Issue:

Ichiro Urushibara’s story reads like a gallop through the rise and fall of Imperial Japan right through its postwar economic miracle.

That Ichiro Urushibara’s journey through life would take a tumultuous route was perhaps first ordained when his father, Mokuchu, joined the delegation to the Great Japan Exhibition in London. The year was 1910, less than a half century after the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate and only five years after Japan marked its dramatic debut into the inner corridors of world power through its victory in the Russo Japanese War.

The elaborate exhibition offered the British public a chance to catch a glimpse of Japan’s arts and crafts, swords, temple gates, gardens and the woodblock art of Mokuchu Urushibara, who demonstrated his technique each day to rapturous audiences. And while the sight of 36 half naked sumo wrestlers may have raised Edwardian brows, it did nothing to inhibit the exhibition’s popularity, with one Sunday near the end of its run seeing an estimated 500,000 visitors. All told, between May and October, some eight million people swarmed to the site at Shepherd’s Bush. (In an intriguing small world aside, it was Count Hirokichi Mutsu, then a diplomat at the Court of Saint James, and father of FCCJ legend Ian Mutsu, who is widely acknowledged as the impresario behind the sensational success of the exhibition.)

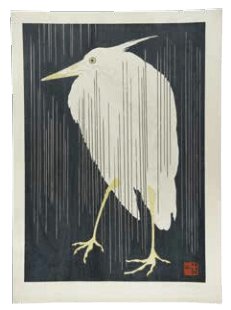

The welcome was enough to convince the woodblock artist Mokuchu to settle in London, where he went on to make quite a name for himself in the art world. Credited with introducing Japanese color print making techniques to Europe, many Mokuchu Urushibara works remain today in the collections of famous museums.

It was in London that he and his Japanese wife welcomed their son Ichiro into the world in 1930. The Great Depression wasn’t the easiest of times to be growing up but thanks to his father’s growing fame Ichiro could count luminaries like the artist Sir Frank Brangwyn, a frequent collaborator with his father, and art scholar Laurence Binyon among those close to the family from his earliest days.

But it was unlikely that he or anyone else suspected the twists and turns his life would take. The first clouds began to gather over the clan’s comfortable existence in England as the Nazis extended their reach across Europe. The Japanese exodus from England started in 1939, but the Urushibara family stayed on, even as they witnessed the German Blitz on the city of London. But the signing of the Berlin Pact between Japan, Italy and Germany was to seal their fate, and by the end of October, 1940, the family was boarding a Japanese ship in Galway Bay to “return” to a country the children had never seen.

As Ichiro Urushibara tells the story one recent afternoon over a cup of tea at the FCCJ, it is but one of many pages from his childhood memories. The uprooting from the Englishman’s life Ichiro had once assumed was his by right, however, must have been particularly jarring. The family could take little with them. But at least, he says, “the large, brightly illuminated Japanese painted flags on the ship guaranteed us free passage through an Atlantic swarming with trigger happy U-boats.”

Urushibara saw a lot of the world as the ship made its way to his ancestral homeland. After a brief stop in Bermuda, the ship travelled to New York, which Ichiro remembers as a dazzling city of lights “with no rationing!” and more ice cream than he and his sister could have ever imagined in wartime Britain.

Soon he was “home,” living in Setagaya and trying to assimilate. Urushibara makes little issue today of the prejudice toward the returning Japanese his family encountered. “We rarely mentioned we had dual nationalities, though, or that we spoke English,” he says. “That would have been asking for trouble.”

On Monday, Dec. 8, 1941, Urushibara remembers cheering along with classmates when it was announced on the radio that Pearl Harbor had been attacked, and that Japan was at war with the U.S. But as the war escalated and the population suffered from increasing shortages of almost everything, Mokuchu’s hybrid woodblock art, which had found such favor in Europe, became but memories of a vanished world.

In the last desperate days of Japan’s disastrous Pacific campaign, even Ichiro’s then 56 year old father was drafted. The elder Urushibara escaped the clutches of combat when a friend secured him a job in a factory, and Ichiro is convinced that even at 14, he would have been next had the war continued.

But the U.S. incendiary bombing campaign of March 1945, in which 100,000 people reportedly were killed in a single day, took care of what little Tokyo had left to fight for. “We were at our house in Setagaya when the first of the bombs fell on March 10,” says Urushibara, “and we could see the downtown skies turn bright red. But that wasn’t the end of it. On May 25, the raids came much closer, but when we started to evacuate, we saw that skies around us were ablaze in all directions. We thought, “First, the Blitz, then repatriation to the opposite end of the world. Now this. We said, ‘What the hell,’ and just stayed at home.”

