Issue:

The making of a twitter documentary: The last wish of Mr. Hata

Using the strict limits of a social media platform to tell a long-form story means breaking new ground in grappling with technical, ethical and emotional issues.

From my chair by the door, I looked up from my camera across the barbershop at Mr. Hata as he sat in the barber chair, having his hair dyed. Mr. Hata wanted to look his best. He was in the last stages of throat cancer, and was preparing to meet his estranged son for the first time in over 30 years.

I had already taken a few dozen photographs of Mr. Hata since picking him up at his home that morning, and was using the waiting time at the barbershop to review them before making a selection to publish on my Twitter account. If all went well, over the next few days I would effectively be live tweeting an extremely personal and difficult story, something I had never done before. If it did not, my documenting could negatively affect the reunion while the Twitter verse looked on. With Mr. Hata not far from his deathbed, there would be no second chances.

Without the advice of an editor or a plan for how to tell the story things I usually rely on when working as a documentary filmmaker I began my first tweet: For the next 3 days, I’m going to tell you a story as it unfolds. It’s about family, love, life, death, and, I hope, redemption.

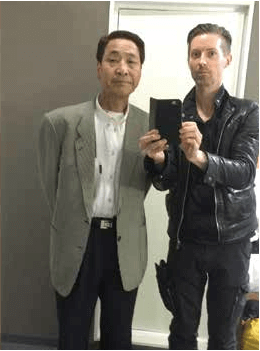

I HAD FIRST MET Mr. Hata five months earlier, while working on a documentary for NHK World called Dying at Home, about a home doctor in a small town in Tohoku. Mr. Hata was one of the patients, and I had grown quite close to him during production. I continued to visit him and his wife after filming was completed, often spending the night at their home. When I would arrive, they always greeted me warmly with a home cooked meal.

The couple had no children, but she still called him “father.” And when Mr. Hata would voice concerns about my lack of job security, and tease me for being too skinny and not being able to “drink like an adult,” he really seemed like a dad.

It was on one of my visits, when his wife was not around, that Mr. Hata told me that he had a son from a previous relationship. His name was T, and Mr. Hata had not seen him in over three decades. Now he told me that he wanted to see his son before he died.

Mr. Hata’s son has an unusual name, so I was able to find him through a computer search in only five minutes (and which is why for privacy reasons I decided to go with “T.”) A bigger challenge was getting a reply to my messages. I tried Twitter, Facebook and Instagram before finally hearing back from him. Not knowing what he’d been told growing up, I had debated about how to refer to the man who was searching for him. I settled on referring to him as “a man who says he is your relative,” accompanied by a photo.

T replied, saying that he had no memory of the name or face of the man, but that he would ask his mother. Adding to the difficulty, I had agreed to let Mr. Hata tell T that he was dying, so I was trying to impress upon him that time was limited without being able to tell him why.

At first hesitantly, eventually they began communicating directly. I was encouraged when I saw that T had tweeted the following on his account: Emailed father who abandoned me at 3. A film director found me. Thought he was dead, yet he’s alive. But he’s got little time left. Trouble sorting my feelings.

Plans for a reunion soon followed.

SHORTLY BEFORE THEY WERE to meet, Mr. Hata said to me almost teasingly, “You want to film our reunion, don’t you?” Not wanting to alter their time together, I told him that I’d let them have their privacy and hear about it later. But just prior to the day of the event, I received a call from Mr. Hata. He had become much weaker and could no longer drive. He needed someone to help with his carefully planned agenda, to pick up T and his family at the station and take them all up to a hotspring resort for the weekend.

While I felt saddened hearing of the loss of his independence, I was also grateful for the opportunity, since I felt an enormous responsibility as the one who had “found” T. And to be completely honest, I must also admit that a part of me thought it would be a real opportunity. I boarded a bullet train and headed for Tohoku armed with two cameras one for film and one for photos.

In the two weeks since I had last seen him, Mr. Hata had become visibly weaker. Still he insisted on following the itinerary he had planned, including staying at different hotels and visiting several tourist spots. It became clear that it would be impossible to film while helping out. At the risk of sounding insensitive, while not attending the reunion would have been hard, being there but not being able to film felt like torture.

I don’t exactly remember where the idea to “live tweet” the reunion came from, but it was definitely a Plan B after filming. Live streaming was another idea, but that would have been exploitative, too much like reality TV. With Twitter, choosing photographs and written words would give me the ability to curate which moments I shared and offer context that a live feed couldn’t, yet still lend the kind of immediacy and inclusion that audiences these days desire.

Whichever platform I chose, I was aware that there were ethical questions concerning the posting of the reunion in real time, and I knew if I made any major missteps along the way that there was the strong possibility of a harsh backlash.

The morning of the reunion, I explained to Mr. Hata as simply as I could he did not use social media or a computer that I wanted his permission to photograph and share the reunion with my followers. He agreed to allow me to do this up to when we would meet T, but I would need his son’s permission after that. Without knowing whether I would end up leaving my readers with a frustrating cliffhanger, I started tweeting.

