Issue:

February 2022

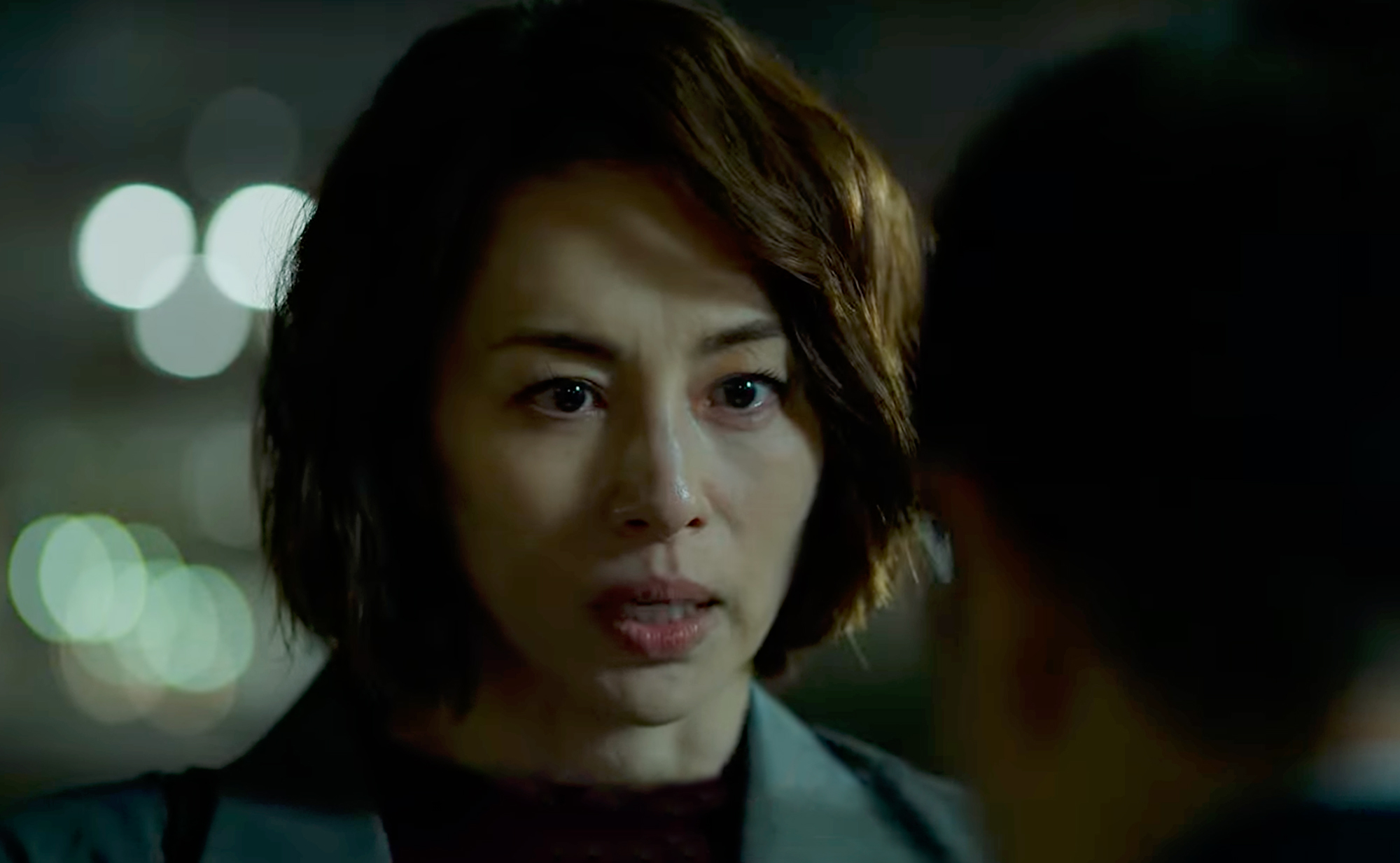

Netflix drama The Journalist hits uncomfortably close to home in its portrayal of Japan’s politics and media

At the end of a long week, I was sitting on a Yamanote Line train listening to Adele for a change of mood. Then I noticed three screens all showing an advertisement for the same TV drama - 新聞記者 (The Journalist) - currently being shown on Netflix. I was surprised, but also delighted. The series was getting publicity, even on the train.

