Issue:

March 2025

The media mark 100 years of Showa with nostalgia, and uncertainty over its legacy

In the early morning of December 25, 1926, 47-year-old Emperor Taisho succumbed to a heart attack compounded by pneumonia, thus bringing to an end the Taisho (Great Rectitude) era in its 15th year. Prince regent Hirohito immediately ascended the chrysanthemum throne, making the final week of 1926 Showa gannen, the first year of Showa (Enlightened Peace).

Who was to know at the time that Hirohito would eventually become the longest reigning emperor in Japan's history? When he died aged 87 on January 7, 1989, the final year of his reign, Showa 64, was also just one week in duration.

The timing of these events is also why this year in Japan – officially year seven of the Reiwa era – is also being treated in the print media as the 100th year of Showa.

But wait: Isn't this, some cynics might allege, just an artifice concocted by publishers to pique the public's curiosity, no more than a rehash of a similar wave of nostalgia that appeared after Emperor Showa died in 1989? And which was revived once again in 2019, when the Heisei era gave way to the current Reiwa?

Well, nostalgia sells. Particularly in a nation of history lovers. And publishers can't go wrong targeting the right demographic. As of July 2022, the approximately 80 million people born during the Showa era accounted for 70.4% of Japan's population. In contrast, Heisei accounted for 27.5% (30 million people), and Reiwa only 1.6% (just over 2 million).

This substantial Showa demographic, which ranges from nonagenarians to those in their mid-30s, are apparently still eager to read, and reminisce, about the era into which they were born.

As this writer noted in a previous article Trouble, rubble, toil and bubble published in 2017 (https://www.fccj.or.jp/sites/default/files/2021-03/05_May_2017.pdf), the three decades of the Heisei era, which spanned 7 January 1989 to 30 April 2019, were, to a significant degree, a period when Japan's politics, economics and popular culture continued to be buoyed by the momentum from the Showa decades that preceded them.

Among the publications planning centennial coverage throughout 2025 is the Sankei Shimbun. Its Tokyo bureau editor, Hiroshi Funatsu, remarked in Tsukuru magazine (March), "This year will see two major landmarks, the 80th year since the end of the war and the 100th year of Showa. From last year we've been running a two-page spread once weekly titled 'Showa year 100: Myself in those times.' Many members of the current working generation were born in the Showa years. It was truly a time of high-level economic growth and in the 50 and 60 years since then, Japanese society underwent major changes … Showa had good points but, of course, bad ones as well. We'd like to take this opportunity to look back on this 100th anniversary and look ahead to the next 100 years."

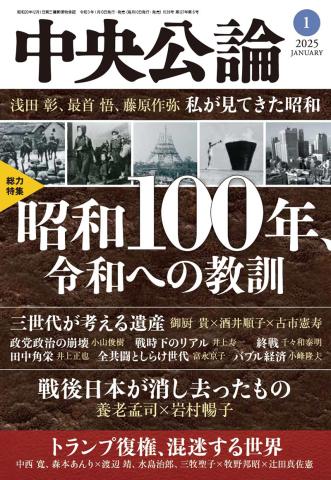

In its January 2025 issue, Chuo Koron magazine featured a special section titled Showa Hyakunen, Reiwa e no Kyokun (The 100th year of Showa, lessons for Reiwa). Much of its contents relate in some manner to events of the Pacific War – such as the military takeover of Manchuria that led to Japan's withdrawal from the League of Nations in February 1933. The issue also features a lively dialog between Takeshi Yoro, a medical doctor who has authored dozens of books, and writer Nobuko Iwamura titled "The things erased by Japan's postwar society."

Yoro basically downplays the Meiji Restoration and Japan's postwar American interlude, giving instead an entirely different reason for societal changes.

"I've been thinking," he said, "that the only things that have changed Japanese society were natural disasters. Japan's history is one of change through natural disasters … That’s the reason the Heian era changed to the era of the Kamakura Bakufu, in which the samurai took control. Kyoto had become overpopulated, requiring the transport of foodstuffs. However, in an era with so many natural disasters, rice on route to the capital would inevitably be stolen by bandits.”

