Issue:

October 2024

Six decades before Sho-Time, Masanori Murakami’s groundbreaking debut in MLB was the start of Japan’s assault on American baseball

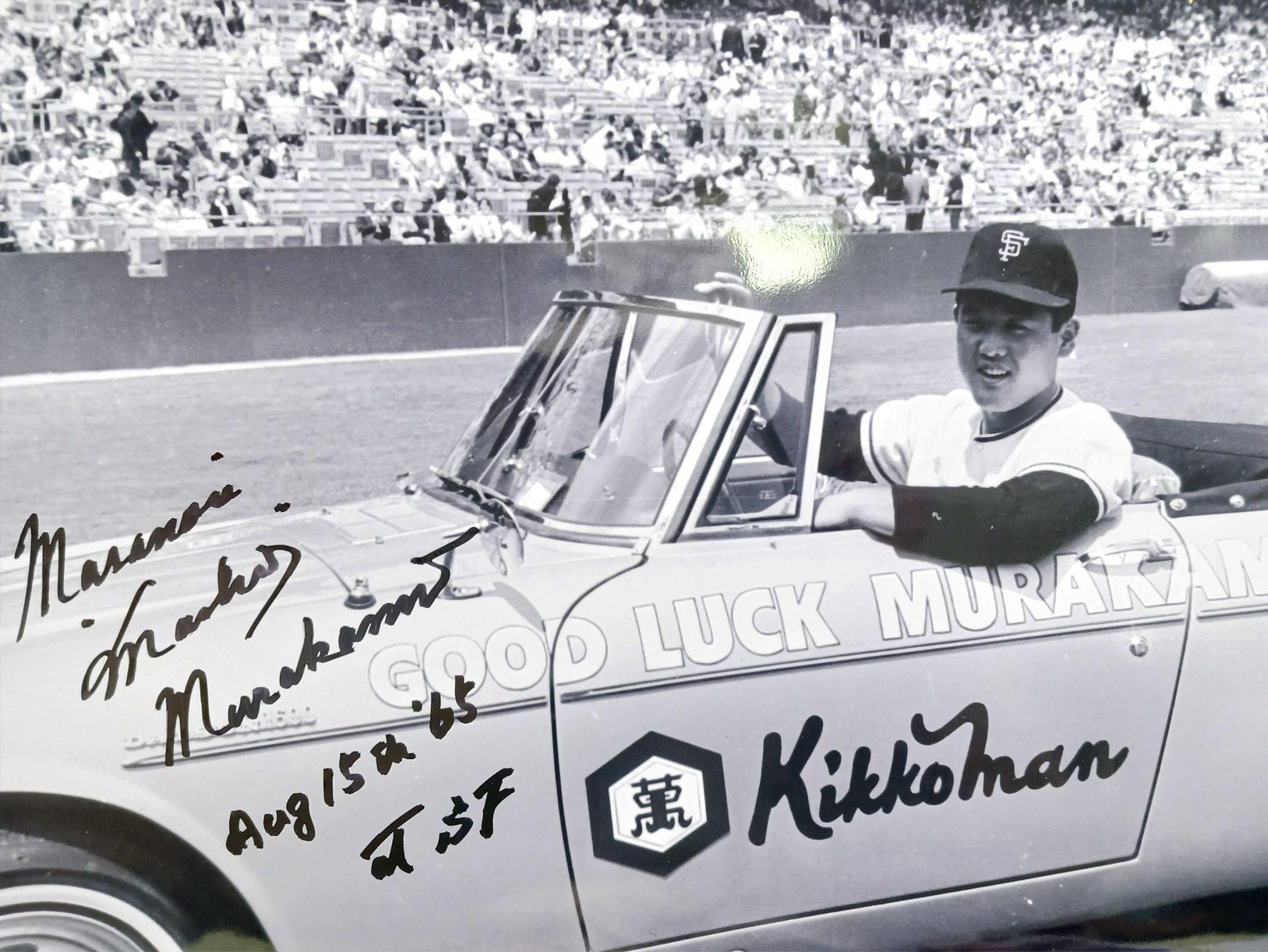

It was late in August 1964 in Fresno, California, when a 20-year Japanese man received a call to hop on a plane and go to Shea Stadium in New York City. Left-handed pitcher Masanori “Mashi” Murakami was about to make history.