Largely ignored by the big media companies, the six-part drama created a buzz on social media in Japan within a couple of days of appearing online. I binged five episodes in a single night, but decided to keep the final episode for the following day. I generally don’t have time to watch TV dramas, but I had to watch The Journalist. I’m glad I did.

It could have worked just as well as a purely fictional drama based around politics and the media, but its plot lines and characters mean The Journalist hits uncomfortably close to home. It follows Anna Matsuda (Ryoko Yonekura), a determined reporter for a newspaper during the latter part of Shinzo Abe’s eight-year prime ministership, which ended in the autumn of 2020,

Any journalist who has been covering political news in Japan in recent years will quickly recognise the drama’s real life backdrop – the Moritomo Gakuen land sale – and the main players in that scandal, including the prime minister - although he does no appear - his chief spokesperson, and bureaucrats in the finance ministry.

The details are different, of course, but the similarities are impossible to miss, not least in how the government seeks to quash the scandal in the face of questioning from lawmakers and the media, and the Machiavellian manipulation of local officials by their senior colleagues in Tokyo. We see subordinates pressured into crossing moral and legal lines in a desperate attempt to save the prime minister’s skin, with tragic consequences for those who initially cooperate but later examine their conscience.

Matsuda is based on Isoko Mochizuki, a journalist with The Tokyo Shimbun whose reporting caused frequent headaches for Abe and his chief spokesman (and successor as prime minister), Yoshihide Suga. "When I watched the government spokesperson's press conference, during which Matsuda is systematically snubbed and interrupted, but still insists on asking tough questions even though she is sometimes being mocked by her colleagues … it reminded me of how abnormal the real-life press conferences were,” Mochizuki said a few days after The Journalist went online.

“I’m happy that a fictional drama has faithfully recreated these scenes and that viewers in other countries get to see just how damaging the atmosphere is. The government spokesman - Yoshihide Suga at the time - had no respect or consideration for journalists like me.”

Her fictional character Matsuda is similarly pugnacious, dispensing with the conventions of Japanese reporting and convincing a skeptical university student that the mainstream media can be a force for good.

Matsuda’s refusal to give up came with risks, as it has for Mochizuki, who has been attacked on social media and sent death threats sent via her newspaper.

The Journalist is at its strongest when it looks at how shadowy forces use their power to attempt to change the narrative, whether by obstructing the work of prosecutors, setting up fake Twitter accounts or feeding “scoops” to favoured journalists.

At the heart of the power play is the Cabinet Intelligence and Research Office, which, according to the government, “plays a central role in the Japanese Intelligence Community, and provides insightful intelligence to the Cabinet to support its decision-making”.

In The Journalist, however, the office comprises automaton officials manning computers in a windowless room, constantly monitored by men whose sole aim is to protect the prime minister, and by extension themselves.

The narrative centers on Eishin Gakuen, the sale by the central government of property to the school at a dramatically discounted price, and the concerted attempt to cover up the discount through the falsification of official documents. There are clear parallels with Moritomo, a complex case that took shook Japan after The Asahi Shimbun reported the land sale in 2017. Five years later, the Moritomo scandal continues to generate headlines, and legal proceedings related to the suicide of a finance ministry official are ongoing.

The left in Japan has understandably embraced The Journalist, while the online right has attacked the drama on social media. Some pointed out that Masako Akagi, the widow of Toshio Akagi, the finance ministry local office bureaucrat who committed suicide after being ordered to falsify official documents, reportedly refused to cooperate with the drama’s producers and has been critical of Mochizuki. Akagi is now telling her story in “Ganbaryonkaa, Masako-chan” (Stand Firm, Masako), a serialised manga that launched in January in Big Comic Spirits.

Overseas reviews of The Journalist have been generally positive, although some reviewers do not appear to have grasped the drama’s real-life inspiration. In addition, some of the scenes are unlikely to make much sense to viewers who aren’t familiar with Japan, including one in which a character attempts to send a fax from a convenience store, neither of which exist in my country, France, for example.

For foreign reporters in Japan, it is those small details we recognise in our own daily lives, plus the significance of its commentary on the country’s politics and media, that make The Journalist a must-watch.

Karyn Nishimura is a correspondent for the French daily newspaper Libération and Radio France.