Issue:

Olympiad that never was

Two years before the 1940 Games were scheduled to be held in Tokyo, criticism of Japan’s war in China led to a boycott movement

It was 2 p.m. on Saturday, Sept. 21, 1940, under sunny skies. The temperature was a balmy 23.2 degrees, with a brisk breeze. A multitude of 120,000 excited spectators who filled the just completed Komazawa Stadium to capacity turned their heads upwards to watch a formation of five newly built Imperial Japanese Navy Zero fighter planes soaring overhead, as they inscribed the five Olympic rings in blue, orange, black, green and red smoke on the sky.

As a military band struck up “Kimigayo,” the crowd rose as one to its feet, and 39 year old Emperor Hirohito, clad in full military regalia and flanked by his color guard, entered the track atop his white steed, Shirayuki.

Ascending to the rostrum, his majesty, in a reedy voice never before heard by his subjects, proclaimed to the 7,000 athletes and officials assembled from 58 nations six more than the 1936 event in Berlin “I hereby declare the opening of the 12th Olympiad!” The stadium reverberated with a chorus of “Banzai!” cheers.

THE ABOVE SCENARIO OBVIOUSLY never happened. It presupposes that prior to mid 1938, Japan’s military had substantially, if not completely, withdrawn from China. And, of course, that Germany had not invaded Poland in September 1939.

As it turned out, the Japanese government decided against hosting the games on July 14, 1938, and the 12th Olympiad of 1940 became what is now commonly referred to as Maboroshi no Orinpikku the Olympics that never were.

Tentative moves toward the selection of Tokyo as host began as early as 1929, when Swedish industrialist Sigfrid Edström, an organizer of the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm, visited Japan and discussed Tokyo’s prospects with Tadaoki Yamamoto, chairman of the Inter University Athletic Union of Japan. A year later Yamamoto, who traveled to Germany as head of Japan’s contingent to the International Student Games, was urged by Tokyo’s mayor to be Hidejiro Nagata to begin promotion efforts.

Nagata sought to host the games as a way of celebrating Tokyo’s recovery from the earthquake and fire that devastated the city in September 1923. In his view, the Olympics also would add window dressing to plans afoot the same year to commemorate the 2,600th anniversary of the ascension of Jimmu, the legendary first emperor of the Yamato Dynasty, an event that clearly had more enthusiastic support from the militarists in the government.

Japan’s representatives to the International Olympic Committee (IOC), Seiichi Kishi and Judo founder Jigoro Kano, were respected individuals passionately involved in amateur sports who worked tirelessly to promote Tokyo to their foreign counterparts. Another influential figure, Count Michimasa Soejima represented Japan at the general meeting of the IOC in May 1934, where he proposed Tokyo’s hosting of the event. The following year, Soejima, accompanied by diplomat Yotaro Sugimura, personally met with Italian prime minister Benito Mussolini to persuade Il Duce to withdraw Rome as a candidate city.

Although Japan’s incursion into Manchuria from 1931 had come under increasingly heavy international criticism, the IOC’s president, Belgian count Henri de Baille Latour, was predisposed to treat politics and sports as separate issues, and in July 1936, with Germany’s backing, Tokyo got the nod to host the games, with 36 votes to 27 for Helsinki.

THE ANNOUNCEMENT WAS MADE at the closing ceremonies of the 11th Olympiad in Berlin memorialized in Leni Riefenstahl’s film, Olympia when IOC President Latour addressed the crowd: “It has been decided that the next Olympics, in 1940, will be held in Tokyo.” After a brief hesitation for the news to sink in, the members of the Japanese contingent began shouting “Banzai!” with both arms raised. Athletes from other countries who were expecting to compete in Japan besieged Japanese team members, asking for home addresses so they could look them up four years later.

The news was quickly dispatched to Japan and by late the same evening, people carrying paper lanterns marched in celebration to the Nijubashi bridge outside the palace and to the Meiji Shrine. Long distance runner Kohei Murakoso, who had finished 4th in both the 5,000 and 10,000 meter events in Berlin, told the NHK audience by telephone hookup that he “would begin training for the Olympics to be held in his fatherland from tomorrow.”

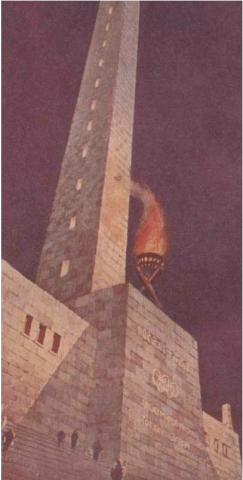

. . . or not. Opposite, a modernist Olympic tower planned for Komazawa Park that didn’t get built. (A tower did get built in the park for the 1964 Games.) Left, a woman presents the Games’ logo made from pearls.

On their voyage home, however, Japan’s athletes were served a rude reminder of the precarious political situation in Asia. When her ship visited Shanghai, swimmer Hideko Maehata recalled being told by the crew that conditions were in the city were “extremely dangerous” and their ship would weigh anchor away from the docks for security. The Japanese athletes were accompanied by an armed military escort while touring the city, and Maehata recalled thinking to herself, “Under these circumstances, an Olympics in Tokyo might not be feasible.”

