Issue:

May 2025

Remembering the first Osaka Expo, 55 years ago

(First of two parts)

In September 1969, three months after graduating from Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, with a baccalaureate in Asian Studies, I arrived in Taipei, Taiwan for postgraduate studies in Chinese at Taiwan Normal University.

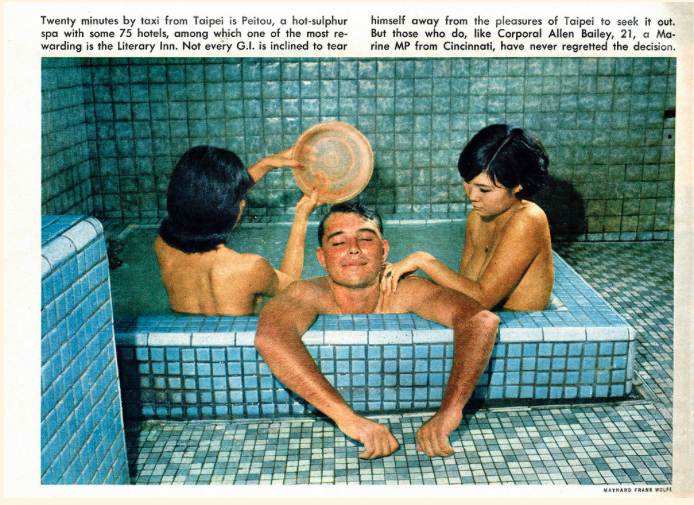

I recalled an article in Time magazine several years earlier, while I was living on Okinawa, that showed an American soldier on R&R leave from Vietnam receiving exceptionally attentive service at the Literary Inn, a gracious old Japanese-style hotel in Peitou, a Taipei suburb popular for its mineral hot springs.

I researched the hotel's name in Chinese – purely out of curiosity, you understand - and hopped aboard the Number 11 Guanghua bus to Peitou to investigate.

The Literary Inn's operators turned out to be two sisters from Xiamen (Amoy) who were both devout Christians. I befriended Mrs. Zhou, the widow of the hotel's founder, who asked me to give English lessons to her adult son, who had a rare skeletomuscular disorder.

