Issue:

September 2025 | Richard Hughes Part 1 of 3

The misadventures of Richard Hughes

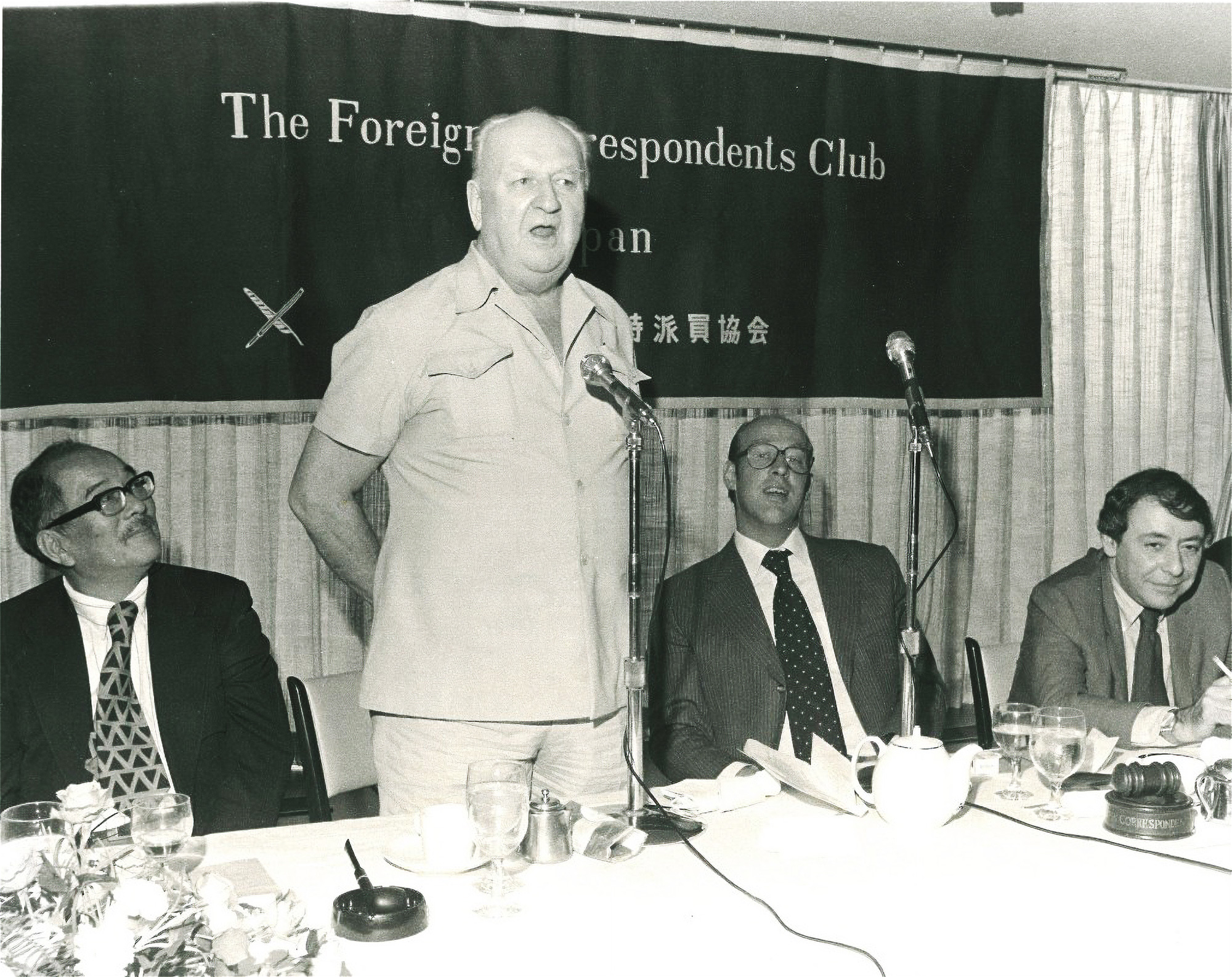

Richard ‘Dick’ Hughes, prolific Australian scribe and part-time spy for MI6, is usually associated with Hong Kong, his home for the final decades of an extraordinary life. Too often overlooked are Hughes’ thirteen years in Japan, including a riotous Occupation-era tenure as manager of the recently formed FCCJ. In his 1972 memoirs, Foreign Devil, the experience fills an entire chapter, aptly called ‘Down and Out in Shimbun Alley.’

