Issue:

September 2025 | Gaza Media Special Report Part I

Reporters in Gaza are being killed at an astonishing rate. Why haven’t their colleagues in the West done more to help?

Copernicus Sentinel data of the Gaza strip, 2023 - Wikipedia

In October 2023, Wael al-Dahdouh, still wearing his press flak jacket, found the bodies of his son Mahmoud, 15, his daughter Sham, 7, and his wife Amina lying in a makeshift morgue outside the Nuseirat refugee camp in Gaza. Amina and the children had been sheltering in a designated “safe zone” when they were hit by an Israeli missile. His infant grandson Adam was also subsequently declared dead.

A few months later, Dahdouh, Al Jazeera’s bureau chief in Gaza, was himself badly hurt in an Israeli missile strike that killed his cameraman, Samer Abu Daqqa. While Dahdouh recovered, his eldest son, Hamza, also a journalist, was killed by an Israeli drone. The list of fatalities in Dahdouh’s family in Gaza includes five nephews and their father, as well as several other relatives – “all innocent people”, he notes.

Now recovering in Doha, Dahdouh has become a symbol of what many are openly calling Israel’s war on not just Al Jazeera, which has lost 11 reporters to attacks by the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF), but what Amnesty International calls an assault on “journalism itself”. He is also a potent emblem of professionalism in the face of horrific suffering: a few hours after he buried his family, Dahdouh was back on camera telling the world about the war.

Nearly two years since Israel launched its assault on Gaza after Hamas murdered and abducted innocent civilians in Israel on 7 October 2023, the only journalists reporting on the ground are being systematically picked off by the IDF.

