Issue:

September 2025 | Ripping Yarns

When the ex-Nissan CEO was arrested in Japan, I flew to Lebanon in search of his past … and his possible fate

The best stories find you before you find them. When Les Echos Japan correspondent Yann Rousseau and I learned that Renault-Nissan’s uber (no pun intended) CEO Carlos Ghosn had been arrested, we happened to be exactly in the right place at the right time. That place was Tokyo, where two governments and two car manufacturers (Renault and Nissan) were suddenly at each other’s throats over a man that had brought all those parties together for neatly 20 years.

Our proximity to the crossfire not only obliged us to write articles, but it also led to a book that we co-authored.

Carlos Ghosn is a man of “identities”, a word he relishes and incarnates: a French-Brazilian-Lebanese globe-trotting chief executive who became a global star while in Japan. But not all identities are created equal. Of all the pieces that form the Ghosn puzzle, the central one is Lebanon, where he spent his youth, where he was always most at ease and where this once global citizen may spend the last chapter of his life.

So after Carlos Ghosn was arrested, I twice flew to Beirut to understand him better. My first visit, made alone, was before his dramatic escape in a music box aboard a private jet. The second trip, with Yann, came after his audacious escape. Finally, of all the nicknames that he had accumulated like pins on a lapel – “cost killer”, “cost cutter”, “Mister 7-11 - he ended up with a much less complimentary moniker: fugitive.

I almost met Ghosn on two occasions after his arrest, but our appointments were cancelled at the last minute and then he refused to meet me. But that was only a minor setback, given how accessible and talkative people in Beirut are. Lebanon’s journalism problem is best described as a catastrophe of abundance that promises myriad fascinating sources, most of them located a WhatsApp click away in the rarefied downtown neighborhood of Achrafieh. An hour with any one of these spies, businessmen, bankers, art gallery owners, military officers or simple acquaintances of Ghosn, often in settings worthy of a James Bond movie, was the stuff feature stories are made of.