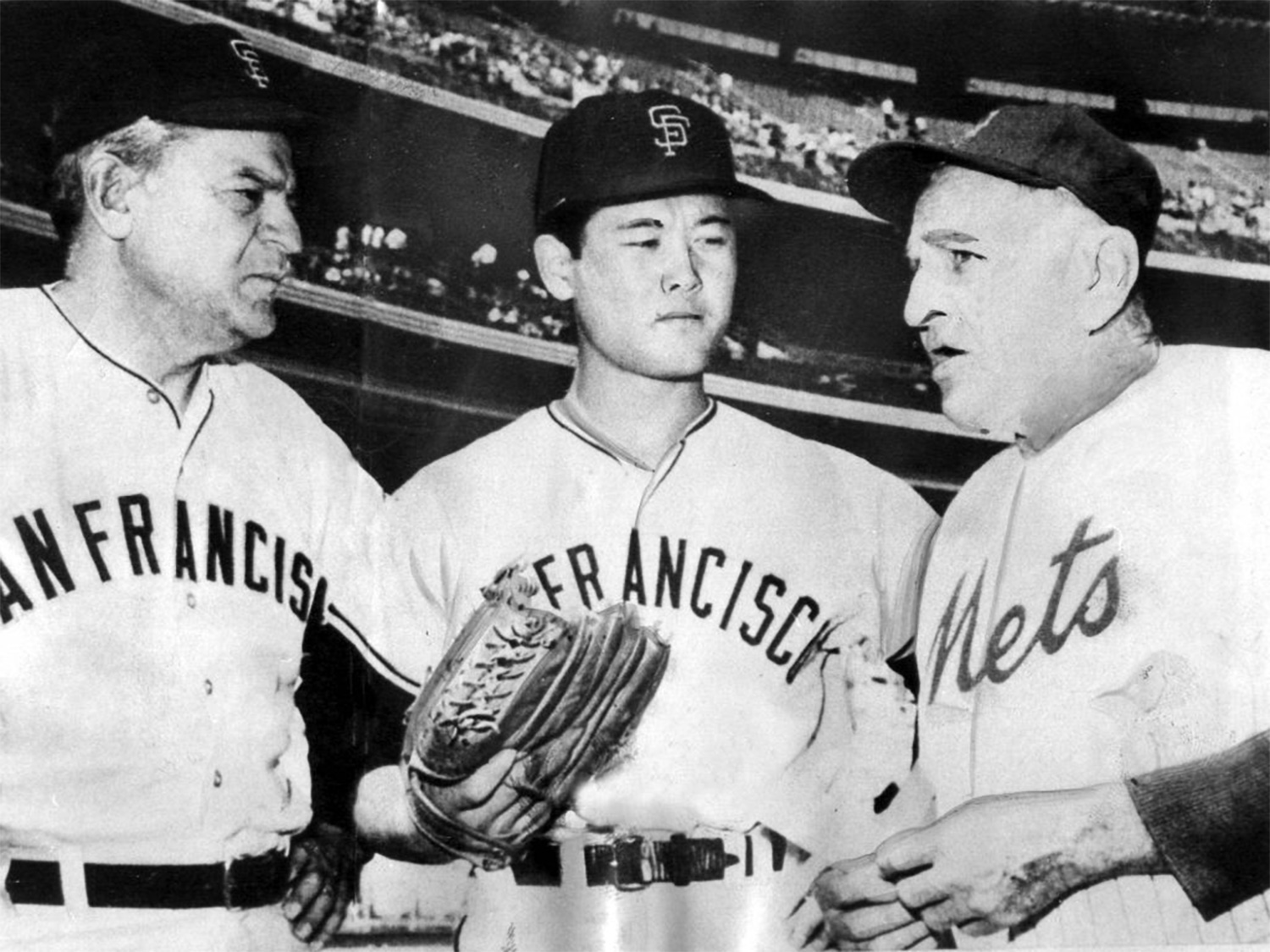

No Japanese had ever played in Major League Baseball (MLB), so Murakami’s ninth-inning debut for the San Francisco Giants against the New York Mets on September 1 that year made headlines. He struck out two and allowed no runs, later adding a win before the Giants’ season ended.

“It was a huge confidence boost,” said author and Japanese baseball expert Robert Whiting. “The game was reported on the front pages of the major sports dailies every time he pitched.”

His success prompted the Giants to rethink his planned return to the Nankai Hawks but Japan’s baseball commissioner intervened and said Murakami could play one more MLB season before returning home. After his valedictory season ended in 1965, a Japanese would not appear in an MLB game for another 30 years.