Hughes had fallen out with his newspaper employer in Sydney after receiving an imperious recall summons: ‘I will deal with you when you return.’ Impetuously, Hughes cabled his resignation, and found himself in 1947 ‘unemployed, impoverished, emaciated, replete only with self-pity’ in Tokyo. By chance, correspondents were demanding reform of the Press Club, and in ‘a drunken and uproarious vote of endorsement from the membership’ Hughes was chosen as manager, at $80 a week plus free board and half-price drinks.

The Club combined ‘some of the features of a makeshift bordello, inefficient gaming-house and black-market centre,’ wrote Hughes. Above the ‘familiar uproar of intellectual disputation, breaking glass, knuckle play and folk singling in the packed bar’ would come the ‘occasional cackle of small-arms fire on the top floor, where some of the prickliest, gun-happy Pacific war veterans’ were holed up.

The ‘dilapidated, rat- and cockroach-infested premises’ had been requisitioned by General Douglas MacArthur for the accommodation of the world press. Landlord Mitsubishi baulked at paying for repair and renovation, so Hughes and Club president Tom Lambert of the AP petitioned MacArthur in person to intervene. The American Caesar agreed to despatch an Eighth Army colonel to join an inspection of the premises by three members of the Mitsubishi board, which later agreed to stump up ¥285,000 for immediate renovations.

The Club continued to teeter on the edge of insolvency. To save money, an executive committee headed by Keyes Beech of the Chicago Daily News decided in 1948 to fire Hughes. The decision reached him by cable while he was holidaying in Australia. Hughes replied, “We have a very short, sharp, ugly word for such practices.”

Luckily for him, there was to be no return to penury or humiliation. In place of ‘marginal freelancing’ for Australian news services and the likes of The Wall Street Journal and The Financial Times, Hughes was able to ‘stow aboard’ The Economist and The Sunday Times of London, where the welcoming foreign manager was Ian Fleming, creator of James Bond.

A study in contrasts

Fleming was the epitome of an upper-class Englishman. Grandson of a wealthy Scottish banker, he was born in London’s aristocratic Mayfair and attended Eton and Sandhurst. His father was a member of Parliament who after joining the British army, was killed on the Western Front in 1917. The cigarettes Ian Fleming chain-smoked through an ebony holder were custom-made in London from a special blend of Balkan and Turkish tobaccos.

Heavily built and forever ebullient, Hughes made Fleming look reserved, slight and frail.

Hughes’ father was a leading ventriloquist who imparted to his son a gift for oratory, humour and the stage. His mother on the other hand was a strict Catholic and Richard attended a Christian Brothers’ College. After a peripatetic start as a poster artist, train shunter and PR for Victoria Railways, Hughes entered journalism in 1934, starting at the short-lived Melbourne Star before joining Frank Packer’s Telegraph titles in Sydney, where he rose to become chief assignment editor for both the daily and Sunday editions.

Fleming worked briefly for Reuters in the 1930s, covering the Stalinist show trial in Moscow of six engineers from the British company Metropolitan-Vickers. Having sent a pro forma request to interview Josef Stalin, he was astonished to receive a handwritten note of regret.

After a spell in London banking and stockbroking, Fleming was recruited as the personal assistant of the Royal Navy’s director of intelligence. Throughout World War II, Fleming planned numerous intelligence operations, in collaboration with the Secret Intelligence Service (‘MI6’), the Special Operations Executive, and other clandestine agencies.