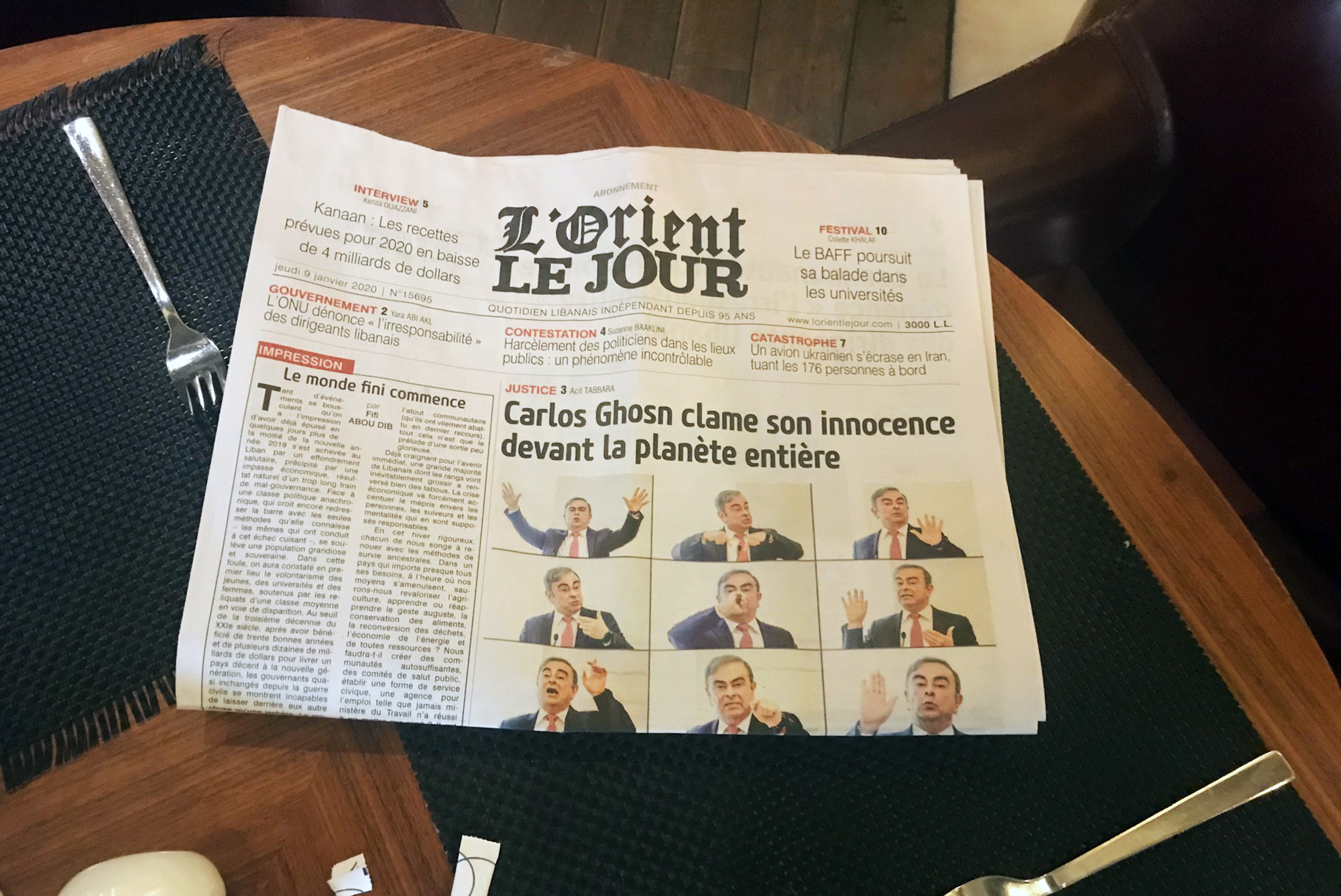

One object sums up my whole time there: a small case in beautiful, shiny leather that was on the backseat of a huge car that an ex-bridge partner of Ghosn had sent for me. The case featured a prominent Gucci logo, and its unusual L-shaped design led me to question its intended porpose. As a wallet? A glass case? It was a gun holster, the driver said with the broadest smile I have ever seen. The only truly unpleasant experience was an attempted extortion, or kidnapping, by three men who tried to drag me into their car at the exit of Lebanon’s great French daily newspaper L’Orient Le Jour. I escaped to a nearby gas station, and they gave up. I don’t believe, however, that the incident was related to the Ghosn story.

A question bubbled in my mind: where would the journey of a man of so many origins and associated with so many countries come to an end? Where would “Mr Globalization” put down roots? The family’s modern founder, Bichara Ghosn, had emigrated in early 20th century from a city called Jounieh, 20 kilometers north by car from Beirut. So one afternoon I booked an Uber to take me there. I assumed I would find a small village, but Jounieh is now a fairly big city. Disoriented, I stopped in what seemed to be its busiest district and wandered around alone, without much of a clue.

Several hours later I ended up in Couvent Saint Sauveur Sarba, a church with a stunning view over the Mediterranean Sea. However beautiful the place was, it was a dead end. My phone battery had run out, putting me out of reach of Uber, and I was starting to wonder how I would go back to my hotel. I saw a Western Union shop where, I assumed, people would speak English and help. “Sure I will call a cab for you. Have a seat, please”, said an affable man behind the counter before he started conversing in Arabic with my future driver.

As I waited, my eyes started wandering around the shop. There were stamps, piles of receipts, banknotes, an aircon in need of repair. I spotted a pile of business cards that appeared to be the shop owner’s. I zoomed on the name at the top of each card: “Bichara”. I remembered that Carlos Ghosn’s full name was Carlos Ghosn Bichara. Could it be that the two were related, even if Bichara is a first name? “Sure, we are related”, the shop owner said. A member of his family had married a member of the Ghosn family, he explained. “I can show you where the Ghosn family tomb is, if you want.”

He walked me to a small but beautiful stone house. It was isolated and a bit neglected, and appeared to be situated on private land. “This is it”, he said. Perhaps it was the tomb of his parents or of more distant relatives. Perhaps it contained the remains of Ghosns of an altogether different universe. Perhaps my – or his - English was too poor – or maybe he was stringing me along. The monument read, in Arabic: “The grave of the families of late Nadjib and Joseph Abdou Ghosn”, above which was the biblical quote: “Whoever believes in me, even if he dies, will live.”

Régis Arnaud is the Japan correspondent for Le Figaro, Challenges & editor of France Japon Eco. His latest book is Le tour du Japon en (presque) 80 histoires (Editions du Rocher).