Issue:

October 2024

One year after Hamas’ attack on Israel, Japan’s media are ignoring the public’s nuanced feelings about its aftermath

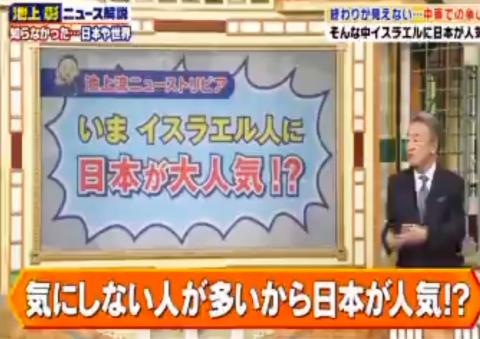

In an August 17 broadcast of TV Asahi’s Ikegami Akira no Nyūsu: Sōdatta no ka (Akira Ikegami’s News: I See, So That’s How it is!), popular TV commentator and author Akira Ikegami told the show’s panel a surprising fact: since the October 7, 2023, attack on Israel by Hamas, Israeli tourism to Japan has not only continued, but increased.

Beginning with Israel’s military response to the attack, Ikegami informed the panel: “In Gaza, civilians have been dying in large numbers. Because of this, there have been rising denunciations of Israel [in Europe]. So, if Israelis go to a hotel in Europe, and show an Israeli passport at the hotel, just because of that, they might be treated harshly. Because ‘they came from a country that is killing Gazans,’ or such ... There has long been anti-Jewish sentiment in Europe … But, by the way, because Japanese people, by and large, have no such feelings, if an Israeli person comes to Japan, even if they show an Israeli passport, nobody has any reaction.”

Ikegami then offered, seemingly in relation to the segment’s opening footage of the war in Gaza and global protests against it: “I don’t know whether this is something to celebrate or not.”

Almost a year after the attack, street interviews with half a dozen Israeli tourists on the TV Asahi program offered a stark contrast not only to the initial dissatisfaction of pro-Israel voices inside and outside Japan’s to Tokyo’s diplomatic response, and to criticism among Japanese intellectuals, journalists, and politicians of the humanitarian crisis in Gaza portended by Israel’s military response.

Major bookstores in Japan are now displaying titles about the conflict and its history, mostly by academics or former diplomats and aimed at a general audience. Often labeled Paresuchina mondai (the Palestinian problem), these displays are at variance with TV Asahi program’s notion of a Japan void of criticism of Israel. Rather, most recent works have been sharply critical of Israel.

So, to what degree do the Israeli tourists cited by TV Asahi program provide a window into trends in how the Hamas-Israel War is being discussed within Japanese society?

To begin, surveying Japanese media’s coverage of the ongoing conflict and humanitarian crisis in Gaza, a more complicated picture emerges.

Some examples of coverage over the past year dispel any notion that Japan’s media has neither covered the war nor been critical of Israel:

On November 10, 2023 (the anniversary of the Nazi pogrom Kristallnacht), the Asahi Shimbun’s front-page editorial Tensei Jingo asked: “Do the Jewish people intend to repeat their negative history, even though they have experienced indescribable suffering?”

On January 7, 2024, TBS TV’s Sunday news magazine, Sandē Mōningu, used special effects to morph a section of the Gaza border wall into a wall at the Auschwitz death camp, with an announcer declaring, “But Israel, which created this wall, was once in the opposite situation.”

In an October 18, 2023, article for the weekly magazine SPA, Professor Akari Iiyama (a candidate in this year’s lower house by-election in Tokyo for the newly formed Conservative Party of Japan), lamented that the Japanese media had been sympathetic to Palestinians. She argued that the issue should be discussed “from the standpoint of protecting Japan’s national interests”.

Related to the above, over the past year several events in Japan have received both domestic and international coverage not because they reflect a Japanese unawareness of the conflict between Hamas and Israel or the situation in Gaza, but rather the opposite.

First, English and Hebrew-language media reported in June that an Israeli tourist had been refused hotel accommodation in Kyoto on account of his nationality. The hotel's manager – who himself is not Japanese – reportedly told the tourist: “We are not able to accept reservations from persons we believe might have ties to the Israeli army … offering lodging to persons who might have assisted or might be assisting in the execution of warfare activities forbidden by international humanitarian law based on the Geneva Conventions. (Ynet, June 18)

The Israeli Embassy in Japan vigorously objected, and the hotel soon received verbal and written reprimands from Kyoto city officials. Kyodo News reported that city officials had clarified that the reasons cited by the manager for rejecting the Israeli’s booking were “… not a legitimate reason for denying accommodation”. Foreign Minister Yoko Kamikawa asserted it was “unacceptable” for a hotel to deny accommodation on the basis of national origin.

While the instance suggests at least some negative sentiment toward Israelis in Japan, the Israeli news outlet Ynet on June 19 offered the headline: "Japanese 'disgusted' by Kyoto hotel barring Israelis, ambassador says."