After the war, Fleming joined the Kemsley Group, owner of the Times and Sunday Times, as foreign manager, setting up a global network of correspondents nicknamed Mercury after its cable address. Many his recruits shared his background in wartime intelligence. More controversially Mercury provided ‘cover’ for several active MI6 agents. (In March of this year, the Sunday Times published the results of an investigation into the 1977 murder of its chief foreign correspondent, David Holden. The article quotes one of Fleming’s intelligence hires as saying that “half the foreign desk” were spies.)

Unlike his dashing James Bond alter ego, Fleming mostly worked behind a desk. In a 1964 magazine interview with Allen Dulles, first civilian director of the Central Intelligence Agency, Fleming let slip that he was afraid of flying. While greatly admiring John Le Carré’s book The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, Fleming said he wouldn’t want to take it on a flight “because it wouldn’t take my mind off the airplane. It might even increase my fear and nervousness.”

First trip to Japan

In 1940, Hughes borrowed £400 from his Sydney newspaper and took the Japanese steam-packet Osaka Maru to Japan. There was a mood of apprehension about a looming war in the East. During the three-week voyage from Sydney, Hughes learnt from the radio of the July 29 death of Reuters Tokyo correspondent Jimmy Cox, who fell from a high window of the Kempeitai military police headquarters in Tokyo’s Kudan while being interrogated as a suspected British spy. When the Osaka Maru docked in Sydney one week later, Hughes discovered that he was the only Australian journalist in Japan, just 18 months before Pearl Harbour.

Japan ‘was a fascist police state in 1940,’ Hughes wrote in Foreign Devil, in which the ‘Son of Heaven was Japan’s divine Führer – or infallible Chairman. Emperor worship was implacably enforced.’ When trams passed the Nijubashi Gate of the Imperial Palace, ‘the conductor barked a stern order, and everyone arose and joined in jostling obeisance … On the rare occasions when the chrysanthemum-crested, maroon-coloured limousine passed, all traffic was halted and all pedestrians halted with their eyes cast to the ground.’ To avoid offending Japanese by using his name in conversation, foreigners often referred o Hirohito as ‘Charles Smith’ or ‘Big Charlie.’

(Japan’s consul-general in Sydney rebuked Hughes for his article about the emperor in early 1941, in which he described his physical appearance. “Would an Australian Christian like a Japanese journalist to describe the physical appearance of Jesus Christ if Jesus were reigning, incarnated, in Canberra?” the consul asked seriously. “The emperor is Japan’s Jesus.”)

Invited to address a luncheon of the Japan-Australia Friendship Society, Hughes arrived to find three long empty tables in a private room. The only other people were the president of the Society, Prince Tokugawa, and ‘half-a-dozen waiters scratching their armpits.’ In the week after the invitation was sent to Hughes, Japan had signed the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy, ‘and the tone of the Japanese press had dutifully swung against the British Commonwealth as well as the United States.’

As a token of recompense, a Malacca cane was later sent to Hughes room at the Imperial Hotel, together with a formal letter signed by Prince Tokugawa and every member of the society’s Japanese committee, in deep appreciation for his ‘most helpful, illuminating and encouraging address.’

Sensing the imminence of war, Hughes packed his notebooks and left Japan at the end of 1940. He believed that Japan would commence hostilities in February, not December of 1941 when it attacked Pearl Harbour.

His despatches from Japan to the Sydney Telegraph assessed the war-readiness and capabilities of Japan’s armed forces and warned Australia to be better prepared.

By coincidence, an American was also researching Japan’s navy buildup while working for the British-owned Japan Chronicle in Kobe and the American-owned Japan Advertiser in Tokyo.Alwyne (‘Al’) Pinder later joined the Office of Strategic Services and worked behind enemy lines in China.

‘There were suggestions Pinder was the CIA station chief in Tokyo before he joined the Press Club. After his death [in 1989], friends helping his wife sort through his belongings found three different IDs with altered names,’ according to the FCCJ’s official history, Foreign Correspondents in Japan.

