Issue:

For over 70 years since it began printing in war-ravaged Japan, the Stars and Stripes has offered its military community readers a taste of press freedom, U.S. style.

It owes its initial creation to the celebrated Gen. “Black Jack” Pershing, who commanded U.S. troops in WWI. During WWII, U.S. Generals Patton and Eisenhower once engaged in a rancorous disagreement over the rumpled and unshaved appearance of cartoonist Bill Mauldin’s GI characters Willie and Joe that appeared on its pages. (Mauldin would receive a Pulitzer Prize for his efforts.) And among the more celebrated readers of the U.S. military newspaper the Pacific Stars and Stripes edition was Hirohito, then emperor of Japan (see sidebar).

While U.S. soldiers began receiving the Stars and Stripes in the European theater as early as 1942, it did not appear in the Pacific until three years later. Issues printed in Hawaii first appeared in Japanese territory in May 1945, distributed to the troops and ships at sea while the battle for Okinawa was still in progress.

The Tokyo edition was launched in October 1945, consisting of four pages, distributed free of charge. Printing at first was outsourced to the Nippon Times (as the Japan Times called itself from 1943 to 1956), but before long the Stripes had its own building and was being typeset and printed in Roppongi, on a site that originally quartered the Third Imperial Guard of the Imperial Japanese Army.

In the years after the occupation ended the Stripes enjoyed its golden age as a city newspaper with extensive local coverage. Its Tokyo bureau generated considerable local content, running columns by such popular regulars as entertainment columnist Al Ricketts and sportswriter Lee Kavetski. The late special correspondent Hal Drake, long a fixture at the FCCJ Main Bar, proved a virtuoso at compiling oral histories, tracking down and interviewing Japanese who willingly gave personal testimonies about their involvement in the Pacific War.

Another celebrated Stripes alumnus was Texas native Millard “Corky” Alexander, who in February 1970 launched another tabloid, the free community newspaper Tokyo Weekender. “We had a bar, and the manager, a master sergeant, lived right next door,” Alexander once recalled to a UPI reporter, about what the Stripes had been like in its heyday. “He’d open the bar at 8:45 in the morning, but he’d consent to open earlier if it was an emergency.”

In 1985 the Stripes’ Tokyo newsroom still maintained an editorial staff of 82 – 44 military personnel and 38 civilians. That figure was to shrink drastically in the ensuing years, as the Washington headquarters assumed control over editorial work. “We used to have several versions of the paper, up to six at one point,” said current commander, Air Force Lt. Colonel Brian Choate. “We now have just one. We used to have a lot of folks scattered all over the Pacific. Today we have 16 offices located around the Pacific.”

A typical edition, selling for 50 cents (“Free in deployed areas”) consists of about 32 pages, of which nine are devoted to sports coverage. Most of the military-related stories are generated by in-house writers, with other news and op-eds from the Washington Post, Los Angeles Times and syndicated wire services like AP.

Delivered to homes in some areas as well as sold from vending machines, Stripes print editions are issued Monday through Thursday and special Weekend Editions on Friday. In addition to the regular newspaper, readers in Japan, Okinawa, South Korea and Guam receive weekly or biweekly supplements carrying area-specific news and feature articles, along with local advertising.

The Stripes greatest recent growth, not surprisingly, has been in its electronic versions, and the paper is making an effort to move from newsprint to digital. “Visits to the stripes.com website range from 1.5 to 4 million sessions a month,” said Choate. “Quite a few folks from outside the region log on, looking for information on this region.”

Choate gives especially high praise to the 147 Japanese nationals employed by the paper, a highly skilled labor force involved in printing, design work, distribution and other tasks. Printing of the daily edition and work on the electronic edition, along with the advertising sales are conducted at Hardy Barracks in Roppongi, across the street from Aoyama Cemetery. The building’s ground floor features a small Navy exchange and surprisingly large fitness gym.

“We have our mission first, and we look to that mission before we look to the bottom dollar.”

The Roppongi facility also once housed the Stripes’ Japan bureau and distribution departments as well, but some years ago these shifted to a nondescript one-story building on Yokota Air Base. Some staff must rise before the dawn for the long commute from Yokota to Roppongi.

While largely dependent on non-appropriated funding, the Stars and Stripes is partly subsidized by American taxpayers. (In 2014 it was allocated $7.8 million.) “We do get some appropriation, but the majority of our funds have to be self generated,” Choate explained. “So we’re never going to turn a profit. We have our mission first, and we look to that mission before we look to the bottom dollar. However, we cannot operate without some sort of revenue, so we’ve had to develop a business side here in Tokyo proper, and we’ve done that.”

