Issue:

February 2022

Why the Katoku coastal defense plan will unleash environmental catastrophe

Adam Lewis - ©2019 Blue Pacific Media

Activist and Amami-Oshima resident Jean-Marc Takaki appeared at a press conference organised by the FCCJ in January to explain why he and others believe the plan to build a seawall along the island’s Katoku beach is misguided and will cause irreversible environmental damage. The plan, he said, would have a devastating effect on this beautiful bay.

Adam Lewis - ©2019 Blue Pacific Media

Takaki is a French citizen who has been living in Japan for many years and has Japanese nationality. He is currently the director of an association for the protection of Amami’s forest rivers and coastal ecosystem.

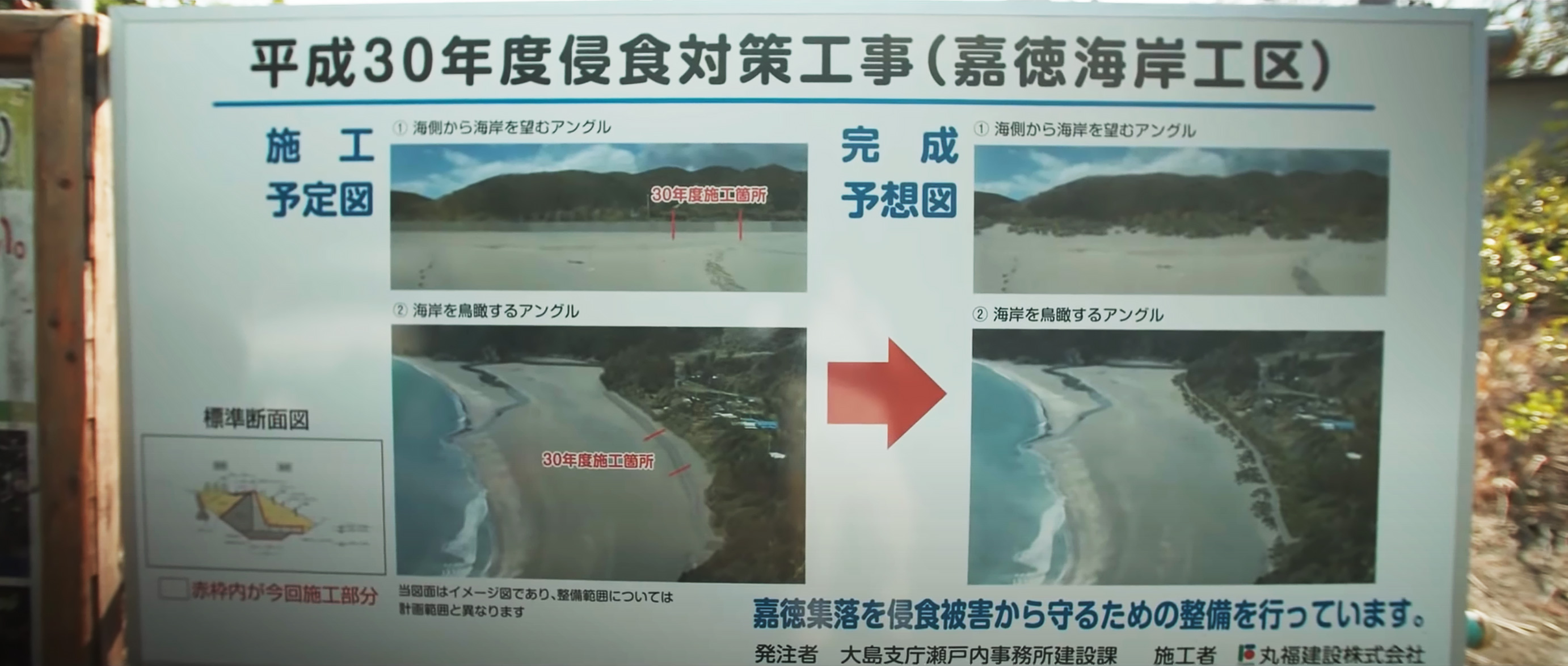

Katoku beach is located on the subtropical island of Amami-Oshima, one of the Ryukyu island chain famous for its scenery, rich ecosystem, and surfing. The government’s plan is to cover most of the beach with a 6.5-metre-tall, 180-metre-long seawall, which would replace the natural sand dune buffer, causing severe erosion and destroying the surfing beach.