Such concerns aside, planners moved forward with a schedule of events. The opening ceremony would be held at 3:00 p.m. on Saturday, Sept. 21, and the closing ceremony at 2:00 p.m. on Sunday, Oct. 6. A total of 20 events were planned: track and field, shooting, swimming, field hockey, water polo, fencing, gymnastics, soccer, weightlifting, basketball, wrestling, cycling, boxing, modern pentathlon, equestrian, art competitions, boating, martial arts, yachting and baseball. Soccer, rugby, tennis, polo, water polo, field hockey, handball, basketball and Basque style pelota (a relative of jai alai) were to be introduced on a trial basis.

THE MARATHON, SCHEDULED FOR Sept. 29 the final day of the track and field events would probably have followed a 42.195km route from the north exit of Komazawa stadium to what is now Kannana Dori at Daitabashi and making the mid point turn around in the vicinity of Inokashira park.

Three existing facilities still in use date back to the planning stages of the 1940 Olympics: Meiji Jingu stadium in Shibuya Ward, Baji Koen (Equestrian Park) in Setagaya Ward, and the Boating Course on the north bank of the Arakawa River in Toda City, Saitama. The Equestrian Park, a part of the Yoga district of Tamagawa Village, was actually established to celebrate the birth of the new crown prince on Dec. 23, 1933. Prior to then, no civilian equestrian facility existed in Japan.

The site of a golf course at Komazawa in Setagaya Ward was meant to be converted into an Olympic venue and to celebrate Jimmu’s ascension, but never got past the blueprint stage. (It was eventually developed for use by the 1964 games, and some of the facilities, now part of Komazawa Park, are still used for various sporting events.)

Jimmu’s ascension, but never got past the blueprint stage. (It was eventually developed for use by the 1964 games, and some of the facilities, now part of Komazawa Park, are still used for various sporting events.)

Meanwhile, unfortunately, the international situation was going from bad to worse. The sequence of events that led to the end of the 1940 games began on July 7, 1937, when Japanese and Chinese troops clashed at the Marco Polo Bridge southwest of Beijing.

Three months later the Japanese government established the “National Spiritual Mobilization Movement” as a part of controls on civilian organizations, including organized sports. As the flames of war rose and spread in China, the US and other countries began threatening a boycott.

Faced with a possible forfeiture, Japan backed out. A day after the July 14 announcement to the media, a vice minister of health and welfare curtly notified Tokyo Mayor Ichita Kobashi in writing that that “While it had been desirable for the 12th Olympiad to be held . . . current circumstances require full physical and mental effort be devoted to achieving objectives . . . and thus the games are to be halted.” The IOC’s first reaction was to transfer the games to Helsinki; but with the outbreak of war in Europe in September 1939, the 1940 Olympics were cancelled for good.

SO, INSTEAD OF THE glitter of the Olympics, Japanese sports fans were treated instead to the “Far Eastern Championship Games,” which commenced in Tokyo on June 3, 1940 as a rather pathetic replacement. About 700 athletes represented the seven participants: Japan, the Philippines, China, Man chukuo, Mongolia, Thailand and Hawaii. (The Hawaiian contingent was made up of ethnic Japanese). The 17 events were spread between June 6-9 in Tokyo and June 13-16 in Nara and Hyogo prefectures.

Aside from the loss of face, the drain on the Tokyo and national finances was considerable. An article titled “How much was wasted by cancellation of the Olympics?” that appeared in the Sept. 1, 1938 issue of Hanashi magazine, produced a rough calculation. These included the sending of delegations to Los Angeles and Berlin, ¥1.5 million; promotional outlays by Tokyo City, ¥3.5 million (Helsinki actually outspent Tokyo in a losing cause, paying the equivalent of between ¥4 to ¥5 million.) Setting up of the preliminary office in on the 4th floor of the newly constructed South Manchurian Railway Building in Toranomon, budgeted at over ¥3 million in 1937 and ¥4.5 million in 1938, of which only four months were utilized, so perhaps ¥130,000. Another ¥1 million was said to have gone into advertising and public relations activities. All together, the total outlay must have reached a staggering amount.

Another casualty was TV broad casting: Japan had hopes to follow up on Berlin, where experimental TV broadcasting had been introduced, to harness its own technology for coverage of the games.

Private businesses also suffered financially. Tokyo in 1938 had only 1,955 hotel and ryokan rooms deemed suitable for foreign visitors. Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel had issued additional shares of stock to fund a new 8 story wing, to be erected adjacent to its 280 room Frank Lloyd Wright edifice that opened in 1923 and the new wing would have boosted its total rooms to 500. The project was terminated. Designers were already concerned that with steel and concrete being diverted to the war effort, its construction would have been next to impossible.

More tragic than financial losses of course was the sacrifice of human lives, as many of Japan’s most acclaimed Olympians did not survive the war. 1936 pole vaulting bronze medalist Sueo Oe died during the invasion of the Philippines, and swimming medalist Shigeo Arai died in combat in Burma. Other casualties included swimmers Kiichi Yoshi, a pilot who was shot down, Yasuhiko Kojima, who perished in a banzai charge in Okinawa and Tomikatsu Amano, who went missing in action. The most famous of all, perhaps, was equestrian Baron Takeichi Nishi. An army colonel, he is believed to have committed suicide on Iwo Jima on March 22, 1945.

If you feel like mingling with the ghosts of disappointed Olympic fans from eight decades ago, you might want to stroll along a lonely section of Kaigan Dori in Minato Ward, where, sandwiched between the Haneda Monorail on the west and the Rainbow Bridge on the east stands Goshikihashi the “five color bridge” named for the 1940 Olympics that never was.

Mark Schreiber currently writes the “Big in Japan” and “Bilingual” columns for the Japan Times.