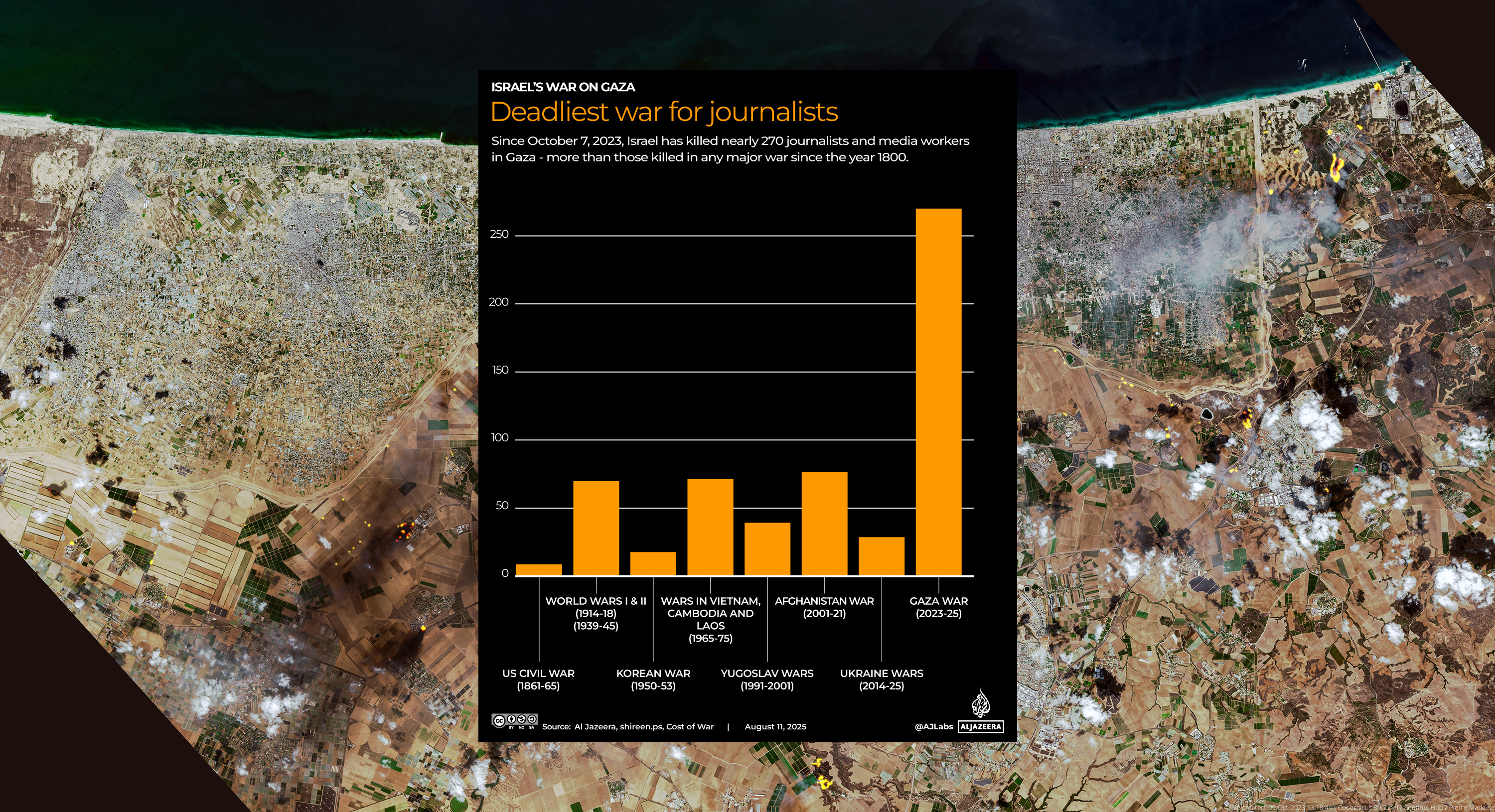

Just two months after Israel launched its attacks on Gaza, the UN said it was alarmed by the “unprecedented” killing of journalists and media workers there. At the time, UN authorities had confirmed the deaths of 50 journalists; today, estimates put the figure four or five times higher.

More journalists have lost their lives in Gaza than in the U.S. Civil War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War and several other modern conflicts combined, according to a study by Brown University, which condemned what it called Israel’s “unrelenting war on the press”.

The media death toll in the region began rising long before October 2023. In the preceeding two decades, Israeli forces killed 26 journalists, among them Shireen Abu Akleh, who won the FCCJ’s Freedom of the Press Asia Award in 2023.

In August, The Committee to Protect Journalists [CPJ] said the period since 7 October 2023 had been the most deadly for journalists since the US-based nonprofit began gathering data in 1992. It cites 186 journalists and media workers killed in Gaza, the West Bank, Israel and Lebanon since the war began.

Killing journalists with impunity

The IDF continues to “target journalists with impunity”, according to the media watchdog Reporters Without Borders (RSF) in its latest report. This followed the targeted killing of Al Jazeera journalist Anas al-Sharif and four other media workers in an Israeli airstrike on August 10 this year. RSF has filed four complaints with the International Criminal Court for Israeli war crimes against journalists and demanded an emergency meeting of the UN Security Council, based on Resolution 2222 of 2015 on the protection of journalists in war.

The UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression, Irene Khan, said in July she was “deeply alarmed by the repeated threats and accusations of the Israeli army” against al-Sharif who, like Dahdouh, was a particularly high-profile reporter in Gaza. Khan cited “growing evidence” that journalists in the territory have been targeted and killed by the Israeli army “on the basis of unsubstantiated claims that they were Hamas terrorists.”

The same month, Agence France-Presse released a statement warning that its reporters in Gaza were facing death from starvation and exhaustion, “the first time in the agency’s 80-year history that a humanitarian alert has been issued on behalf of its own journalists”. The Society of Journalists at AFP said that while they “have lost journalists in conflicts” since 1944…“none of us can ever remember seeing colleagues die of hunger”.

Dahdouh says this was always the Israeli government’s intention. “This is clearly linked to Israel’s objective of concealing the truth from the world, isolating Gaza, and ensuring that the war crimes and crimes against humanity it commits – including those against journalists, doctors, and other civilians - do not reach the global public,” he told the Number 1 Shimbun from Doha. “Journalists have been targeted on this broad scale, and foreign journalists have been prevented from entering Gaza so that there will be no additional witnesses to the crimes being committed against Gaza and its residents by Israeli occupation forces.”

