Issue:

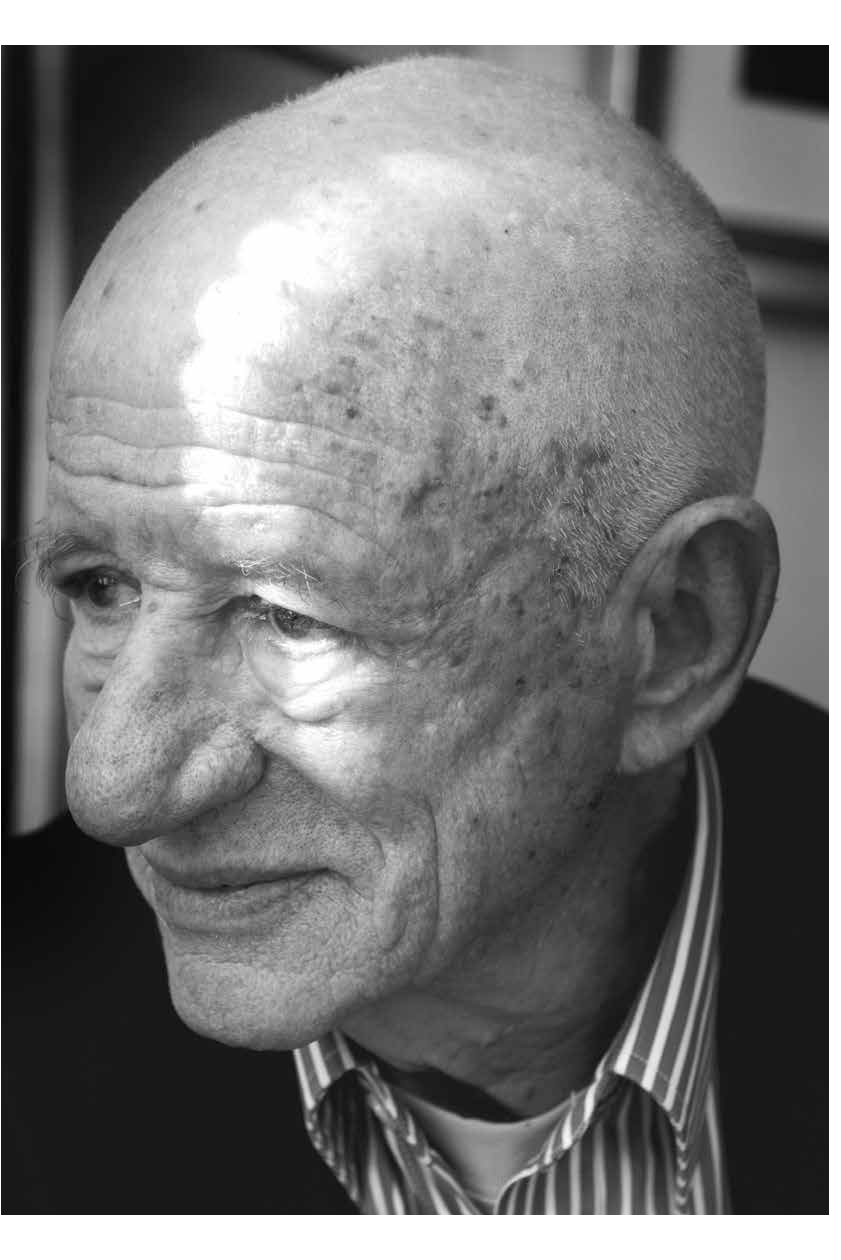

Gregory Clark

It was 1964, I was sitting in the middle of the Kremlin around the green baize table; on the other side was Kosy- gin, the premier, and Gromyko, the foreign minister. On our side was the Australian foreign minister, Hasluck.”

An interview that kicks off in that fashion would seem to suggest an eventful career and some good yarns; Gregory Clark qualifies on both counts.

After graduation from Oxford University (he was accepted at 16) and some adventures in Europe, Clark headed back home to Australia in 1956 to begin a diplomatic career in the Department of External Affairs. It was to include a year of Chinese studies in Hong Kong, which would help stimulate a long fascination with Asia.

