Issue:

Proud of its historical impact, the drink is making headway in trendy bars everywhere

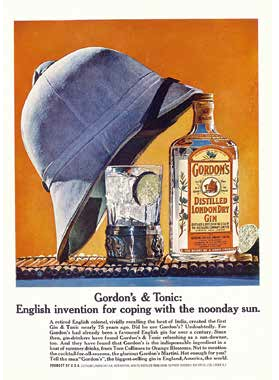

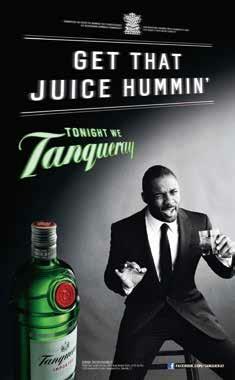

Stiff upper lip to soulful sips: An ad in a 1963 issue of Playboy celebrates the drink's colonial origins; a half-century later, distillers shun the past for a more youthful, trendy approach.

Capping two centuries of popularity, the Gin & Tonic is currently enjoying a phenomenal moment as the “it” drink at the hottest bars in New York, London and Tokyo. While the Main Bar at our own FCCJ upholds the classic taste, a new wave of dedicated artisans are on a quest for their intimately personalized Holy Grail, with passionate discussions about the best gin or the proper tonic ratio being held in bars all over the world.

The new gin boom is all about delivering the fullest flavor in every sip, and it’s riding on an explosion of new gin distilleries, many of them small boutique producers that have fans waiting months for their limited output. Apart from the essential juniper that all gins contain, the current wave of recipes have wildly differing levels of alcohol bursting with novel aromatic combinations like fruit peels, nuts and spices so lovingly nuanced that many fans now sip them neat. In just a few years, the new wave has already produced big name stars like the Botanist and Hendrick’s, which are quickly becoming the new standards, while the venerable Tanqueray still reigns as the perpetual favorite of traditional distillations. Even the ever-reliable Beefeater has recently added hints of Chinese tea and grapefruit to nine botanicals in a new super-premium edition.

Much of the new global obsession with gin can be traced to the aficionados of Spain, where the drink has grown from its first encounters through British Gibraltar to become a virtual national drink. Spanish artisans kept the devotion through the 1980s and ’90s, even as the drink was overshadowed everywhere else by vodka and other concoctions whose images were deemed more elegant than gin’s firewater image that it could never quite shed.

Barcelona is now the destination of the world’s most ardent fans, with a growing number of popular bars serving nothing else. Gone is the time-honored tall glass, which is now seen as an inferior vestibule for the unique aromatic blends of lovingly chosen botanicals and exotic garnishes. Now devotees seek out glasses with increasingly wider rims and plenty of swirling space some approaching the size of a kingyo bowl. And pre-chilled glasses with an optimal ice mass are now de rigueur to slow down dilution.

Gin’s ancestry can be traced back to the distilleries of 12th-century Salerno, Italy, but the version we enjoy today has its true roots in the popular Dutch drink gen a popular grain distillation from the coniferous juniper plant (genever in Dutch), long known for its medicinal properties. Records exist of a Dr. Sylvius de Bouve in Leiden, who had a best-selling juniper remedy for inflammation and kidney ailments in the 16th century.

THE SPIRIT

Popular legend tells of English soldiers taking a shine to a drink they called Dutch Courage while fighting on the Continent in either the Dutch War of Independence in the late 16th century or the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) and taking it back to England. From there gen evolved in stages into the London dry gin we know today.

Gin’s allure was further boosted when William and Mary ascended the English throne in 1688. Dutch and staunchly Protestant, William promptly slapped high duties on imports of wine and brandy from the detested Catholic countries and encouraged cheap gin production from grains grown in England.

Consumption predictably skyrocketed in the ensuing years, paving the way to perhaps the world’s first urban drug epidemic by the early 18th century. Society’s elites were alarmed by growing public drunkenness and crime, not to mention the dramatic drop in the numbers of able-bodied laborers, with magistrates declaring in 1721 that gin was “the principal cause of all the vice and debauchery committed among the inferior sort of people.” The government introduced heavy taxes in the 1730s, but the measures seem to have accomplished little but to send the sellers underground. The craze finally started to wane in 1751 when high license fees were imposed on gin shops through the Tippling Act, though spiraling grain prices may have had as much to do with the decline in demand.

THE MIXER

In a timeline echoing gin’s rise and fall in England, Spain was exploring the medicinal properties of a bitter bark that the Catholic missionaries in Peru had observed natives using to treat fevers, shivering and muscle cramps. Most significantly, it showed great potency as a cure for malaria, which presented a considerable obstacle for European expansionist ambitions into the tropical, mosquito-ridden regions of the world. (Malaria arguably has killed more people over history than all the wars and plagues combined.)

Soon, the Catholic Church was distributing the alkaloid powder ground from cinchona trees throughout the Old World at mind-boggling profit. But not everyone was enchanted with the drug. Quinine, as the active ingredient came to be known, was widely referred to as “Jesuit’s Powder” which led to Protestant rejection amid widespread suspicion of a possible Papist genocidal plot targeting them.