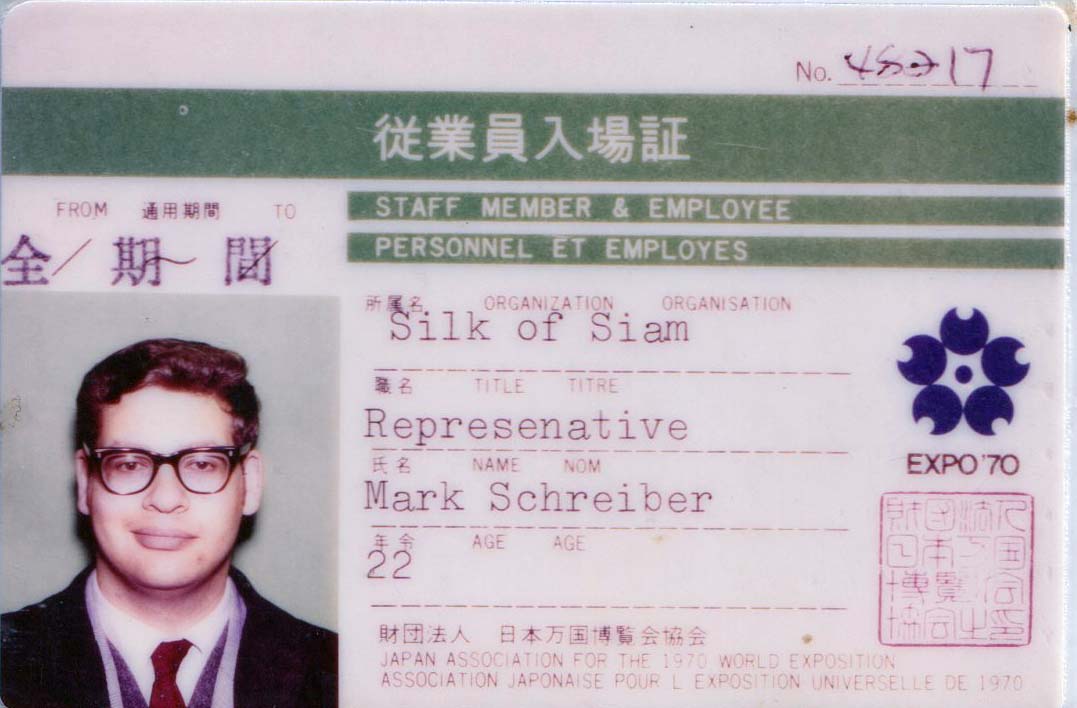

One afternoon in early January 1970, I was just winding up a lesson at the hotel when an American guest at the hotel overheard us conversing in Japanese. His curiosity piqued, he began firing questions at me. His company, he explained, had won the bid to represent Thailand at the International Bazaar at the Osaka Expo, due to open in about two months.

He was Peter B. Forgham, an American who billed himself as the "New Thai Silk King," heir apparent to the original silk king, Jim Thompson.

During World War II, Thompson, scion of a Delaware family involved in textile manufacturing, had served as an operative in the OSS, forerunner to the CIA. He remained in Asia and went on to establish The Thai Silk Company Limited in 1948.

From 1951, Thai silk gradually began to attain an aura of glamor in Western countries when it was used for performers' costumes in the Rogers and Hammerstein musical The King and I. As a result, Thompson's silk business took off. With his earnings he built his dream home, a traditional wooden house made out of Thai teak, which he decorated with antique ceramics and other objets d'art. Even today, the Jim Thompson House remains a popular destination for visitors to Bangkok.

In March 1967, Thompson's luck ran out. While on a visit to Malaysia, he disappeared without a trace. (He was declared dead in absentia by a Thai court in 1974.) Soon after his disappearance, another American, Peter Forgham, stepped up, determined to fill Thompson's shoes. When people occasionally joked that it was probably Peter who had arranged for Thompson's disappearance, Forgham did nothing to disabuse them of the idea.

After serving a stint in the U.S. Coast Guard on Guam, Forgham vowed he would never work at a salaried job again, and kept that promise until his death in Mexico in 2009 aged 69.

With the Vietnam War in full swing by this time, opportunity knocked, and Peter, backed by several investors, started a company he named Silk of Siam to supply the U.S. military exchange system with Asian handicrafts and jewelry.

Peter was given to indulging in colorful hyperbole. Once I asked him why, during his time in the Coast Guard, he had never been tattooed. "I decided that if I didn't have a million dollars by the time I was 30, I would turn to a life of crime," he replied. "And I didn't want to have any identifying marks."

Age 30 at the time of the Expo, Peter stood 190 cm (6'3") tall, with massive shoulders and torso, along with an equally gargantuan ego and a hair-trigger temper. He also had an insatiable libido, and once made a bet that he could get laid within 30 minutes of exiting the arrivals terminal at Bangkok's old Don Muang airport. (He claimed to have won the bet.)

The night before Peter departed Taipei, we went to the snack bar in the U.S. Navy compound on Chungshan North Road. While sipping milkshakes – he was a lifelong teetotaler – he proposed that I manage his shop at the Osaka Expo. I agreed. I was not given a written contract to sign, but Peter exacted two verbal promises: one was to never go into competition with him in the silk business; the other was to steer clear of the attractive young models he had hired to work in his shop.