After a couple of years as the China Desk officer in Can- berra, he was posted to Moscow, where the Kremlin meeting above took place after the Australian foreign minister “arrived demanding a meeting with the top Soviet leadership for whom he had an urgent message.”

The message contained what Clark describes as not only a misunderstanding of geopolitics in inviting Russia to join the Vietnam War to stop China – which Canberra believed was pulling the strings – but of basic geography, mistakenly identifying the province of Sinkiang as Russian territory coveted by China.

“The Russians were amazed,” says Clark, and after correct- ing the visitors’ geography, they informed the Australians that they would support the “brave struggle of our Vietnam- ese comrades against American imperialism, and wished the Chinese would do more to help.”

After resigning in disgust at what he saw as ignorance about the Vietnam War, in October 1964, Clark was offered the chance to express his views on Vietnam in Rupert Mur- doch’s newly-launched news-paper. “People forget, but the Australian was a very progres-sive newspaper at the beginning, launched by Murdoch to oppose the Vietnam War.”

The article detailed what Clark believes was the myth that the conflict was caused by Chinese aggression. Finding outlets for his contrarian view on China dif-ficult to come by, he took a year off from his studies to write a book on the subject. The research for In Fear of China brought him to Japan, where he would meet his wife and future mother of his two sons. Translated into Japanese after it was published in 1967, it later opened doors for him in the country.

OFFERED THE CHANCE TO launch the Australian’s Tokyo bureau in 1969, which also began his long FCCJ membership, Clark was sent for a two-month journalism crash course at the paper’s HQ. There he witnessed a pivotal episode that Clark says helped change Murdoch from a liberal to a scourge of the left.

“For national news, the plates were prepared in Canberra, and had to be flown, or driven if there was fog, to Sydney for printing. The print unions knew this. So sure enough, come five o’clock in the afternoon, a demand would come through, threatening a 24-hour strike.”

“You could see the look on Murdoch’s face: ‘If this is what they do to the one progressive newspaper in Australia, to hell with the unions.’ ”

The reporters and management, including Murdoch, would have to go down and lay out the type themselves, a labori- ous and messy process in those days. “You could see the look on Murdoch’s face as he did this: ‘If this is what they do to the one progressive newspaper in Australia, to hell with the unions and the left wing.’”

Setting up the paper’s bureau on the sixth floor of the Nik- kei’s building turned out to be serendipitous, as Clark was able to see the Japanese business daily before it was put to bed. His Japanese reading ability, which he says was already an advantage over his Australian rivals, was now put to use scanning for stories.

After what he calls “four great years at the Australian,” and a year back in Canberra working for the government, Clark was approached in the 1970s to write a book for the Japanese market. “The Japanese were getting very curious to know how the rest of the world saw them.”

Clark already had an idea for a book about why the Japanese and Chinese were so different. On delivering the manuscript, the publishing company boss gave it the title The Japanese: Origins of Uniqueness, although that wasn’t really its theme, recalls Clark.

THE TITLE DID GENERATE enough publicity to sell the book, and more importantly, made Clark a fixture on the corpo- rate lecture circuit. He spent the next 20 years being paid handsomely for 90-minute talks on the theme of “Japanese uniqueness” to audiences across the country a few times a week. The higher profile also boosted his career at Sophia University, where the faculty upgraded him from visiting lec- turer to full professor.

The lucrative lecture gig came to an abrupt end when the Sankei ran an article by Yoshihisa Komo-ri accusing Clark of dismissing the North Korean abduction issue as a fiction. Clark says this was entirely inaccurate, but the damage was done.

Shortly afterward, in 1995, Clark was asked to be vice president of Tama University, stepping up to president a few months later when the incumbent suffered a heart attack. Later Clark served as vice president of Akita International University from 2004 to 2008.

Along the way, he has found time to write half a dozen more books, serve on numerous government committees, appear as a commentator on Japanese TV and write regularly for publications from the International Herald Tribune to the Japan Times – his eventful path being very different from the one he envisaged as a young diplomat.

“I’ve enjoyed the transition, but I never had the chance to properly use the Chinese and Russian that I learned. That's a big regret in my life, particularly the Chinese.”