And a good thing they did. While they were kept busy putting out fires while the bombs dropped all around them, their house miraculously survived, though nothing else beyond three doors down made it through the conflagration. In the process, Urushibara became a bit of a local hero, as his hand built battery operated radio was the only source of updates on raids through numerous power outages. “I was shouting, ‘The Americans are coming, the Americans are coming!’ around the neighborhood.”

And come they did, in the form of the Occupation, an initially much dreaded event that was to launch Ichiro’s life on a new trajectory. Unable to afford finishing high school, Urushibara’s bilingual skills even at 14 were good enough to immediately land him a job during his middle school summer holiday as an interpreter at the Ernie Pyle Theater, on the site of the Takarazuka Gekijo in Hibiya, which was a theater for the Occupation forces. The pay was okay, and the food “incredible.”

The new Japan rising from the ashes was short of English language expertise, and offers came pouring in from all corners. He did one stint in the Civil Censorship Detachment, poring over documents in order to enforce MacArthur’s “Thou Shalt Not Speak Ill of the Allied Powers” rule. He began working for commercial radio broadcasters under the name “Ken Tajima,” to separate it from his business and political endeavors, which included work for multinational firms such as Toyota, Time Life and Hill & Knowlton, as well as the private office of a secretary to a prime minister.

Somehow, he also managed to become the nation’s most trusted interpreter as well, lending his impressive talents to high profile conferences and events. His diverse careers saw him travel to 51 countries.

Still fresh in his memory is the series of broadcasts he did for TBS, simultaneously interpreting the conversations between the astronauts and control on the Apollo missions. He remains very proud of having been the only simultaneous interpreter doing the Apollo 11 to 17 moon landings who converted the astronauts’ measurements to metric in the live simultaneous interpreting.

But it was through his work at the U.S. Embassy that Ichiro met Yuko, a radio program producer in his department. Elegant, and a rare female university graduate in that era who spoke refined English, thanks to her English literature studies. Yuko’s father and grandfather were viscounts and prominent ministers under the Meiji and Taisho Emperors, and Yuko chuckles as Ichiro recounts the early days of their courtship under the guarded eye of the distinguished family. Though some what dubious about the prospect of their daughter marrying a repatriated “nobody” from a former enemy country, the family’s prewar lifestyle and affinity for western culture probably made it easier to reconcile their daughter marrying a “commoner.”

By the time the Olympics rolled around in 1964, “Ken Tajima” and Ichiro Urushibara were both bona fide stars. Ichiro even appeared stateside in a Schlitz beer commercial, with Yuko making a guest appearance in kimono.

An afternoon with the Urushibaras is a unique and deeply penetrating glance into the clash, demise and eventual synthesis of samurai, Empire and afternoon tea. Raised by parents determined to produce good British citizens, Ichiro knew little Japanese into his teens, while Yuko, through her aristocratic connections, went through Gakushuin, where she was sempai, by one and two years, respectively, to Yoko Ono and the Emperor.

“I still have the birthday book autographed by Yoko,” she says of those privileged prewar days. Also to be found in the pages is the signature, “Akihito,” from none other than the current emperor.

The Urushibaras’ memories from their multiple careers still astounds. Ichiro met Fidel Castro in Havana, and can recall an impressive list of the world’s greatest celebrities like Sammy Davis Jr., Connie Francis and Pat Boone who sought a spot on his popular radio shows. Yuko also had her fair share of exposure to celebrity through her father being a great fan and benefactor of baseball. His friendship with baseball legends Lefty O’Doul and Lou Gehrig, in particular, gave Yuko the chance to meet the biggest stars of the day players like Joe DiMaggio and Shigeo Nagashima.

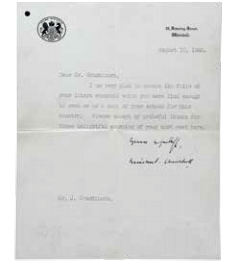

Ichiro wishes his father, who died in 1953, could have lived long enough to have enjoyed those heady days of his successes. He still holds dear a letter from none other than Winston Churchill, thanking Mokuchu for sending him a set of woodblock prints based on Brangwyn’s sketches. “The letter was dated Aug. 12, 1940, in the midst of the worst days of the war,” he says. “You would have thought Churchill was rather preoccupied. We were all moved. It still makes me so happy to remember that my father received a letter from 10 Downing Street in recognition of what he had achieved in England.”

The letter arrived just weeks before the Urushibaras left for Japan. Today, after 75 years, and celebrating 50 years at the FCCJ last year, Urushibara is still admitting to not feeling entirely Japanese nor British. “Neither fish nor fowl,” he says.

Others might call him a global citizen before his time.

Mary Corbett is a writer and documentary producer based in Tokyo. She is a board member of the FCCJ.