AFTER DECIDING TO FOCUS on photographs rather than video, the next issue was how to live tweet the photos. For higher quality use in the future, I wanted to use my proper still camera, but there was no way to easily transfer the photos to my phone or iPad in real time. In the end, I decided to shoot twice: once with camera, once with phone. For shooting with the phone, I used an app with a silent mode to minimize any disturbance of the environment (in Japan, phones are required to emit a sound when photographs are taken). In the end, nearly all of the photos I published over the three days were taken with the phone, with almost no editing.

Another technical issue came up in a comment from a follower on Twitter, saying that it was difficult for viewers who became aware of the story in the middle to find out where to begin reading. Someone suggested that rather than sending individual tweets I post all the follow up tweets as a “reply” to my first tweet so they would remain in one chronological strand. (Later I found out about Storify, where tweets and other social media can be curated into a single piece.)

The only gauge for knowing if I was telling the story in a way that people would react to was the response from Twitter followers. The first one I received was about six hours after my first tweet, when AP reporter Yuri Kageyama tweeted to her followers: Amazing Tweets. This is what Twitter should be about. Follow Ian #ShoutOut for a universal story. A personal story.

Around the same time, a filmmaker friend living in Istanbul wrote to say how affected he was by the story and how it was causing him to reflect on his own relationship with his son. Encouraged by these comments from respected colleagues, I headed to the station with Mr. Hata to meet T, who gave me permission to continue the photo documentary, with the sole caveat that I not publish photos of his wife and daughter.

With film-making, you only learn about the audience’s reception a year or more after it is made, but in this case the reaction was instantaneous. It was thrilling, nerve-wracking and humbling.

So I was able to tweet their reunion as they got to know each other again. After dinner, Mr. Hata invited T back to his room for drinks where they had an intimate, and sometimes difficult conversation. Mr. Hata told T about the last time they had spoken on the phone: T was around five years old and he had pleaded with his father to come home. “Please come back, daddy!” he’d said. “I’ll wait for you one trillion ten thousand years!” Mr. Hata looked at T. “Having kids is easy, ” he said. “Raising them is not.”

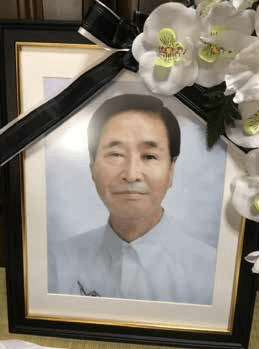

THERE WERE OTHER EMOTIONAL episodes over the next few days: The photo I took of the two of them under some cherry blossoms the first to catch them both smiling; the time they spent looking over photos as Mr. Hata asked T to choose which one should be displayed at his funeral; when I asked T to help me wake Mr. Hata from a deep sleep, and he gently placed his hand on his shoulder and called, “Father.”

One night after Mr. Hata went to bed, I shared with T some of the enthusiastic comments the story of their reunion was receiving from people all over the world. With film making, you only learn about the audience’s reception a year or more after it is made, but in this case the reaction was instantaneous. In real time, people were sending words of encouragement and T and I were able to immediately respond with words of gratitude for their support. It was thrilling, nerve-wracking and humbling.

Reactions from around the world flooded in and my follower count soared. Compared to an average month, the engagement rate on my Twitter account doubled that month and statistics for retweets, likes and replies went up an average 10 fold. I became more conscious that what I was producing was being “consumed.”

This affected how I told the story, such as how much personal information I chose to share with the public. I consciously decided not to use their full names, the names of the places where they live or even the circumstances under which the father and son were separated. And yet, because of the personal nature and immediacy in how I shared the story, I think most readers did not realize how much was not shared and instead were simply engaged in the story.

Which leads to another issue: how much to share what you are doing with your subject. Generally speaking, I would suggest that having your protagonist be so aware of the documenting process could negatively affect what it is you are documenting, so while I would encourage the filmmaker/ journalist to be honest about what they are doing, I would also discourage them from sharing how their story is being received while it is still happening. That being said, I think one of the reasons T was so open and seemingly unaffected by the whole process was because he is a writer himself.

AT THE RISK OF sounding overly dramatic, the adrenaline rush of live tweeting this reunion between a dying father and son was thrilling in a way that I have seldom felt when filming an interview when I know that I can always rephrase my question, and that there will be time to edit and refine the story. But I would also caution against telling a story utilizing this method simply because one “wants to.”

There is a most appropriate way to tell every story; and only certain stories truly lend themselves to being told in real time on a public platform such as Twitter. As story tellers, we must be aware of the potential damage we could cause to the people we are documenting and must proceed with caution, understanding that once something has been tweeted, it cannot be undone.

After the reunion with T, Mr. Hata’s health continued to decline. I traveled between Tokyo and his home in Tohoku as much as possible, shooting film as well as just being with him. My role had already evolved from filmmaker to friend, and during the last week of his life, I became one of his caretakers, helping to bathe and care for him.

I also continued to tweet the story of Mr. Hata until, three weeks to the day of his reunion with T, he died in his sleep.

Ian Thomas Ash is an award winning documentarian based in Tokyo who is in production for two documentaries, one about terminal care in Japan and the other the third installment of his series on Fukushima post 3/11. His tweets of Mr. Hata’s last wish can be seen at https://storify.com/DocumentingIan/mr-hata-and-t-a-reunion-after-30