Issue:

May 2025

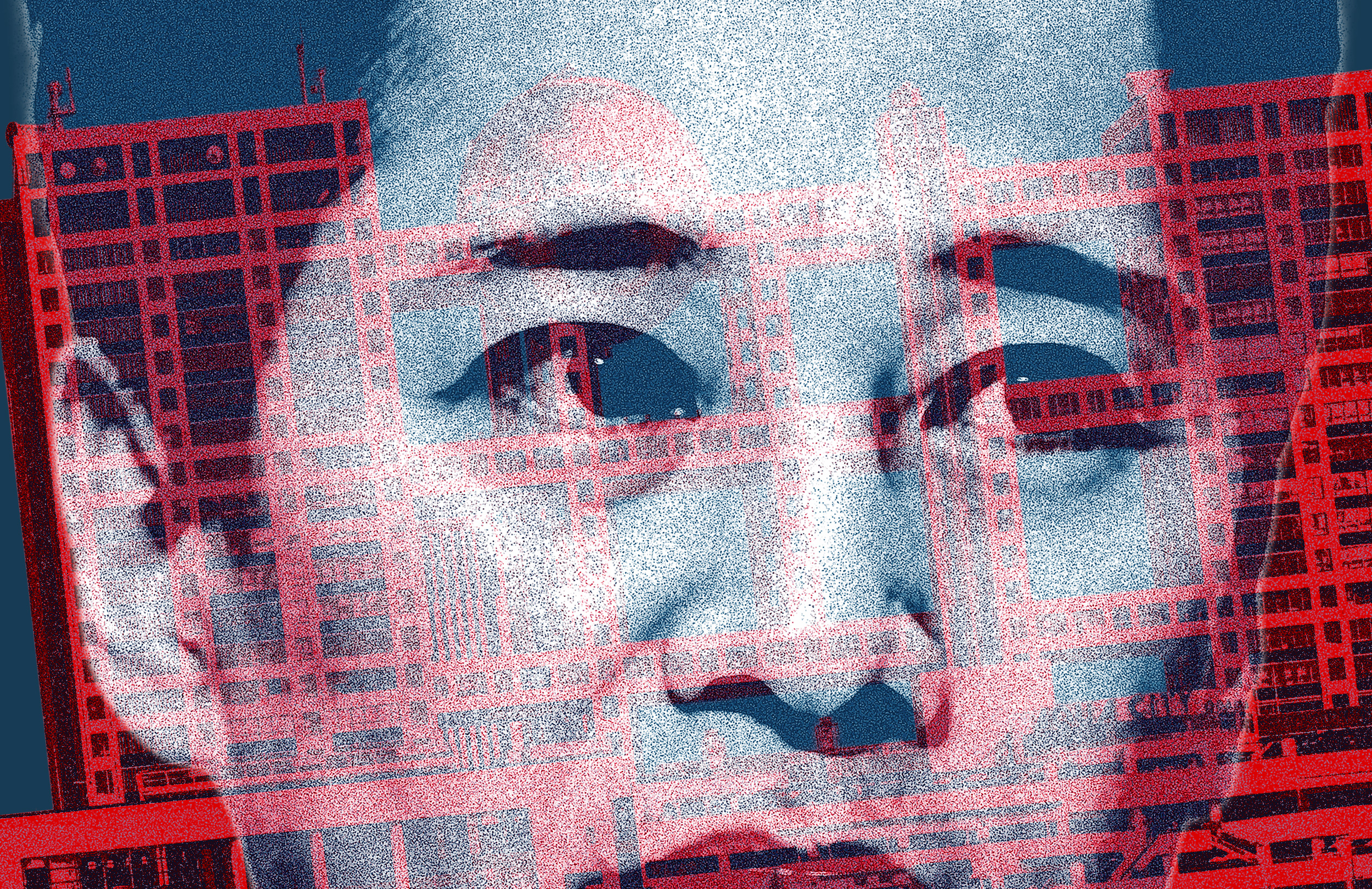

Sexual assault scandal exposes the treatment of women in broadcasting

How to sum up the Masahiro Nakai-Fuji TV saga?

Perhaps by saying that it is a mixture of the worst practices of the Japanese media. Not only because it took place inside a far from exemplary private television channel, but also because of the way the public has been informed about it by the press.

It all began, as it often does, with a series of articles published in the weekly magazine Shukan Bunshun. Masahiro Nakai, a former member of SMAP, was accused of assaulting a Fuji TV employee during a private party. He has also been accused of paying her compensation so that she would not reveal what had happened to her.

The facts are not recent: they date back to the summer of 2023, but nothing had emerged in the interim. From the beginning, it was clear from reading media reports that the “trouble” referred to was probably a sexual assault.

The articles also explained that Fuji TV officials had been made aware of the matter, but chose to protect their business and avoid tarnishing Nakai’s image. After all, before the claims, he brought the broadcaster attention, sponsorship and money.

The first press conference held by Fuji TV's bosses after the Shukan Bunshun revelations was fully in line with this strategy: a small room, no cameras, no sound recording, and a limited number of press club journalists who usually attend the chairman's regular press conferences.

The arrangements made a mockery of the media's role. And it was handled with disconcerting amateurism. The public broadcaster NHK, which found itself in the unusual position of being excluded from the press conference, criticized Fuji TV. This was laughable, given the extent to which NHK generally contributes to protecting the kisha club cartel. But when NHK is among the victims, the system is suddenly unfair. Perhaps this was the only bright spot in an otherwise depressing affair.

The first press conference held by Fuji TV's directors ended with outcry from other media organizations. In response, the company held a second presser that was open to all media and with no time limits. The result was chaos of a different kind: hundreds of journalists attending an event that lasted an incredible 10 hours. I left after an hour and continued to listen in via YouTube for three more hours until I gave up on this pointless exercise.

After almost all of Fuji TV’s sponsors decided to withdraw their support – and a major foreign shareholder publicly criticized its conduct – the broadcaster entrusted a group of lawyers with conducting an investigation.

According to their report, “Nakai committed what should be recognized as a sexual assault not in a private context, but as an extension of a professional relationship, with a hierarchical relationship that placed the girl in a position of inferiority.” The lawyers said sexual harassment was not uncommon at Fuji TV and cited several other examples.

The report was excoriating, but the handling of the case was riddled with errors, inconsistencies and paradoxes. If Nakai had committed a crime, as the lawyers' report suggested, surely the police should investigate – a natural progression that was not mentioned in media coverage. If the woman had not sued Nakai, it might have been because she had been dissuaded from doing so, in particular by receiving a considerable sum of money from him. Still, the lack of police involvement is puzzling.

By withdrawing advertising and sponsorship, companies were seeking to condemn Fuji TV and harm it financially, but they also punished the broadcaster’s many employees who had no connection to the scandal.

The current situation, in which a reference to a sexual assault has not been followed by a criminal investigation, is dangerous and troubling.

On a personal note, I was once invited to take part in a morning “wideshow” on Fuji TV. The fee I was offered gave me pause for thought. For a few minutes of commentary on the programme, I could have earned more than I would reporting on the radio for an entire week. And I was probably not being offered nearly as much as other contributors. For me, it was evidence that sections of the media inhabit a bubble that is detached from the lives led by their viewers. In that sense, it is hardly surprising when - as in the case of a sexual assault by a prominent entertainer - they end up falling short.

Karyn Nishimura is a correspondent for the French daily newspaper Libération and Radio France.