He continued: “The Meiji Restoration was also said to have come about due to the arrival of [Commodore Perry’s] Black Ships, but the Ansei Earthquake that occurred one year afterward [in November 1855] also had a major impact. The end of the Taisho Democracy and the Showa era that culminated in war were impacted by the Great Kanto Earthquake [of 1923], in which the capital was destroyed and the promulgation of the Peace Preservation Law led to the collapse of the civilian cabinet.”

Yoro pointed out that more disasters are yet to come.

“When the anticipated Nankai earthquake hits,” he said, “I wonder what will happen. The distribution of goods will probably halt in the capital region and serious food shortages will occur. The key question will be how to restore the everyday life that has been disrupted. As I want to see how these changes play out, I hope to live until 2038 [the year when the quake is forecast], at which time I’ll have lived to the age of 101.”

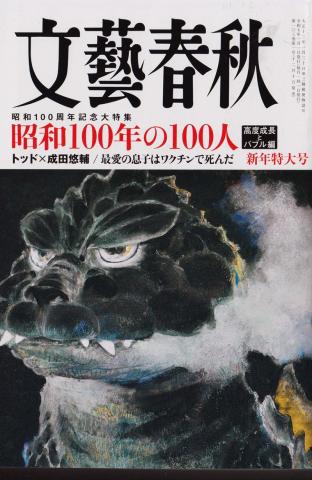

For the cover illustration in its January 2025 edition, Bungei Shunju magazine featured another Showa stalwart, Godzilla, as portrayed by artist Yuji Murakami. Inside, the issue introduces 100 people of the 100 years of Showa, with the listed individuals seen as representing the era of high economic growth and the bubble economy.

The section's editorial lead-in reads: We entered our adolescence while still carrying the sadness of Japan's defeat, and the Showa era came to its end amidst the glory of "Japan as Number One" and the frenzy of the bubble economy. What did we gain, and what did we lose? We look back through the memories of 100 people who stood out during our youth.

Sticking to the logical figure of 100, Bungei Shunju has also released three "mooks" sharing the title Showa Hyakunen no Hyakunin(One Hundred People of the Showa Century), compiled respectively into political, military and religious leaders; cultural icons; and the stars of sports and entertainment.

Starting with its February 9, issue, Sunday Mainichi magazine – which will mark its 103rd anniversary this April – began a series titled The 100 years of Showa as viewed by Sunday Mainichi. The first installment, based on the contents of its issue of January 2, 1927, included the ascendence of Emperor Showa and a critique of the so-called modan gaaru or moga (modern girl) phenomenon, as liberated females were referred to during the Roaring Twenties.

The demise of Emperor Taisho was anticipated, but the timing of his death was problematic and the Sunday Mainichi editors didn't have time to make last-minute changes. The magazine did produce a special New Year's entertainment edition at the end of the year, but no changes were made due to the unpredictability of the so-called X-Day [i.e., day of the emperor's death] and other scheduling concerns. Thus, Sunday Mainichi never produced an issue bearing a publication date in Showa year 1.