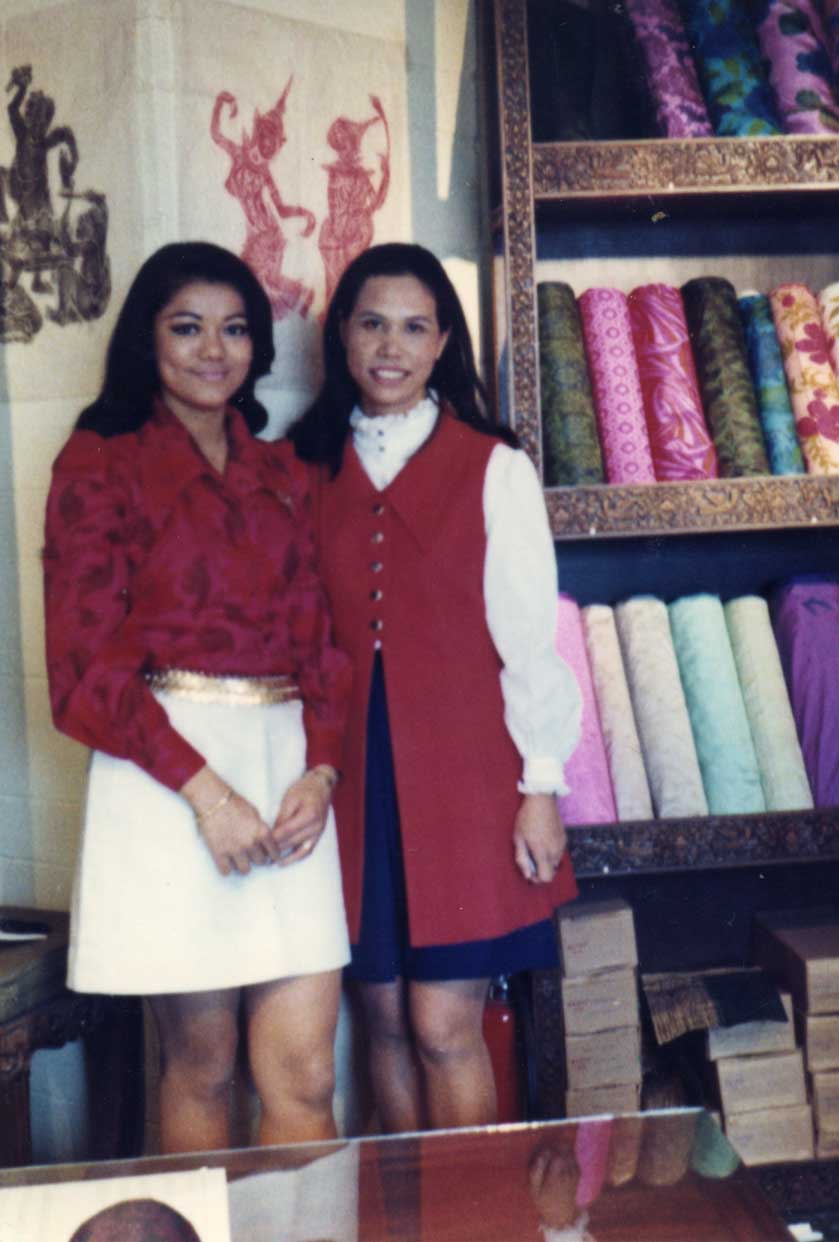

Those models lived up to their billing. One was Tan Hong Eng, aka Lucy Tan, a Singaporean who, under the nom de guerre of Philomena Tan, was reputed to have been the first ethnic Chinese woman to appear nude in America's Playboy magazine, in the December 1968 Women of the Orient edition.

On March 6, I departed Taipei aboard a Thai International Boeing 707 bound for Osaka's Itami airport. As I headed for the taxi stand outside the international arrivals terminal, a light snow was falling.

Since the Expo was scheduled to open on March 15, we had just over one week to get the store stocked with merchandise and open for business. Accompanying Peter were Lucy Tan and five other English-speaking models he had recruited from Thailand, Singapore and Hong Kong. They all spoke passable English, and the two Singaporeans in particular could curse like sailors.

Functioning as mother hen to keep the women in line and repel potential suitors was Peter's elderly Thai housekeeper Boonsom, who communicated in a colorful mixture of English, Thai and Hokkien Chinese.

