Issue:

DAVID BOWIE AND JAPAN

The instrumental “Moss Garden” features Bowie playing the koto

On “Heroes,” 1977, and inspired by a visit to Saihoji in Kyoto

“I don’t know why he was so attracted to things Japanese, but perhaps it wasn’t so much Japan or Japaneseness itself. He knew when he looked good in something.”

Kansai Yamamoto, clothes designer,

BBC News website, Jan. 12, 2016

He also sometimes wore a kimono inspired cape with traditional Japanese characters on it which spell out his name phonetically, but also translate to

“FIERY VOMITING AND VENTING IN A MENACING MANNER”

About

10,200,000

Google search results for “David Bowie Japan”

“A world in which David is not living still feels totally unreal.”

Miu Sakamoto, daughter of Ryuichi Sakamoto, Twitter, Jan. 11, 2016. Miu meets Bowie in the photo she tweeted, left.

俺の頭に弾 を打ち込めば 新 聞は書き 立 てる

“Put a bullet in my brain and it makes all the papers”

Lyric spoken in Japanese, “It’s No Game, Pt 1,” Scary Monsters and Super Creeps, 1980

“I wanted to break down a particular type of sexist attitude … the ‘Japanese girl’ typifies it, where everyone pictures them as … very sweet, demure and non-thinking, when in fact that’s the absolute opposite of what women are like. … I wanted to caricature that attitude by having a very forceful Japanese voice on it. So I had [actress Michi Hirota] come out with a very samurai kind of thing.”

David Bowie about “It’s No Game, Pt 1,” quoted in The Man Who Changed the World, by Wim Hendrikse

The two of us were sitting at the bar by the beach … when an attractive young woman passed by [and] exclaimed,

“OH MY GOD, I DON’T BELIEVE IT. IT’S ROGER PULVERS!”

I was the one who couldn’t believe it, and Bowie . . . gave out a hearty laugh. . . . “That was wonderful,” Bowie said, turning to me and smiling generously.

“JUST ABSOLUTELY WONDERFUL.”

Roger Pulvers remembering a break with David Bowie during the filming of Nagisa Oshima’s Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence,

the Japan Times, Jan. 14, 2016

SEIDENSTICKER SENSEI

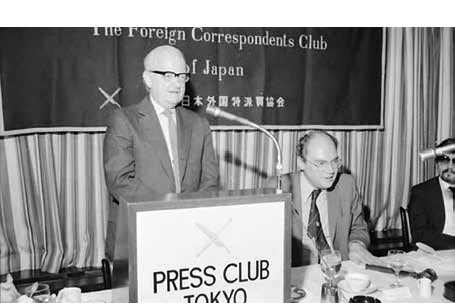

At a professional luncheon on April 27, 1983, noted translator, author, and Japanologist Edward G. Seidensticker expanded on his recent book, Low City, High City: Tokyo from Edo to the Earthquake. He also detailed some of the intricacies of converting Japanese literature into an interesting read in English while remaining true to the spirit of the original. Seated next to him is then-president Karel van Wolferen (NRC Handelsblad), who himself would soon become famous for his controversial book on Japan, The Enigma of Japanese Power. Partially visible next to him is Richard Pyle, a veteran AP correspondent noted for his coverage of the Vietnam War, who had re-energized journalistic discussions in the Main Bar after being assigned to Tokyo in 1980.

Edward Seidensticker became well known for his deft translations of Japanese literature, both modern and ancient. Translations of works by Kawabata Yasunari, particularly Snow Country (1956) and Thousand Cranes (1959), led to Kawabata winning the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1968. During the same time frame he also translated two books by Tanizaki Junichiro, Some Prefer Nettles (1955) and The Makioka Sisters (1957), and then In Praise of Shadows (1977) two decades later. Equally well known are his translations of the Heian-era Kagero Nikki, which he rendered as The Gossamer Years (1964), and the exceedingly difficult Tale of Genji (1976).

As an author, Seidensticker followed up Low City, High City with a second book, Tokyo Rising: The City Since the Great Earthquake (1990), that continued his history of this great city. (Both volumes were combined into one in 2010, with a preface written by his old friend, Donald Richie.)

Seidensticker, born in 1921 in Colorado, was a graduate of the University of Colorado (1942) where he also studied Japanese at the U.S. Navy’s Language School. Following service as a language officer with the U.S. Marines during WWII and a stint in Japan as a translator, he obtained a master’s degree from Columbia University before going on to study Japanese literature at the University of Tokyo.

Seidensticker was also an educator. And as one of his former students I can report that he was a good one, with a sense of humor. His course, “The Cultural History of Japan,” was quite popular at Sophia University at the end of the ’50s and early ’60s. Those years were no doubt a good warm up for his later teaching positions at Stanford, University of Michigan, and finally Columbia, from 1978 until retirement in 1985.

After retirement, he divided his time between Japan and Hawaii (where it was again my good fortune to meet him at a house party in Honolulu in 2003 and review the good old days at Sophia).

He died in 2007 following a fall while on his customary stroll around Shinobazu pond in Ueno. A head injury eventually led to his death in a Tokyo hospital at the age of 86. Among the honors he had received over the years was one of the Japanese government’s highest, the third-class Order of the Rising Sun, for his work in introducing Japanese literature to the outside world.