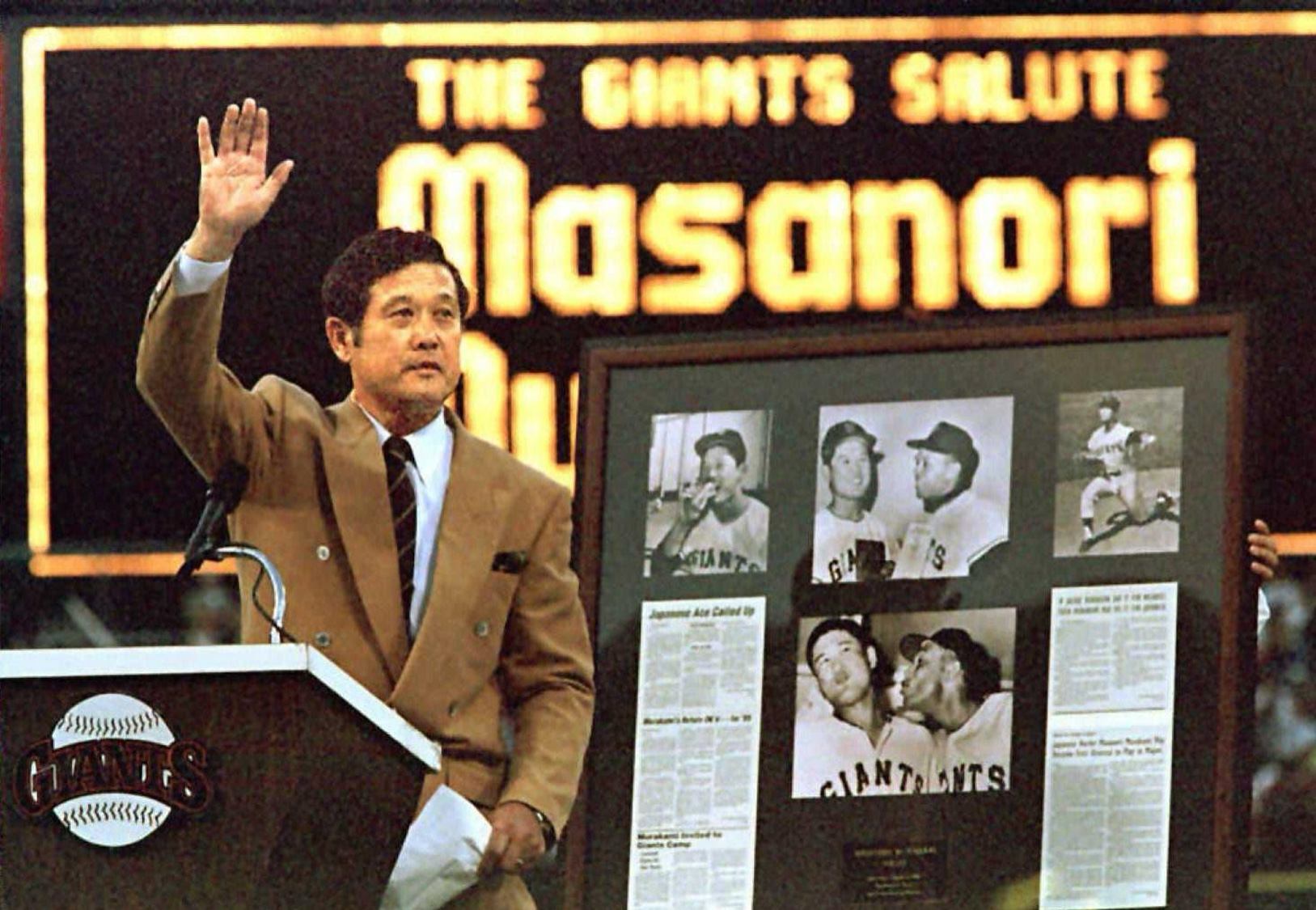

Murakami was part of an exchange agreement in which the Hawks sent players to the Giants’ farm team, although he was the only one to make it to “The Show” – American baseball’s big time. During his brief MLB career, the Yamanashi Prefecture native posted a 5-1 record with 100 strikeouts, 3.43 ERA, and 0.99 WHIP.

“It was unfortunate I had to come back to Japan, but I kept my promise to (Nankai manager Kazuto) Tsuruoka,” Murakami said at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan on the 60th anniversary of his pioneering moment. “If I had been able to play in 1966, I could have extended my MLB career five or six more years, because I was getting better.”

