Issue:

June 2025

Remembering the first Osaka Expo, 55 years ago

(Second of two parts)

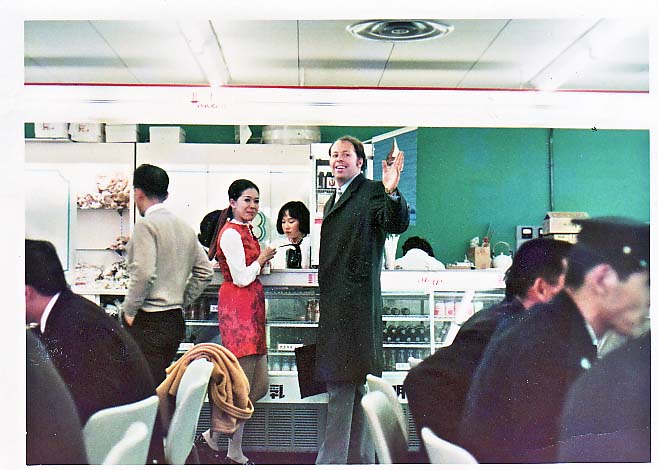

The Thai silk boutique I managed at Expo 1970's International Bazaar was loosely affiliated with the Thai pavilion, itself an inspiring example of Buddhist architecture. That pavilion was overseen by the Queen's cousin Mr. Kieatikhun Kitiyakara, who was accompanied by his famous wife, Apasra Hongsakula. Five years earlier Apasra had been crowned Miss Universe, the first southeast Asian woman - and the second Asian woman after Japan's Akiko Kojima in 1959 - to win the title.

Apasra's younger sister, Pavena, worked in our silk shop. She would later become a bank executive, and became famous in her own right after founding a humanitarian organization for women and children. She was also one of the first female ministers to serve in the Thai cabinet.

Except for bright colors like shocking pink, our Thai silk material was well received by Japanese shoppers, and the shop was kept well resupplied with a steady stream of air freighted merchandise. The Nittsu transport company handled our customs procedures and transported them as far as its warehouse, but charged extra for delivery onto the Expo site.

To cut down on expenses, our Japanese accountant, Ohara-san, arranged for the loan of a Daihatsu Hi-Jet mini pickup truck, a mid-1960s model which, its name's suggestion of jet speed notwithstanding, sported a woefully underpowered 356cc, 17 horsepower 2-stroke engine. The truck's cab was so small the only way I could squeeze in was by removing the entire driver's seat, which I replaced with a folded beach towel for a cushion.

Despite Osaka crawling with foreigners during the Expo, one day a local cop, perhaps curious at the bizzare sight of me crammed into the tiny truck's cab, flagged me down. I showed him my driver's license, which still carried my old Tokyo address from my student days. He then inquired: “Kore wa mai kaa desu ka? (Is this 'my car')?

Not being familiar with this particular English borrowing for a privately owned vehicle, his question left me mystified.

I replied. "Iie, anata no kuruma ja nai desu." (No, it's not your car), in a wounded tone of voice.

"Chigau, chigau. Kono kuruma wa mai kaa desu ka?” (No, no. Is this car 'my car')?

Again, I stood my ground. It was not his, no way … it was mine. Sorry officer, I don't know why you would even want such an underpowered rattletrap, and besides, I am not so well off that I can go around gifting motor vehicles to members of Osaka's finest.

After muttering “Wakarehen yaro na” (he doesn't get it) in the local dialect, he waved me on.

He probably thought "my car" was English, rather than wasei eigo. If he had asked me "Do you own this vehicle?" in proper Japanese I probably would have understood him.

Most of the staff at the foreign pavilions held diplomatic passports and tended to snub us lowly merchants at the International Bazaar. But we got along fine amongst ourselves, mainly because business was thriving and there was very little sense of competition. "Nihonjin wa nan demo kau!” (Japanese people will buy anything!) chuckled Nobuhiro Yoshioka, a flamboyant importer of curios from Nagoya. And he was right.

The International Bazaar was located close to the tour bus parking lot, and groups of farmers organized by nokyo (agricultural cooperatives) wearing plastic cowboy hats in a variety of pastel colors (to ensure differentiation when moving through crowds) transited the bazaar on their way home. Many dropped in to make hurried purchases.

As a precaution against pickpockets, older men were in the habit of stashing their bankrolls inside their haramaki (cloth belly band), occasionally causing our salesgirls to cringe at the sight of middle-aged farmers pulling open their trousers to extract ¥10,000 banknotes – often damp with perspiration – to pay for items.

The well-stocked and well-managed German shop, one of the most successful, was run by a German-Japanese couple, Knut and Chieko Netz. Knut, who turns 82 this year, still remembers his store's bestselling items: "We sold lots of Schwarzwaldpuppen (dolls dressed in traditional Black Forest costume), postage stamps – we assigned one sales clerk we nicknamed Kitte-san, just to sell stamps – and Solingen knives," he says. "In addition, I commissioned a German artist to design a coin that commemorated the German Pavilion at Expo, and they turned out to be a big sales hit."

Following the Expo, Knut spent many years in Japan representing Bavaria at trade shows and exhibitions. In 1980 he became my partner in crime, so to speak, when we spent a claustrophobic night at Japan's first capsule hotel, which I reviewed in the Tokyo Weekender magazine on January 16, 1981.