This was at odds with the Los-Angeles-based human rights organization, the Simon Wiesenthal Center (SWC), whose assessment framed the incident as “antisemitic” in a June 25 letter to the Japanese ambassador to Washington. As opposed to the SWC’s assessment, Ynet’s Itamar Eichner wrote: [Israeli Ambassador to Japan Gilad] Cohen told Ynet that the incident at the Kyoto hotel did not reflect Japan's overall attitude, which has been welcoming and appreciative of Israeli tourists. “There is no antisemitism in Japan,” he said. “There is a strong desire to host Israelis, and the El Al flights to Tokyo are full. This incident is an outlier.” (Ynet, June 19)

Secondly, Nagasaki Mayor Shiro Suzuki decided not to invite Cohen to the city’s ceremony marking the 79th anniversary of the atomic bombing, citing a desire to “avoid disturbances”. In an August 5 interview with CNN, Cohen argued that the security concerns were merely “an excuse”. “It has nothing to do with public order … I checked it with the relevant authorities that are responsible for public order and security, and there is no obstacle for me to go to Nagasaki,” he said.

Outside Japan, some pro-Israel organizations such as the American Jewish Committee and the Zionist Organization of America panned Suzuki’s decisions as detrimental to Israeli-Japanese ties. Suzuki’s move drew condemnation from the other G7 countries, whose ambassadors then boycotted the event. However, Hiroshima invited Israel to its annual commemoration on August 6, as it had done in previous years. Outside the memorial event, there was a protest against Israel and the presence in Hiroshima of its ambassador.

Suzuki said that Nagasaki officials were worried about “unexpected situations” that could disrupt the event, which Israeli diplomats had attended for years. In a profile of Rabbi Abraham Cooper, associate dean of the SWC, the conservative Sankei Shimbun highlighted that Cooper and two advisers to the center had written, in a Jerusalem Post editorial, that a “different and unfair standard” was being applied to Israel. The Sankei wrote in an August 8 article: “The first statement [by the SWC], dated June 25 [2024], points out that antisemitism is spreading in Japan. As an example, the statement cited the decision of Nagasaki City [to not invite Ambassador Cohen].”

Whether the celebration Suzuki’s decision or condemnation of it, media reports have tied the decision to a much larger Japanese public sentiment, with no clear evidence.

For example, online reaction in Japan to Hiroshima’s August 6 ceremony marking the 79th anniversary of the U.S.’s atomic bombing of the city, praised the Hiroshima government and public broadcaster NHK for supposedly criticizing Israel when in fact, neither had seemingly offered criticism.

As Hiroshima’s governor, Hidehiko Yuzaki, delivered a part of his speech, NHK cut to a camera shot of Cohen at the moment Yuzaki remarked: “At present, we still see wars in various parts of the world. The strong defeat the weak. The weak are trampled down. In contemporary wars, men and women, young and old, are shot by bullets or torn into pieces by missiles, rather than by arrowheads and swords. Great powers, which are expected to protect international order established by the United Nations, overtly attempt to invade other countries by violating international laws and changing the status quo by force.” (Yuzaki Hidehiko, quoted in Mainichi Shimbun, August 6, 2024)

Within hours, the hashtag #IsuraeruTaishi (#IsraelAmbassador) was trending on X, with Japanese posters overwhelmingly positive towards – and in many cases, praising – not only NHK, but Hiroshima’s government. Some even asserted that the Hiroshima government had invited Ambassador Cohen for the sole purpose of having him hear Yuzaki’s anti-war remarks.

There is nothing to indicate that the Hiroshima government or Yuzaki intended anything of the sort. The existence of a supposed intent within Yuzaki’s speech offers a poignant example of how the media are using isolated events to claim that Japanese public opinion is monolithic.

Taking the TV Asahi program together with these other events, we find a great deal of commentary has been devoted to what a homogenized Japan thinks about Gaza, Israel, and Palestine. This viewpoint is not particularly new. For instance, independent of one another, Japanese academics Akifumi Ikeda and Tetsu Kohno, both published 1987 papers arguing that Japan had a singular “pro-Arab” slant that was shaped directly by Japanese foreign policy. Over the past year, foreign publications from the Jerusalem Post to the Diplomat have similarly conflated everyday Japanese citizens’ views with purported shifts in Japan’s foreign policy.

Rather than trying to chart the nuances of how Japanese citizens view the ongoing war, frequent and persistent assertions of a homogenized, monolithic Japan in media coverage this past year stand to tell us much about the ongoing political utility of a fanciful and outmoded image of Japan. To speak of Japan in such a homogenizing manner calls to mind French critic Roland Barthes, who in 1970 who issued a provocative and sardonic dismissal of Orientalist writing about Japan:

“If I want to imagine a fictive nation, I can give it an invented name … I can also – though in no way claiming to represent or to analyze reality itself … isolate somewhere in the world (faraway) … and out of these features deliberately form a system. It is this system which I shall call: Japan”. (From Richard Howard’s 1983 English translation, page 3)

Whether a Japanese NGO donating an ambulance to Israel (as chronicled in a July 20 piece by the Jerusalem Post), or Japanese and Jewish university students protesting against Israel in Tokyo and Hiroshima, it is clear that no singular perspective exists in Japan concerning the Hamas-Israel War and humanitarian situation in Gaza.

Dylan O’Brien is a PhD Candidate in Cultural Anthropology at the University of California, San Diego. His research examines how representations of Jews and Judaism in Japan interact with Jews living in Japan.