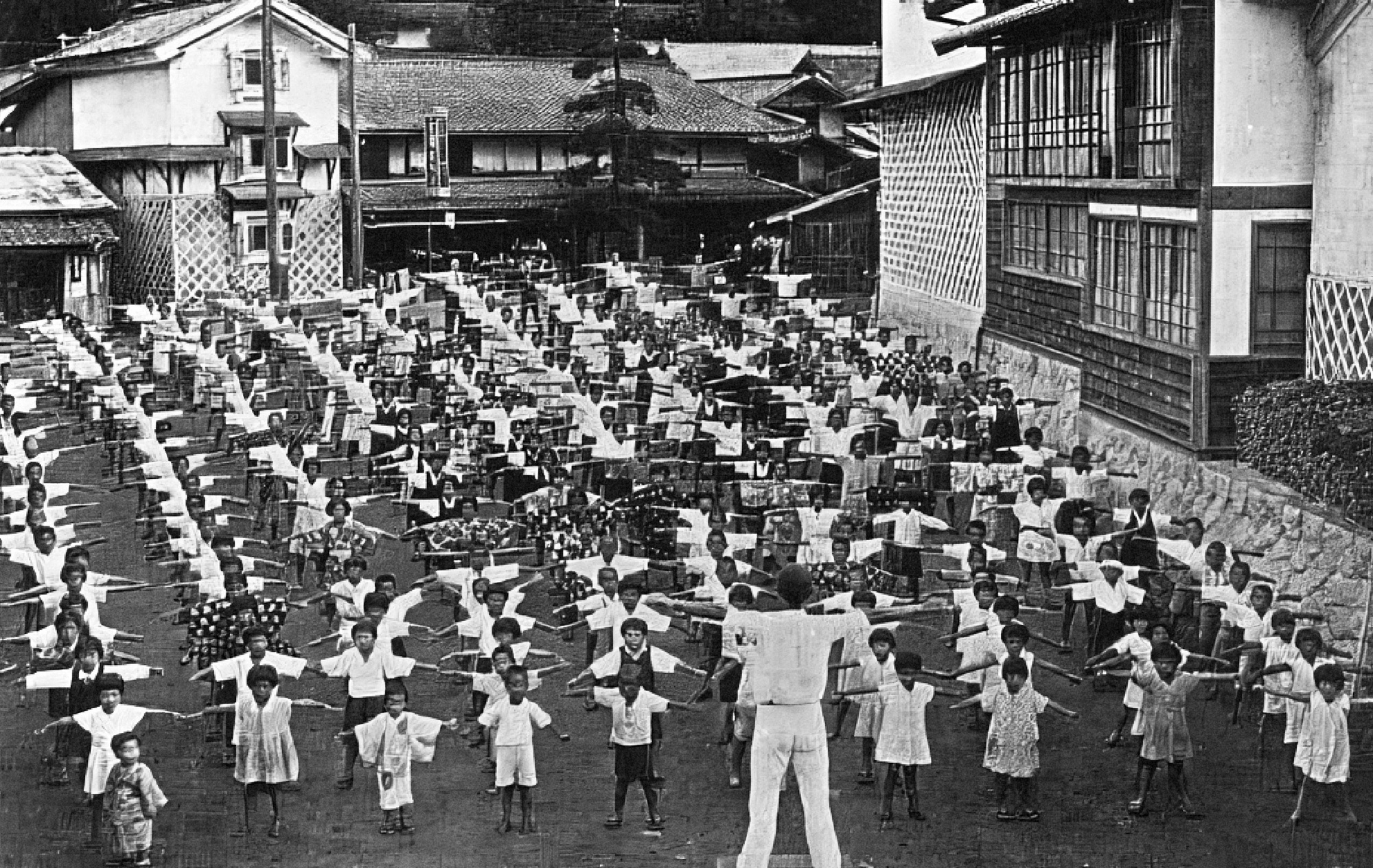

Sunday Mainichi also mentions the initiation of radio broadcasting by stations with the call letters JOAK in Tokyo from March 1925, JOBK in Osaka from June, and JOCK in Nagoya from July. These three were then reorganized to form the Nihon Hoso Kyokai (NHK) in 1926. By 1928, four new stations had been opened in Sapporo, Sendai, Kumamoto and Hiroshima, forming the beginnings of a nationwide radio network.

With characteristic elan, Shukan Taishu (January 27) covered a Showa century of sex, which included a nostalgic look back at television's “golden age”, when it was permissible to broadcast exposed female breasts on commercial TV. Bared female flesh was a regular fare on late-night programs, particularly on a popular show named 11 PM aired weeknights on Nihon TV and its affiliates.