‘Stalin’s Spy’ Richard Sorge

Among the foreign press in Tokyo in 1940 was Richard Sorge, for Hughes ‘the greatest spy of them all.’ Accredited correspondent of the Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, confidant and press secretary of the German ambassador, and to all appearances in Tokyo and Shanghai a fervent Nazi, Sorge passed on German and Japanese military secrets read by Josef Stalin in Moscow and would eventually hang for espionage in Sugamo prison.

Hughes met and drank with Sorge several times at Nazi hangouts in Tokyo in 1940 and left us with an indelible pen portrait.

‘Sorge fascinated and repelled me as the prototype of The Nazi, tough, ruthless, arrogant, unscrupulous, bigoted, a bastard … In a group, he was generally silent and coldly attentive, or else hectoring and in sardonic command of the conversation … He drank heavily but I never saw him drunk. He excelled at liar’s dice. He had a habit of crumbling empty matchboxes and chewing toothpicks … At no time did he allow liquor or women to affect his judgment or distract him from his cooly efficient and audacious operations. He was, after all, a pro – probably the great of them all. His reflex guard, it seems, was never lowered. In all his drinking and writing, jesting and wenching, questioning and finangling, over nine tense years in Japan and Shanghai, he never once let slip a hint that he knew a word of Russian.’

Dissatisfied with standard accounts of the Sorge spy ring, Hughes posed two fundamental questions. One was why the Russians allowed Sorge to be hanged when the Japanese were prepared to exchange him. The other was why the Gestapo secret police and suspicious Nazis in Tokyo did not unmask Sorge as a communist, when his record as a Communist Party member would have been ‘readily available in the Berlin archives.’

Sorge’s paternal grandfather had been close to Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. After serving the Kaiser bravely in World War I and being awarded the Iron Cross, Sorge joined the Spartacist Uprising of 1919, and while most of its leaders were executed, Sorge survived and joined the German Communist Party (KPD) in revolutionary Hamburg.

‘He worked as a schoolteacher and coal miner in the Ruhr and also as a party organiser and subverter,’ Hughes pointed out. The Allied military government of the occupied Ruhr even ordered him to leave or be arrested as a communist agitator. In 1924, Sorge was ‘hand-picked for Party training in Moscow’ and travelled opened openly to Russia. After working as a ‘Comintern evangelist’ in Scandinavia and Britain, he was transferred to the intelligence division of the Red Army General Staff.

Hughes emphasises that most of Sorge’s Party record ‘had been filed with Teutonic thoroughness by German security bureaucrats.’ In Tokyo, Sorge stood out for his notorious access to the embassy, and reputation as a ‘bohemian’ journalist. ‘He would have been amusingly obvious in a James Bond adventure.’ Yet SS Colonel Josef Meissinger, the Gestapo chief who visited Tokyo in 1940 with a brief to help Japanese intelligence counterparts in anti-communist surveillance, and, in particular, to scrutinise ‘the operations and loyalties of German officials and residents,’ failed to spot anything amiss with Sorge.

Following Sorge’s arrest by the Japanese in 1941, a file check on Sorge was belatedly ordered in Germany, and Heinrich Himmler miraculously produced a damning dossier of evidence.

Slicing through a tangle of absurdities with Occam’s razor, Hughes comes up with what he considers the only plausible explanation, that Sorge was a double agent, trusted by the Nazis to spy on their Axis partners in Japan, while also spying for Moscow.

Robert Whymant, a Tokyo correspondent for the Guardian, Sunday Times, Telegraph and The Times who died tragically in 2004, inherited Hughes’ fascination with Sorge. He spent 20 years tracking down survivors of his spy ring, as well as accessing newly opened Soviet archives for his book ‘Stalin’s Spy.’ Yet for all the fascinating detail, colour and narrative verve that Whymant brought to the case, he failed to dispel the doubts harboured by Hughes or disprove his conclusion.

Peter McGill is a U.K.-based writer. A former Tokyo correspondent of the Observer, he was the youngest-ever president of the FCCJ.