Western media failure

The ban on foreign reporters entering Gaza has caused frustration in newsrooms that, for the most part, are overly reliant on the Israeli government and Hamas for information. The only exceptions have been a handful of brief and tightly controlled visits to Gaza accompanied by the Israeli military, which prohibited reporters from speaking to Palestinians.

Official sources aside, major media organizations, from London and Paris to New York and Tokyo, have turned to Palestinian freelance reporters, photographers, and camera operators, who risk their lives to bring the story to worldwide audiences. For their bravery, many end up dead, injured or starving.

Dahdouh says the “resounding failure” of the Western media to accurately cover Gaza has only added to the territory’s misery. “Even now, many outlets have yet to adapt their editorial policies or approaches to reflect the exceptional reality and scale of what is happening,” he said. “Many, for instance, continue to broadcast the Israeli narrative in full from the outset, without bothering to verify its claims or consider the Palestinian account, which is represented by evidence, images, numbers, and facts on the ground that must be reported and highlighted.”

The “Israeli narrative” means, for example, the BBC reporting in August that Israel had approved a “controversial” West Bank settlement project, when the more appropriate word is “illegal”. Assal Rad, a historian of the modern Middle East at the Arab Center in Washington DC, chides what she calls Western media cover for Israeli actions: for “ethnic cleansing” read “relocation plan”; for “starvation” read “hunger crisis”; for “genocide” read “military operation”. “This is complicity, not journalism,” she says.

The gap between Western and Arab perceptions appears to be growing. In May, the Palestinian poet and Pulitzer Prize-winner Mosab Abu Toha posted on X a photograph of yet another dead Gaza child along with a furious denunciation of the New York Times and the rest of the Western media pack for “justifying his killing with your coverage”. After the killing of Anas al-Sharif, Palestinian writer and journalist Hamza Yusuf angrily denounced the Western media for complicity in his death: “The BBC, Sky News, LBC, Guardian, Times, Telegraph, Independent, Financial Times, New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, CNN etc. – every single Western mainstream media outlet has the blood of Anas al-Sharif on their hands,” Yusuf said on X. “Every single one.”

Al-Sharif had been killed in a tent for journalists outside al-Shifa hospital in Gaza City along with six other people, including another Al Jazeera correspondent, Mohammed Qreiqeh and the camera operators Ibrahim Zaher, Mohammed Noufal and Moamen Aliwa, according to the Qatar-based broadcaster.

Israel issues a rare apology in late August, when an IDF attack on Nasser hospital – the last functioning public hospital in southern Gaza - killed 20 people, including five journalists: Hussam al-Masri from Reuters, Mariam Abu Dagga (Associated Press), Mohammed Salam (Al Jazeera), Moaz Abu Taha (NBC) and Ahmed Abu Aziz, who worked for several local Palestinian media outlets as well as the Tunisian radio station Diwan FM.

According to witnesses, the IDF struck the hospital twice in a “double-tap” assault, the second strike coming just as rescue crews and journalists arrived to evacuate the wounded 15 minutes after the first bombing. The IDF attempted to justify the attack by saying they had been targeting a camera "positioned by Hama". The Israeli soldiers who had been ordered to carry out the strike later voiced anger that their government had apologized.

The International Association of Press Clubs, of which the FCCJ is a member, said in a statement: “Under international law, journalists are civilians and must be protected at all times. Attacks on medical facilities—particularly those resulting in the deaths of journalists and emergency personnel—must be unequivocally condemned and subjected to thorough, independent investigation. These acts not only endanger lives but also strike at the core of press freedom and the public’s right to information.”

In one of the most dramatic interventions by a journalist on the ground, the photographer Valerie Zink, who had worked as a stringer for Reuters for eight years, announced on X: "I can’t in good conscience continue to work for Reuters given their betrayal of journalists in Gaza and culpability in the assassination of 245 our colleagues."

Accusing the news agency and other Western media of effectively abandoning Al Sharif and other Palestinian journalists to their fate, Zink said she could "not conceive of wearing this press pass with anything but deep shame a grief. I don't know what it means to begin to honour the courage and sacrifice of journalists in Gaza - the bravest and best to ever live - but going forward I will direct whatever contributions I have to offer with that front of mind".

