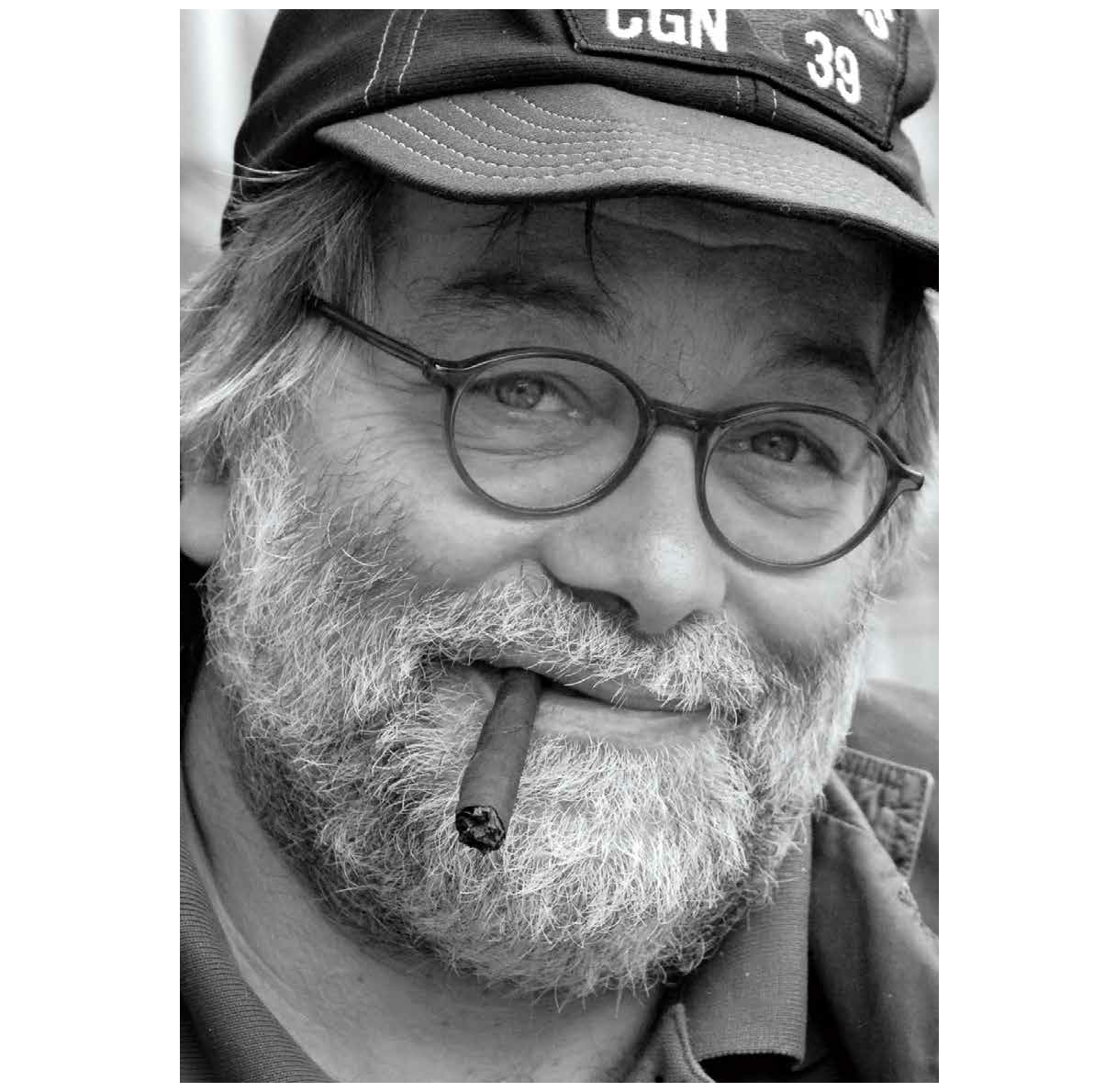

Issue:

The humble necktie.

It was this small sartorial requirement that Pio d’Emilia maintains was one of the decisive factors that swayed him away from the legal profession and into the media. “As a journalist you can you can live in the same world as lawyers, but don’t have to wear a necktie,” says d’Emilia. “I just hate them. Even now I only have three or four, and they were all gifts.”