None of our foreign store staff had ever been north of the Tropic of Cancer, and for their first six weeks in Japan they constantly complained about the cold weather.

While the women shivered in their hotel rooms, Peter obtained the keys to two semi-furnished apartments at Higashi-Machi in Toyonaka, a short walk from the Senri Hankyu Hotel. The apartments were built in the danchi (public housing development) style prevalent in Japan in the 1960s, which meant a walkup to the fifth floor, where I stayed. Our building was C-26, which we shared with South Vietnam and several other contingents. The U.S. pavilion staff had the entire C-23 building to themselves. Three of the U.S. pavilion guides living there – Caryn Callahan, Beverly Grey and Rusty Lavelle – had been my classmates at International Christian University in Tokyo just a few years earlier. We saw a lot of each other at the Expo.

The next day, Peter and I went to the Hanshin department store in front of Umeda station, and after haggling for a volume discount, placed an order for electric space heaters, bedding, cooking utensils, tableware, and other household items. At the time, prices in Japan seemed incredibly cheap as the exchange rate was still pegged at ¥360 to $1.

We then went to the Expo Association office to apply for entry passes, and began work on the shop. Peter and I laid down a durable indoor-outdoor carpet while a team of Japanese workmen assembled the jewelry display cases, merchandise shelves and other fixtures. An electrician came to install spotlights – which turned out to be a serious mistake as the heat they generated turned the shop into a veritable sweatbox when summer arrived.

The 330-hectare Expo site was bifurcated by a dedicated rail station on Osaka's Namboku Line, with Taro Okamoto's Tower of the Sun and the foreign and domestic pavilions on the station's north side, and the International Bazaar and the Expoland amusement park to the south. Expoland would remain in operation for nearly 40 years, until declaring bankruptcy in February 2009.

Along with tacky souvenirs and thrilling roller coaster rides, the International Bazaar and Expoland featured some decent restaurants. Michael Kleber managed Munich House, a German beer hall that featured a live band, Lowenbrau draft beer, and tasty bratwurst and rosti. Pacing outside the Indian restaurant was a turbaned Sikh greeter, a burly pro wrestler named Singh, who willingly posed for photos with visitors as he chanted the restaurant's menu mantra: "Hai, doooooo-zo! Chicken curry, beef curry, egg curry, prawn curry ... ichi ni no san shi, yatta ze Kato-cha!"

Weeks passed and the chilly spring weather eventually gave way to the Osaka summer, which was steaming hot by day and sweltering by night. Sounds frequently heard above the normal Expo cacophony were the sirens on ambulances summoned to treat visitors who had collapsed from heatstroke. During the August vacation season, getting into the U.S. pavilion to see an authentic moon rock brought back to earth the previous year by Apollo 12 – the second moon landing – often required standing under a blazing sun for five hours.

The demands of my job left scant time to familiarize myself with Osaka. On weekdays I took the train into the city, where I enjoyed strolling up and down the covered shopping street in Shinsaibashi. To escape the summer heat, I spent the occasional free afternoon in air-conditioned movie theaters in the Namba and Umeda areas. I also developed an appreciation for Osaka-style sushi, especially negitoro-maki (fatty tuna with chopped leeks wrapped in seaweed) and anakyu-maki (conger eel with cucumber) – flavors that I had not experienced in Tokyo. Korean barbecue at the Daidomon restaurant, which had just opened two years earlier, could be counted on to satisfy my most carnivorous cravings.

The 1970 Osaka Expo boasted the distinction of being the first world exposition to be held in Asia. Over its six months of operation, a total of 64.2 million people – roughly equivalent to half of Japan's population – would visit the site, setting a record for attendance that was not surpassed until 73 million visited the Shanghai World Expo in 2010. Projections for attendance at this year's Osaka Kansai Expo are considerably more modest.

To be continued ….

Mark Schreiber met his wife-to-be at the 1970 Expo and says one exposition is enough. He has no plans to visit the 2025 event.