Their distribution outlets are limited. Civilian sales in Japan are out; Stripes cannot sell to non-military subscribers, although in many Southeast Asian locales, copies of the paper can be found for sale at hotel bookstands. According to Japan/Guam area manager Monte Dauphin, copies go out on a daily flight to Singapore and are shipped as far as to the U.S. Naval Support Facility at Diego Garcia in the southern Indian Ocean. “Which probably makes us the longest paper route in the world,” says Dauphin.

It’s understandable that media watchers might harbor expectations that the newspaper is no more than a propaganda organ for the purpose of indoctrinating American troops. But Choate is quick with his denial: “The thing that remains one of our most prominent features is the First Amendment protection,” Choate stressed. “There is no influence over our content whatsoever. We are completely editorially independent, so no commander can tell us to censor anything. It’s always been that way, and it’s enforced today more than ever.”

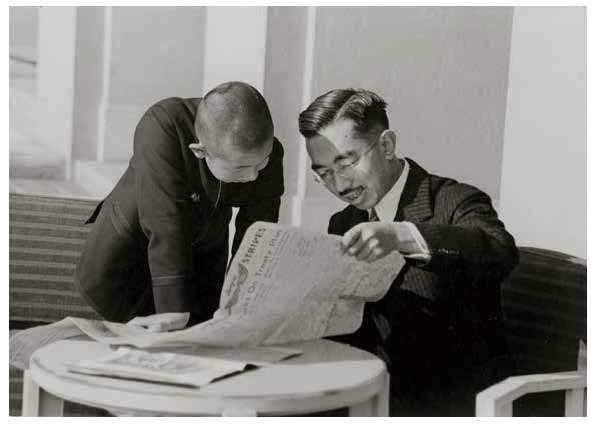

Emperor and emperor-to-be share a Dec. 27, 1945 edition of the paper.

So with U.S. politics virtually certain to become ensnarled in a bellicose presidential campaign in the months ahead, I asked Choate how the paper would negotiate the tightrope between the two parties’ candidates. His response and who can blame him? was to cringe in mock terror. “When we pass on our news and information, it’s the most up-to-date and accurate that we can manage, without any taint at all.”

Not leaving such matters to chance, in the early 1990s Congress created the post of ombudsman, to ensure that “journalists operate with editorial independence and that . . . readers receive a free flow of news and information without taint of censorship or propaganda.”

Choate emphasized that under the Department of Defense the Stripes is “the only entity with such privilege, and I think that makes us extremely unique.”

THE EMPEROR READS THE FUNNIES

AS 1945 DREW TO a close, officials of the Allied Occupation, including Gen. Douglas MacArthur himself, were busily engaged in preparations for a major PR makeover for Emperor Hirohito. This was to culminate in an imperial rescript, issued on New Year’s Day, that became known as the Ningen Sengen (“declaration of humanity”), in which the emperor denied his divinity.

In preparation for the announcement, Shogyoku Yamahata, a veteran photographer on contract with the then-Imperial Household Ministry, took a series of photographs of Hirohito and his family.

An extensive collection of the photos including some never before made public were recently displayed at a month-long exhibit in Tokyo. The photograph used on the flyer showed a seated emperor and standing crown prince reading the U.S. military newspaper, the Pacific Stars and Stripes, dated Thursday, Dec. 27, 1945.

Five pages of Yamahata’s photos originally appeared in the Feb. 4, 1946 issue of Life magazine, under the headline “Sunday at Hirohito’s Emperor poses for first informal pictures.” The caption suggested Hirohito and his heir apparent were interested in more mundane aspects of American culture like the Blondie and Moon Mullins cartoons at the bottom of page 2 than the front page story, “Big 3 Works on Treaty Plan.”

“The Japanese imperial household granted permission to Life as a ‘special honor’ to use four Sundays in December photographing the members of the imperial family,” the story read. "Since the family is fearful of assassination, American photographers were barred and Japanese photographers of the Sun News Agency used.”

At that point in time, the decision had yet to be made by the Allies concerning charging Hirohito with war crimes or demanding his abdication. As Life pointed out, “What happens in the future to Hirohito’s status will not be particularly influenced by the facts that he is a model family man, aged 44 . . . who was strongly opposed to the war.”

Still, the makeover of the Emperor’s public persona including this photo showing him reading newspapers published by his former enemy no doubt played a significant role in keeping him on the chrysanthemum throne.

Mark Schreiber’s ties to Stars and Stripes extend back to 1958, when he sold the European edition (at 5 cents each) to U.S. soldiers in Aschaffenburg, Germany.