Issue:

June 2025

Infinity Books is an oasis of literature, music and camaraderie ... and things that go bump in the night

With fires devouring both ends of the Azumabashi Bridge, only a handful of people were able to cross Tokyo’s Sumida River. The writer Yoshie Funaki described showers of sparks falling on people standing on vessels beneath the span, their burning hair recalling images of the fire god Fudo.

Crowds had been trying to reach the eastern side of the river, where a twenty-acre open expanse of ground around the Honjo Army Clothing Depot offered the prospect of refuge from the M7.9 earthquake that had struck Tokyo just before noon on September 1, 1923.

Their clothes, luggage, and items of furniture would make the perfect kindle for the weirdest of phenomenon, as conflagrations from the two sides of the river, driven by prevailing winds, fused, forming intensely hot vacuums, a fire tornado that incinerated everything in its path. The ashes from the bodies of the estimated 44,000 people who perished at the depot would be hastily interred in crude receptacles made from corrugated iron.

If residents of the ill-fated, working-class district of Honjo thought the worst was over, they were wrong. On the night of March 9, 1945, US B-29 Super fortress bombers, their pilots no longer squeamish about eviscerating densely civilian populated areas, dropped a new type of incendiary substance. Asakusa and areas to the east, with their narrow alleys and flammable roofs, extracted the highest death tolls from the ordnance – a mix of jellied gasoline and magnesium known as napalm. Somewhere between 80,000 and 100,000 civilians died that night alone. It was America’s first high-tech massacre. The architect of this carnage, the cigar-chomping General Curtis May, would later confess that, had the U.S. been defeated, he would probably have been tried as a war criminal for the deaths of civilians that, in his own words, he had “scorched, boiled, and baked to death,” with impunity.

Crossing the Azumabashi Bridge today, leaving behind droves of Japanese and foreign tourists visiting the sightseeing spots of Asakusa, the devastation is of more recent making. Exiting onto the Honjo side of the bridge, I’m scanning the area for signs of the past. I’m hard pressed to find any structures dating from before the 1970s in a district that, deprived of sightseers, startup companies, or chic new tower mansions, retains a persistent pallor of neglect, one that quickly turns new buildings into shabby, non-descript structures. There are plenty of passing cars, but the streets are almost deserted of pedestrians. Real estate and rental fees in the district are predictably low. This I learn from Nick Ward, owner of Infinity Books, the store I’ve come to visit.

