who was to go on to win two NBA championships with the Knicks and three terms in the U.S. Senate.

The most prolific journalist perhaps, was the Club’s own Vivienne Kenrick, a popular interview columnist at the Japan Times. While covering the games for AP, Reuters and the Japan Times, she was also the local liaison officer for the British equestrian team, keeping an eye out for the well being of officials, athletes and horses. Apart from daily filings through out the equestrian events, her daughter Miranda recalls Vivienne writing a dozen stories in the lead up, and perhaps just as many immediately after the Games including interviews with a barrage of medallists and a full spectrum of Olympic luminaries, like then JOC chairman Prince Tsuneyoshi, father of the current JOC chairman. Miranda can still remember the dizzying energy she felt as she watched a gray town magically transformed into an international hub pulsating with Japan’s new glamour and sightings of the world’s top athletes.

Kenrick wasn’t the only one looking after the British sports mission. Chris MacDonald, widely recognized for his role in helping raise Japanese soccer to world standards and a Japan Soccer Hall of Famer, looked after the young arrivals while running around preparing Japanese soccer officials and refs, who had little experience in world class tournaments. He even took to the microphones for the Olympic matches.

Renowned dentist Dr. John Besford, himself a two time Olympic swimmer, was “uncle” to the swim team and took the whole group for a break at his beachfront villa. Perhaps the Olympic Village food was a tad too posh for the home sick swimmers. Asked what they wanted to eat, he was bemused by their collective call for ordinary “toast!” and promptly sent out for six toasters, which were then scattered throughout the house, as there wasn’t enough voltage in any single outlet to power the appliances.

Besford’s trusted assistant, Teruko Fukasawa, was seconded to the British delegation headquarters in the Village as an interpreter, and recalls the wonderful camaraderie and excitement that permeated Tokyo through out the entire Games. Besford’s dental practice was at the center of Tokyo’s expatriate life, so unlike most Japanese at the time she was familiar with the celebratory traditions and drinking customs of Europeans.

But she is still laughing at just how much scotch and gin were consumed in the headquarters’ lounge upstairs at the former U.S. Air Force residence. “Every day there were occasions which war ranted multiple trips upstairs, whether it was a medal, a qualifier, or even a disappointment,” she says. “I remember being surprised at the number of cases [of alcohol] which came in the delegation’s cargo, plus a huge supply of tonic water, which apparently wasn’t available in Tokyo.”

The food on offer during the Olympics was of extraordinary gourmet standards and presentation at a level never experienced in an Olympic Village before or since. Japan showcased its very best to press, visitors and athletes alike, and the reaction was the start of the world’s love affair with Japanese food and food culture. Never mind the visitors’ bewilderment over Japan’s favorite offerings of mysterious “Viking Food” and “snails” (sazae). The Imperial and New Grand hotels led teams of the nation’s best known chefs running four 24 hour restaurants on the premises, something the athletes still rave over today.

AP PHOTO/N.MASAKI

Olympians were equally impressed by a range of firsts, including the full computerization of results by IBM and electronic timing by SEIKO. In fact, the Tokyo Olympics are remembered by many as the first time finishes weren’t endlessly contested. Long jump gold medalist Lynn “the Leap” Davies, now president of UK Athletics, has been to nine Olympics since 1964. Even from his privileged, multi faceted vantage point, the Tokyo Games were the only ones that rate alongside the London Games of 2012 as the absolute best. He remembers the thoughtfulness of cleaning staff who wore masks to protect athletes against infection, and bicycles that were freely distributed and could be dropped anywhere in the Olympic village at the athletes’ convenience. It took a few times of missing the shuttle bus for foreign athletes to realize what “on time” meant in Japan such was the clockwork precision of everything in the Village.

Held in October to avoid the swelter of August and typhoons in September, Tokyo 1964 was one of the coldest Summer Olympics ever on a par, ironically, with the average temperatures at the recent Sochi Winter Olympics. So cold, in fact, that Davies chuckles as he recalls rather modestly that it may have given UK athletes, used to training on cold, rainy tracks, a big advantage. No such luck should be anticipated for the next Tokyo Games, to be held from July 24 to Aug. 9. Tokyo’s biggest omotenashi challenge in 2020, in fact, may be none other than to keep athletes and spectators alive in midsummer conditions. As host cities now have little voice in the choice of dates, the next Tokyo Olympics are on course to becoming the hottest ever.

COURTESY OF BILLY MILLS

Billy Mills is one who has no doubt Japan will deliver another memorable performance. His love affair began the day he arrived in Tokyo, and was enhanced, of course, by his gold medal in the 10,000 meters. It was a historical performance still considered one of the most exciting finishes in Olympic history, competing, as it was, for space on the front pages of the world’s newspapers on the same day as the equally dramatic ouster of Soviet premier Krushchev.

On his last day in Japan, Mills went to the U.S. motorpool to arrange transportation for him and his wife, Patricia, to the airport, only to be told that all vehicles assigned to the team were being used by officials for sightseeing for the rest of the day and that he should find his own way to the airport. Mills apologetically approached the Japan Olympic Committee desk to ask for help. He had just paid a rather large sum of money to check Pat out of the Palace Hotel, where she had been staying throughout the Olympics, and had no cash left to pay for transportation.

Something may have been lost in the translation, but the officials looked aghast, and started running around with great urgency. The next thing they knew, Billy and Pat were being shown, with profuse apologies and deep bows, into a glittering limo, and to their eternal surprise, seen off with great ceremony in a full motorcade.

“Only in Japan,” many still say with awe today. May the same omotenashi spirit guide the world to fall in love with Tokyo all over again in 2020.