Back in those days, even the samurai drama series Mito Komon included a peek-a-boo bathing scene featuring curvaceous actress Kaoru Yumi, and the late Miho Nakayama appeared undraped in a shower scene in another TV drama.

In its issue of February 10, Shukan Taishu featured a review of famous unsolved crimes and incidents of the Showa era. Part I covered such crimes as the ¥300 million robbery from Toshiba by a fake motorcycle policeman in December 1968 and the Glico-Morinaga Incident, a case of corporate blackmail in 1984-85, believed to have been a copycat crime inspired by the Tylenol murders (also unsolved) that had been carried out in the Chicago area two years earlier. Part II covered the enigmatic Teigin bank murder-robbery incident in January 1948, and several other cases that involved miscarriages of justice. Last year, Iwao Hakamata was finally absolved of any involvement in the Showa-era murders of a family of four in Shizuoka, 58 years after the crime and decades spent on death row. Part III featured a number of baffling cases, such as the unexplained death of Japan National Railways president Sadanori Shimoyama in 1949; the strangulation murder of a female BOAC flight attendant in 1959; the abduction of South Korean politician Kim Daejung from a Tokyo hotel in 1973; and the shotgun attack on the Asahi Shimbun's Hanshin Bureau in May 1987 that left one employee dead and another seriously wounded.

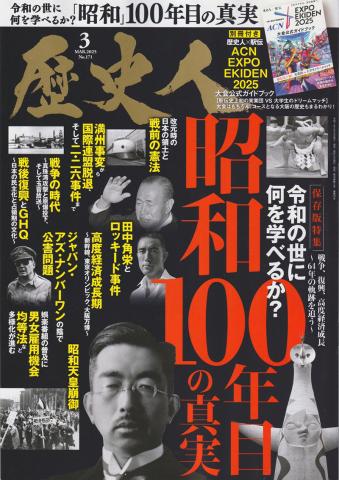

Rekishijin magazine, a monthly publication for history buffs, dedicated most of its March special keepsake edition to Showa 100-nen-me no Shinjitsu (The truths of the 100th year of Showa). Considering Showa's trajectory of war, recovery, and high-level economic growth, it asks rhetorically, "What can the Reiwa generation learn from this?"

Accompanied by dozens of photos and diagrams, the issue's main sections are, in order of appearance, the beginning of Showa (1926 to 1935); the war years (1936 to 1945); the way to democratization and recovery (1945 to 1964); the years of high-level economic growth (1950s through 1970s); maturing society, culture and living (1975-1989); and finally, a White Paper on the television that colored the Showa era, extending from the 1950s through the 1980s.

The name that seems to pop up most frequently when reminiscing about the Showa era is prime minister Kakuei Tanaka. A self-made millionaire nicknamed the "computerized bulldozer", who ascended to power with the expectation of shaking things up, Tanaka wound up resigning in disgrace over the Lockheed bribery scandal. Many Japanese remain convinced Tanaka was set up by political enemies to take a fall. His story, in some ways, invites comparisons with Donald Trump's first term, except Trump managed to avoid jail.

Finally, Shukan Shincho (February 27) featured five pages of dialog between two Showa-born authors: Hiroyuki Itsuki (1932) and Noritoshi Furuichi (1985). Last December Furuichi published a 344-page work of nonfiction titled Showa Hyakunen (Showa year 100, Kodansha, ¥2,310).

"While the war ended in the 20th year of Showa, the remainder of the era was twice that duration," Furuichi observed. To which Itsuki responded: "I live in the present and find it interesting. For better or worse, the Showa era is still around. As are many Showa people."

"Yes," Furuichi replied, "it doesn't look like Showa will be ending for a while yet. That said, Shukan Shincho magazine is also a Showa-style media. I wonder if it will continue to exist."

"Hmmm, who knows?" Itsuki said. "We're living in a time when what's ahead is unknowable."

Mark Schreiber was born in Showa 22 (1947) and came to Japan as a teenager in Showa 40 (1965).