Issue:

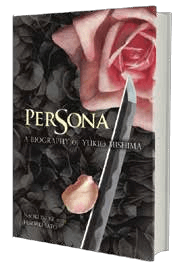

BOOK REVIEW PERSONA: A Biography of Yukio Mishima

By Naoki Inose and Hiroaki Sato (Stone Bridge Press, 2013)

reviewed by Andrew Pothecary

What would Yukio Mishima individual, clown, actor, imposter, gangster, or aristocrat, as theater producer Nobuko Albery once described him in a BBC arts program make of today’s Japan?

It’s an unanswerable question, but one that rears its head when reading the new biography, Persona. If the LDP in power, questions about Article 9 of the Constitution, Shintaro Ishihara’s “emotive activism” creating a sense of political crisis, and an awkward Japan-U.S. relationship all sound familiar, it’s not far from the political landscape of 40 years ago, when Mishima committed seppuku after a doomed attempt to incite the SDF to rebellion and to reinstate the rule/role of the emperor.

Persona’s original Japanese version was an analysis of Mishima in relation to the politics and society in which he was born, lived, worked and acted, written by current Tokyo governor Naoki Inose in 1995. This new English edition is not simply a translation; it has been embellished with a study of Mishima’s “literary, theoretical and ideological theories and activities” by Hiroaki Sato.

As to that ideology: Mishima still suffers a nomenclature that includes the term “fascist,” but Persona as did Marguerite Yourcenar’s Mishima: a Vision of the Void reveals why it doesn’t fit, while never shying away from analysis of his rightwing ideology.

I started reading Mishima at school and continued even after I became involved in anti fascist campaigns. So how do I explain or justify my admiration of the work and the man with such seemingly opposing views?

I am not alone. Persona has a reassuring passage about Mishima’s final interview with a Marxist literary critic whose questions “were not just probing but frequently antagonistic.” In the end, the critic admitted being told once by another author after attacking Mishima, “If you like Mishima so much, come right out and say it. That would make your argument more logical.” And the critic acknowledged that it was true.

If Mishima were merely a purist and right winger, he would of course be dull to all but fellow travelers. It’s the constant paradox that makes him interesting. Persona, in its detail and length, does a fair job of getting behind the multiple contradictions. His bisexuality, in fact, often more clearly expressed in his fiction than declared in his lifetime, is only one more “double” aspect.

The married Mishima’s adult homo sexuality is broached early but hesitantly. Insose asks, “Was Mishima exaggerating or in some way faking his homosexual tendencies?” Fortunately, his question seems rhetorical, and the authors employ more and occasionally explicit examples of the reality. But if obfuscation remains, it wasn’t helped by Mishima himself: a month before he died, he is quoted as saying, “Hmm. I wonder if I have some homosexual elements in me, though I do not think I’m homosexual…”

Good grief, he wondered!? His sexuality was complex, but this statement was, of course, disingenuous, especially considering that it was the same month he discussed a limited edition of Confessions of a Mask that would have a glass cover to indicate that the supposedly “masked” narrative was, in fact, plainly autobiographical.

A THIRD BIOGRAPHY

What does the book bring to English language readers that FCCJ member Henry Scott Stokes or John Nathan didn’t cover in their biographies? Scott Stokes’ book remains perhaps the introduction to Mishima, with its journalist’s research and insights from his friendship with the author. Persona is a work of greater research and analysis with benefit of 20 more years of research and Sato’s further additions and is a great find for Mishima readers who want to be taken further into the work and his context. It also has some extracts that haven’t been available in English. (Note to publishers: if there’s a market for another biography, surely there is also one for not yet translated works for a start, his epic Kyoko’s House.)

There are quibbles. Some of the text could have done with an extra round under an editor’s eye. Although this seems to improve after the early pages, it remains noticeable in translations of quotes from the man or his books. Though Sato has translated Mishima (the novel Silk and Insight) in the past, his retranslation of the poem “Icarus” is an example. The published translation by John Bester includes the two flowing lines, “Is the blue of the sky like a dream/Was it devised by the earth, to which I belonged…” Persona clumsily has it: “Was everything what the earth where I belonged schemed/The blue of the sky a hypothesis…”

BACK TO TODAY

Mishima died disappointed in a modernizing Japan after a life infused with inklings of death. But while the political situation noted above remains, it’s impossible to imagine Mishima living now. The book quotes him in 1970: “I am deepening my sense every day that, if things continue as is, ‘Japan’ may cease to exist. If it does, there may remain in its place, in one corner of the Far East, a great economic power that is inorganic, empty, neutral, intermediate color, wealthy, and shrewd.”

We may not need the mortal cut that Mishima prescribed for himself, but even without sharing his ideology, one might wonder if his fears were justified.

Andrew Pothecary is a freelance designer and art director of Number 1 Shimbun. His design work name Forbidden Colour is partly inspired by Mishima.