Reuters has stopped sharing the locations of its teams in Gaza with the IDF, citing the deaths of so many journalists, including that of one of its cameramen in the Nasser hospital attack.

Even well-meaning liberal voices seem to miss the point. The veteran BBC correspondent John Simpson infuriated Dahdouh and his colleagues when he posted: “The world needs honest, unbiased, eyewitness reporting in Gaza," which he said has “so far been impossible”. As Mohamad Bazzi, journalism professor at New York University noted, Simpson’s comment “reinforces the worst colonial traditions of legacy media, which view western (often meaning white) journalists as the sole arbiters of truth.”

The ban on foreign media in Gaza has created a vacuum that has been filled by Israel's powerful propaganda machine. A special Israeli military unit had been set up to identify reporters it can smear as undercover Hamas fighters, according to local media. The unit has one objective, according to +972 Magazine and Hebrew-language Local Call – to gather information that could bolster Israel’s image and keep allies (notably the U.S) onside despite the extraordinarily high casualty rate among journalists. This is the tactic Israel’s government employed after the death of Al-Sharif, whom it claimed had been a Hamas commander.

Journalists in the region have accused their colleagues in the West of failing to stand up for press freedom during a war in which journalists appear to be regarded not as collateral damage but as legitimate targets.

“Israel is able to kill Palestinian journalists with impunity not just because of the unconditional military and political support it receives from the US and other western powers, but also the failure of many western media organizations and journalists to stand up for their Palestinian colleagues,” Mohamad Bazzi, director of the Hagop Kevorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies, and a journalism professor at New York University, wrote in the Guardian in August.

Bazzi, a former Middle East bureau chief at Newsday, added: “Western outlets are often willing to publicly criticize governments and campaign for journalists who are harassed or imprisoned by US adversaries like Russia, China or Iran. But these institutions are largely silent when it comes to Israel, a US ally.”

Writing in the same newspaper, Jodie Ginsberg, the CEO of the Committee to Protect Journalists, said the deliberate targeting of media workers in Gaza – who are considered civilians – amounted to a war crime. “Israel always boasted that it was the only country in the region to support press freedom. That boast rang hollow even before the current war. Now, it’s not even pretending,” Ginsberg wrote days after Al-Sharif and his colleagues were killed.

Last month, journalists in London and other cities held low-key vigils for their dead colleagues, while pressure mounted on the Israeli authorities to allow reporters into Gaza to weigh up the claims and counterclaims about the condition of its 2 million inhabitants for themselves, including evidence in an UN-backed report (denied by Israel) that people in and around Gaza City are now suffering from an “entirely manmade famine”.

In recent weeks, 27 countries, including Britain, Germany and war-torn Ukraine, have demanded that Israel immediately give international journalists access to Gaza, to allow them to cover the “unfolding humanitarian catastrophe” there.

Without US pressure, Israel seems unlikely to grant this access. Instead, as the tragedy grinds on, we are far more likely to witness continued attempts by much of the western media to “Gaza” news coverage. That is a new verb that Phoebe Greenwood (citing a colleague in British television), the Guardian’s former Israel correspondent, recently used to describe the downgrading of a story’s editorial importance.

Greenwood, who reported from Israel and Palestine for almost four years, added: “Finally, it seems the forbidden words are being named – genocide, famine, statehood – and our leaders may act to do something about them. But our outrage has come much too late. Why did we wait? Our wary silence abetted the tragedy in Gaza. Our cynicism allowed for the defining horror of a generation.”

David McNeill is professor of communications and English at University of the Sacred Heart in Tokyo, and co-chair of the FCCJ’s Professional Activities Committee. He was previously a correspondent for the Independent, the Economist and the Chronicle of Higher Education.

Justin McCurry is Japan and Korea correspondent for the Guardian. He is the author of War On Wheels: Inside Keirin and Japan’s Cycling Subculture (Pursuit Books, June 2021), published in Japanese as Keirin: Sharin no Ue no Samurai Wārudo (Hayakawa, July 2023).