Among the other memorable individuals working at the bazaar was a young Indian man named Mitthu Melwani, who managed the Hong Kong shop. Mitthu's family had fled Sindh province in Pakistan at the time of the subcontinent's violent partition in 1947. The Melwani family operated a far-flung trading conglomerate and Mitthu, having been raised in Kobe, spoke fluent Japanese with a Kansai accent.

The Uruguay shop, managed by a bespectacled young diplomat named Guffanti, was skeptical that many Japanese would want to purchase his country's limited assortment of handicrafts, yerba mate tea and flamenco guitars. But during the first week, visitors descended on the shop like a swarm of locusts, leaving its shelves nearly bare.

Logistics being what they were in 1970, Guffanti had no plan for replenishing his inventory. The vendor contract, however, required that the store stay open, so Guffanti was obliged to sit in his empty shop all day with nothing to do but snarl and issue a stream of colorful curses in Spanish at anyone who wandered in. Eventually the Expo Association let him off the hook and Uruguay's space was rented out to another vendor.

Because Montreal had hosted the previous exposition three years earlier, Canada was particularly well represented in Osaka, with a national pavilion plus pavilions representing the provinces of British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec.

One big success at the Montreal Expo in 1967 had been a fast food outlet called Bobo Hut. Its boss, Graham Tilley, tried to transplant its bobo balls (spheres of ground beef, pork and chicken) to Japan without the benefit of market research and was puzzled by the incredulous reactions by some Japanese visitors, particularly those from parts of Kyushu and Kansai, some cackling gleefully. In certain Japanese dialects, it seems, bobo refers to the female reproductive organ.

Graham's bobos, dipped in a tangy sauce, were actually quite tasty. But while Japanese Expo visitors proved receptive to newfangled ideas like sushi served atop conveyor belts, unfortunately for Graham they weren't ready for a Canadian snack with a such a suggestive name.

New technology was also in force at Expo. In the central plaza at the International Bazaar was a huge "atomic clock" with digital readout built by Seiko, which claimed accuracy of plus/minus 1 second for over 1,000 years.

Naturally, Murphy's Law kicked in and the clock malfunctioned. Instead of chiming at the top of every hour, it began sounding off every minute on the minute. Its constant chiming threatened to drive us crazy, until Seiko's engineers remedied the flaw several days later.

Our Thai shop boasted a favorable location, facing the plaza and adjacent to shops representing Bulgaria and South Korea. Once, on a slow business day, Ivan, the Bulgarian shop's assistant manager, challenged our boss Peter to a Warsaw Pact vs NATO competition at a shooting gallery in neighboring Expoland. Although short in stature and stick-thin, Ivan proved to be a crack shot with a pellet gun, soundly defeating Peter and smugly walking away with an armload of toy prizes.

The South Koreans next door were initially livid. How dare the Expo organizers locate them next to a communist country! The first several weeks were tense, but emotions gradually subsided and a sort of symbiosis developed. When the Bulgarians needed to recruit Japanese-speaking sales clerks for their store, it was Mr. Kim, the Korean shop manager, who tapped into Osaka's large zainichi Korean community to introduce several charming young women to serve the customers in their shop.

The day Expo closed, on September 13, I admit to feeling a lump in my throat watching former adversaries Ivan and Kim exchanging gifts and embracing, while tearfully bidding each other farewell. That, in a microcosm, truly epitomized Expo 70's ambitious theme: "Progress and Harmony for All Mankind".

Setting down roots

Most of the foreigners working at the Expo departed Japan soon afterwards, but a few stayed on. Maureen Sugai – originally from Calgary – married a Dentsu ad executive and opened her own travel business in Osaka.

My former ICU classmate Mark "Rusty" Lavelle worked for an English school in Tokyo in the 1970s, and after operating a travel agency in California returned to Japan to work as a job recruiter. He passed away in 2015.

Perhaps the best known of the American pavilion guides to set down roots in Japan and go on to achieve fame and fortune was Marty Kuehnert.

A native of Southern California, Marty first arrived in Japan in 1965 to attend Keio University on an exchange program with Stanford University. After working at the Expo, he went on to become a sports consultant, restaurateur, newspaper columnist, author, TV broadcaster and university professor, among other roles.

Among Marty's long list of firsts in Japan, two in particular stand out: In 1977, while working for Osaka-based sportswear manufacturer Descente, he made headlines by convincing two U.S. major league teams, the Baltimore Orioles and the Pittsburgh Pirates, into procuring Japan-made baseball uniforms.

A year later Marty opened The Attic, Japan's first American-style sports bar, in Kobe, and it soon became the favored hangout by foreign players on the rosters of professional teams in the Kansai area.

After the January 1995 earthquake devastated Kobe, Marty relocated to Tokyo and would later fall in love with Sendai. He served briefly as general manager for the newly franchised Tohoku Rakuten Golden Eagles baseball team and went on to teach sports business at several universities, as well as serve as a senior advisor to the Sendai 89ers in Japan's pro basketball league.

Marty passed away in a Sendai hospital last November at age 78 following complications from heart surgery. Hundreds of friends and colleagues turned out for his memorial service on December 1. He was laid to rest in the Foreigners Cemetery in Kobe's Kita Ward, beside a son and infant daughter who predeceased him.

Mark Schreiber met his wife-to-be at the 1970 Expo and says one Expo is enough. He has no plans to visit this year's event in Osaka.