Adam Lewis - ©2019 Blue Pacific Media

Takaki spoke calmly in his detailed presentation, illustrating it with photos of the beach at Katoku and the area behind, which encompasses the village. But he began by describing his own background and how he came to be a resident of Amami-Oshima. While living in France he visited Japan every summer for vacations and fell in love with the country, since his mother is Japanese and his father is French, and he had been coming to Japan regularly since a child.

He went on to describe a situation in which nearly all bays in Japan nowadays have seawalls with unsightly tetrapods often cluttering the beach. Examples of these were shown at Tategami in Karatsu and Takahama in Amakusa, where there is now no ocean view and very limited access to the shoreline, and at Nichinan in Miyazaki. These are all places Takaki had visited as a child.

After returning to France for three years, he decided to come back to Japan to live. It was then that he discovered what he described as a miracle – a bay at Katoku on Amami-Oshima with an isolated village, no seawall, and a meandering river estuary. “The beach is always alive and changing and the river flows sideways,” he said, adding that he believed it was probably the last beach hamlet in Japan in a bay without a harbor, seawall or concreted river mouth.

Adam Lewis - ©2019 Blue Pacific Media

The biodiversity of Katoku includes over 400 species of shellfish, Ishikawa frogs, a type of shrimp, Amami black rabbits and the critically endangered leatherback turtle. “That alone should have been big news especially if they are to build a seawall on the only beach in Japan where a leatherback actually came to spawn,” Takaki said. “It’s something that should have been quite controversial but sadly this fact was hidden …the prefecture hasn’t done an impact study and our own studies have been ignored.”

He showed photos of concrete blocks already on the island that are supposed to go in front of the seawall.

Adam Lewis - ©2019 Blue Pacific Media

Sand-dredging offshore is also conducted to make concrete blocks because, ironically, most of them comprise 85% sand, Takaki said. “This process causes the erosion that they are using as a pretext to concrete the beach.”

Since the March 2011 triple disaster there has been an increase in plans to build seawalls for protection from tsunami, and the media in Japan tends not to cover these issues. Takaki said Kagoshima prefecture had sent a letter to the International Union for Conservation of Nature outlining the prefecture’s procedural failings and the impact the project will have on the local environment.

Adam Lewis - ©2019 Blue Pacific Media

In response, citizens have been doing their own research and holding symposiums, as well as planting pandanus trees. They have allegedly suffered widespread intimidation and harassment, often from construction workers. Takaki said someone had even threatened to slit his throat.

The prefectural government has refused to discuss the project and ignored petitions from villagers.

Takaki said he and other campaigners had tried contacting the Kagoshima governor, but the reply was always the same, with officials using the line, “We are protecting life and heritage” to justify the project and head off further discussion.

He speculated that one of the biggest Self Defense Force bases in the Ryukyu islands now being built overlooking Katoku means that the area would eventually be turned into a military harbour. To achieve that, he believes the authorities hope to depopulate the village and ensure the beach disappears so no one goes there for recreation.

Adam Lewis - ©2019 Blue Pacific Media

Takaki said the local village chief and mayor both support the seawall as they "depend a lot” on construction projects to push their re-election bids. Some villagers have even tried to stay out of trouble by signing petitions both for and against the seawall, he said, adding that even mentioning the word Katoku had become taboo among journalists. “This is where we are with the free press”, he said.

Watch the documentary A line in the sand: The fight to save Jurassic beach

John Potter is a professor (retired) at Kogakkan University, Mie Prefecture, and now lives in Okinawa. He is the author of The Power of Okinawa, about the region’s music.