Murakami mastered the rare “screwball” pitch, which he honed under MLB Hall-of-Famer Carl Hubbell. His Japanese baseball career lasted until 1982, but Mashi’s brief MLB “cup of coffee” left deep concerns among Nihon Pro Yakyu (NPB) owners that if more local talent left, the home game could weaken beyond repair. This led to a contract agreement between the leagues in 1967.

“The 1967 US-Japanese Player Contract Agreement was a de facto embargo and shows you the impact Murakami had,” said veteran sports reporter Jim Armstrong. “Clearly, NPB didn’t want to lose talented players to the Majors.”

The pact chilled all Japanese exports until Hideo Nomo’s agent found loopholes.

“According to his agent Don Nomura, Nomo’s contract with the Kintetsu Buffaloes contained a clause saying he could not play for other Japanese teams, but nothing was mentioned about a U.S. team,” Murakami said. “That was a mistake I made.”

Whiting said Mashi could have benefitted from someone like Nomura. “A sophisticated agent would have been useful here, but the concept was too alien at the time.”

Nomo retired from Kintetsu to gain free agency to join the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1995, becoming an All-Star and Rookie of the Year.

In late 1998, a formal “posting” system was introduced requiring MLB to bid on Japanese players whose length of service allowed them to become free agents. This equaled the transfer fees that MLB teams would pay a Japanese team if it lost a player who had signed a U.S. contract.

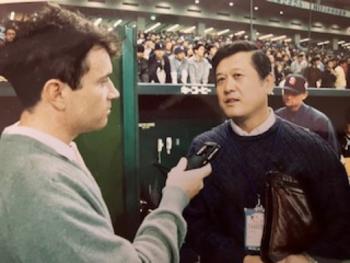

Murakami was at Nomo’s debut, which heralded a steady stream of Japanese pitchers across the Pacific, including Hideki Irabu, Mac Suzuki, Shigetoshi Hasegawa, and Masato Yoshii.

By 2001, position players were also heading stateside, including Ichiro Suzuki, Tsuyoshi Shinjo, So Taguchi, and Hideki Matsui. A total of 71 Japanese players have plied their trade in the Majors.

All eyes now are on the Chiba Lotte Marines’ Roki Sasaki, whose team will ultimately decide if he can join MLB due to his young age and inexperience. The coveted pitching prospect reportedly asked to go last offseason, but the Marines declined.

Despite posting system changes over decades, Japanese players still need lengthy service to become international free agents, and if under 25, are technically only allowed to sign minor league contracts, meaning less money for the Japanese team and player. If the team waits, there are no limits on his contract.

“It seems like (Sasaki’s) not having a good season … and it’s probably because of injuries,” Murakami said. “If he regains his form, he should be able to do very well in MLB.”

Looking back at his own debut, Murakami said he had signed his MLB contract 15 minutes before his first game. Multiple generations of Japanese stars did not get the same opportunity, he added. “Those former players at the top level of Japanese talent could have done well in the States. I was just lucky to advance to the Majors, but back then we had so many great pitchers … all those 300-game winners.

“MLB was literally out of our League, so there was no chance to compete with those guys.”

“Those guys” included Murakami’s Hall-of-Fame teammates Willie Mays, Orlando Cepeda, Gaylord Perry, Juan Marichel, and Willie McCovey. Pictures of his teams were on display at a recent exhibition highlighting his career and impact on baseball on both sides of the Pacific.

I first met Mashi at a U.S.-Japan All-Star Game in Tokyo in the 1990s, as speculation was growing that the best local nine could compete with MLBs’ finest. This was later confirmed when Japan won the World Baseball Classic three times, most recently in 2023. Shohei Ohtani, captain of the Japanese team, is widely seen as the greatest two-way player since Babe Ruth.

Armstrong said the consensus is that the exodus of Japanese talent began in 1995, but he believes its true origins lie in that evening in early September 60 years ago. “Nomo opened the floodgates, but it all goes back to Murakami’s brave move,” he said. “He truly was a trailblazer.”

Murakami also recognizes his place as the first Japanese and Asian player in MLB, debuting in an era without gargantuan contracts, personal translators, or Bobblehead nights. However, he cites Jackie Robinson, whom he met in 1965, as the true groundbreaker.

“I learned that he was a great player and person,” he said. “In Jackie’s case, he had a very hard time in MLB, because it was such a rough time with discrimination. It wasn’t that difficult for me.”

Dan Sloan is president of the FCCJ. He joined the club in 1994 and previously served as president in 2004 and 2005-06. He reported for Knight-Ridder and Reuters for nearly two decades.