Japan was also a major reason, he concedes. He became captivated during his first visit to the country in 1979 by the lack of rights for detainees, the thesis subject for his legal studies back in Italy. “I was interested even in the rights of terrorists and I was interested in the Red Army Faction. I saw the interrogations and detention cells used by the police in Japan.”

Having been given permission to witness a police questioning, d’Emilia recalls being puzzled at the large number of people in the room. “There were eight people, a prosecutor, police etc. I asked where the lawyer was and was told there was no lawyer; I was so shocked. So I asked how long someone could be held without access to a lawyer.”

D’Emilia recalls that due to his nascent Japanese ability at the time he misunderstood the answer as 23 hours. Upon realizing it was actually 23 days, he “nearly had a heart attack,” he says.

He contacted an editor at the Italian magazine L’espresso with the idea for what would become his first article, quickly followed by “something about Nissan.” He says, “That was the turning point from Pio d’Emilia troublesome lawyer to troublesome journalist.”

Despite the disapproval of his mother he hailed from a family of lawyers he returned to Italy to study journalism, then returned to Japan in 1982. D’Emilia spent a few years covering the People Power Revolution in the Philippines, where he would later receive a medal from the victorious President Cory Aquino, though not for his journalism. “I saved one of her friends by getting them through a checkpoint of [Ferdinand] Marcos’ men. I had borrowed a diplomatic car from a friend and used that to get through.”

Five years in Rio de Janeiro followed, where he covered the whole of South America, before returning to Italy and a stint teaching contemporary Japanese politics at Rome University. This led to him getting involved in Italian politics and the efforts of Romano Prodi to end the stranglehold of the Christian Democrats on power. When the Democratic Party of Japan was formed in 1998 with the intention of doing the same to the Liberal Democratic Party’s dominance, d’Emilia moved back to Tokyo to work as an advisor to Naoto Kan. “Being very interested in social issues, culture and politics, rather than economics, I see many similarities between Japan and my country: awful, corrupt governments and great people.”

I see many similarities between Japan and my country: awful, corrupt governments and great people.

After Kan was, he says, “lured in a different direction by the nefarious Ozawa,” d’Emilia returned to journalism in 2000. He remains a staunch defender of Kan and believes his treatment at the hands of the Japanese media when he was prime minister during the triple disasters of 2011 was “terrible,” when he should have been hailed as “a hero.”

Over the last decade reporting for SKY TG24 TV, d’Emilia has covered the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004, the Tohoku tsunami of 2011 and the typhoon in the Philippines in 2013. He found the most recent of the three the hardest to handle: “It was seeing the rotting bodies, many of them children. When I arrived in Tohoku the bodies were mostly already covered up.”

Officially based in Beijing for the last three years, d’Emilia has kept his apartment in Tokyo and travels between the two as the news takes him. The situation for foreign journalists in China has improved a lot in recent years and he says he now has “absolutely no problem in general reporting and access to people,” though there are still certain taboos such as religion, dissidents and human rights beyond a certain point.

“I’m an optimist on China and pessimist on Japan, ” he says, predicting that China will take over Europe economically, while Japan will “put itself at risk” through the historical revisionism of Abe and his allies. So convinced is he of the certainty of China’s rise that d’Emilia, who speaks five languages, persuaded one of his six children to learn Mandarin to fluency.

D’Emilia’s personal life seems to have been as colorful and varied as his professional one. “I’ve had six kids with five different women and am very proud we’ve never had a court case. We’ve managed to keep this loose, enlarged family together without resorting to suing each other. Despite having made a mess, it’s not a chaotic mess. Every year we get together in summer and at Christmas, all the kids and some of the mothers.”

Still with the mother of his youngest child, d’Emilia notes, “if a Burmese monk’s prediction comes true, I’ll have one more kid.”

Having recently turned 60, and with retirement somewhere on the horizon, d’Emilia says his thoughts have turned to doing “some more serious things.” This has included a documentary, Nuo Gu In the Name of the Mother about a matriarchal society in China. He is also working on a docufiction titled A Nuclear Story Inside Fukushima, due out in the summer and partly based on his book, Nuclear Tsunami.

As for those neckties, he’s still not a fan. “Even now, I try to avoid them by wearing some type of ethnic dress for official parties.”

Gavin Blair covers Japanese business, society and culture for publications in America, Asia, and Europe.