It was a bias that may well have killed Oliver Cromwell, who, dealing with his second attack of malaria in 1658, refused the doctor’s prescription of the powder and promptly took his last breath. A few years later, Charles II was also stricken with the disease. English, but a Catholic, he took his quinine and lived, as did his French, and very Catholic, friend Louis XIV.

To meet global demand, the cinchona seeds were eventually smuggled out of Peru, and large-scale plantations in Java were soon prospering under the Dutch.

THE ALCHEMY

The fortuitous wedding of gin and tonic took place in the 1820s. British troops stationed in India are believed to have come up with the ingenious way to make the gutwrenchingly bitter quinine more palatable. All manners of masking had been attempted, mostly by increasing the sugar content of the tonic. But low compliance for daily quinine ingestion remained a major concern in the colonies until some uncelebrated soldier (or soldiers) discovered what a magical bitterness-blocker gin could be.

The classic drink of the Empire was thus born, and Mary Poppins herself couldn’t have helped the medicine go down any easier.

The combination was to change history. With malaria outbreaks now largely under control, the British civilian population in India grew quickly, and the sparkling remedy became the most fashionable drink in the Empire.

THE CHILL

Helping its popularity in the planet’s hot spots was, no doubt, the addition of pristine ice. It came from halfway around the world thanks to the marketing ingenuity and acumen of flamboyant Bostonian businessman Frederic Tudor. Although his first shipments to Martinique and Cuba in 1806 turned out to be catastrophic meltdowns for both ice and investors, he tenaciously pursued technological innovations until he was able to harvest and transport his chunks of frozen ponds across the globe.

He cleverly targeted the tropical outposts, at first giving away samples to add to what were then rather tepid cocktails. With drug-like effect, the customers were soon hooked, making chilled drinks forever the norm and Ice King Tudor a very rich man. It was a case of Walden Pond meeting the Ganges. While Thoreau observed with bemusement workmen chopping away at ice blocks from his beloved Walden Pond, Tudor quickly conquered India. Buckingham Palace was soon to fall.

By the late 1820s, the notoriety of gin, once so painfully depicted in the “Gin Lane” prints of Hogarth’s 18th century London, was magically reinvented to help ease its entry into the grand salons of London’s high society, where it continues to hold a special place of honor to this day.

No less a man than Winston Churchill famously endorsed the drink for perpetuity when he proclaimed that “the gin and tonic has saved more English lives, and minds, than all the doctors of the Empire.”

THE GARNISH

The traditional crowning of the sparkling drink with a wedge of lime, or lemon as the preference may be, is also a tradition born of necessity during the relentless push for colonial expansion. On long ocean crossings in the Age of Discovery, scurvy would often kill up to 70 percent of the crew.

While Hippocrates knew some 2,500 years ago that a lack of fresh vegetables and fruits for extended periods would bring on the symptoms of scurvy, scientists later seemed more intent on finding culprit pathogens, and the debate raged for centuries while tens of thousands died at sea under the most horrific circumstances.

In 1747, Dr. James Lind published what may have been the first clinical study conducted in history, which made use of control groups to identify the efficacy of citrus fruits as scurvy preventives. His advice was pretty much ignored until 1794, ironically the year of Lind’s death, when on the insistence of officers, the British navy finally issued lemon juice for seamen (amounting to an extremely small 10mg per person ration) on the HMS Suffolk, which sailed for 23 weeks non-stop to India. Even on such a miniscule regimen, the citrus was enough to prevent serious episodes of scurvy, prompting the astonished Admiralty to finally issue citrus fruits routinely to the entire fleet, forever branding their seamen “Limeys” in the lingo of their mocking Continental neighbors. The Germans carried sauerkraut as their source of vitamin C on long journeys, hence giving the aforementioned Limeys a reason to call them “Krauts.”

Old gin lore has it that the preference for a wedge, rather than a drop of bottled or canned lime juice, was to prove its freshness, and thereby, high anti-scurvy efficacy. The lime wedge continues to protect us from scurvy. Alas, one would be ill advised to rely any longer on tonic as a malaria shield, as its quinine level is now legally capped at a fraction of the recommended medical potency. To compensate for the lapse of the defining bitterness of a bygone era, perhaps, devotees are now obsessive in their selection from amongst the ever-expanding choices of novel tonics on the market for which a well-matched garnish is now considered critical to gin and tonic’s unique alchemy.

Be your preference cucumber, a twist of yuzu, or something else unspeakably exotic you found at the market, what better season, or reason, to reexplore the full potential of the gin and tonic experience in the Main Bar on June 6, when Tanqueray will host an evening celebrating its legendary distillation, reintroduced to Club members with a 21st century touch: big ice, chilled glasses . . . and quixotic garnishes Queen Victoria couldn’t have even dreamed of.

THE TRADITIONAL CROWNING OF THE DRINK WITH LIME IS ALSO A TRADITION BORN OF THE RELENTLESS PUSH FOR COLONIAL EXPANSION

Mary Corbett is a writer and documentary producer based in Tokyo.