Issue:

WE ARE LIVING IN an

age when the president of the US commonly, if dubiously, called “the leader of the

free world says he would like people to admire him as the North Korean people do Kim Jong Un, the Supreme Leader of

a dictatorship. When in Britain, the lead candidate to head the governing party and become prime minister has been previously caught conspiring to have

a journalist beaten

up and has been demoted in government, sacked from a newspaper and even faced a court summons for his lies. When populist leaders from India to Brazil bathe in praise often of their own making.

Then, last month, the New York Times decided to completely stop all political cartoons. Yes, they can go too far, as did

one cartoon they published in April that strayed into anti semitism. It crossed the line of “speaking truth to power” and into an area where the power of previous cartooning had removed truths. While aiming to show Israel’s influence on

President Trump, it pictured Israel’s prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu as a guide dog leading a blind president only Trump was wearing a yarmulke, suggesting he had converted to Judaism, not Israeli politics.

Yes, the idea of Jews as dogs has an appalling history. But that’s what editing is for to guide, change or cut. The failure of an editorial staff to do its job should not be a reason for a blanket stop on publishing anything, including cartoons.

The art of the political cartoon lies in the ability to summarize an issue, to burst established bubbles and expose underlying intentions and characteristics. As UK cartoonist Martin Towson wrote after the Times’ decision, political cartoons have “the power to shock and offend. That, largely, is what they’re there for, as a kind of dark, sympathetic magic masquerading as a joke.”

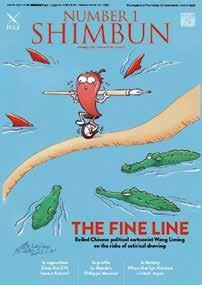

We don’t have a cartoonist in Number 1 Shimbun. But there is a reason that the Chinese cartoonist Wang Liming, who had exiled himself to Japan, made our front cover in February 2015: he was concerned for his safety and freedom if he continued making cartoons in China.

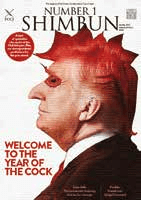

At times, however, our covers have used a thought process similar to that of a political cartoonist such as the November 2015 cover of the Asahi Shimbun folded into a paper boat and

bombed; the start of the 2017’s Year of the Rooster referencing the strutting nature of the US president in cartoonish form (with extra double meaning); or a visual comment about the safety of Japan’s new

seawalls on the March 2016 cover.

Our Trump cover was not necessarily universally liked. To some extent that is the effect of a political cartoonist. The power of a good piece of art might test the boundaries

of lampooning those in power. Or, perhaps, the boundaries of social-media voices, which can gather individually to express a collective outrage.

The cartoonists of the French satirical publication Charlie Hebdo can get too close for comfort on issues of racism or religious freedom even occasionally cross the line, some might justifiably argue. But their aim is to nonviolently burst the bubbles of power and the powerful with their art, not to be part of a world where five of their staff can be slaughtered in their offices for their views.

At a time when many hundreds of thousands of people are marching in Hong Kong, some hoisting placards of the city’s Chief Executive pictured

as a devil, and many protesters in the UK are competing to make the most pertinent and pithy placard about politicians and Brexit, it seems exactly the wrong time to be stopping political cartoons. If anything, they as any medium seeking to challenge opaque and misused power are needed more than ever.

– Andrew Pothecary

Andrew Pothecary is the art director of Number 1 Shimbun.