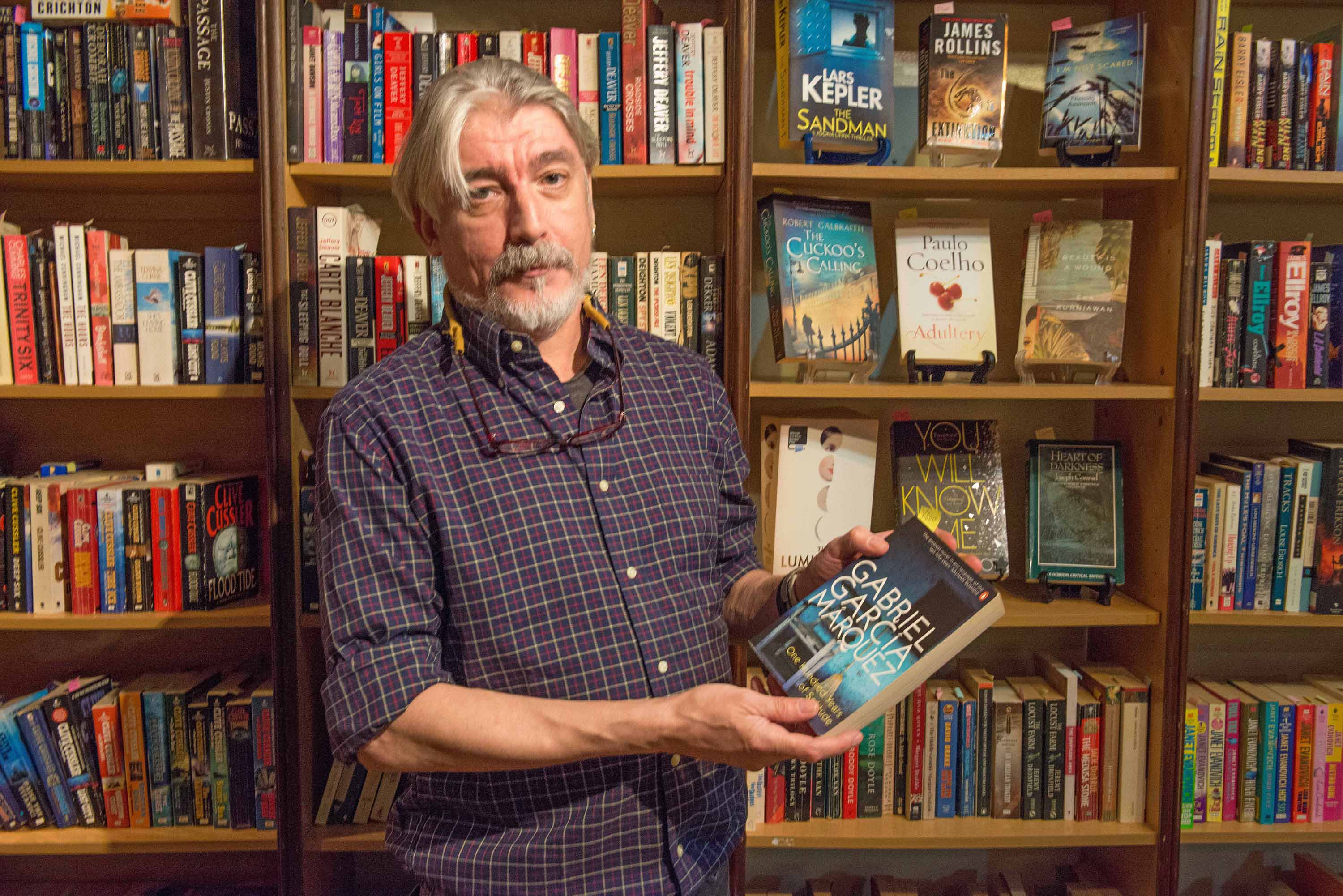

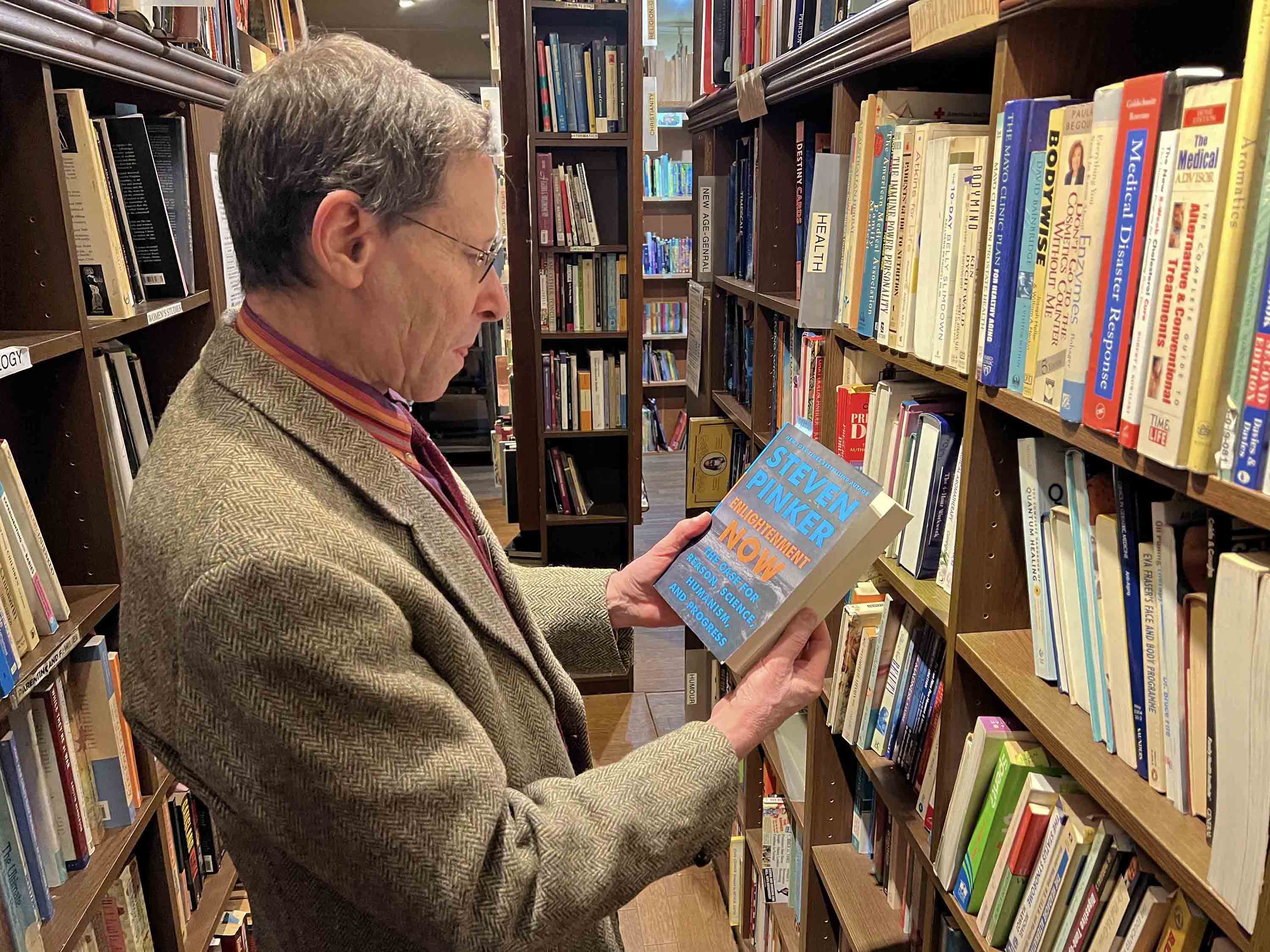

The shop is only 11 years old, but its seasoned wood interior, dim corners, and the faintly winey, yeasty smell of used books evoke an older ambience and habits that predate the age of tablet readers. It was designed and built by John Coyle, an amateur carpenter with professional skills. Ward had asked his friend: “If I find a blank space, can you help?” Aside from creating wood-paneled ceilings, walls, and a forest of book shelves a bar was added so that evening customers could enjoy a glass of beer or wine. The bar connection is no coincidence. Ward and Coyle once ran The Fiddler, a British pub in Tokyo’s Takadanobaba district. Coyle went on to oversee What the Dickens, a popular drinking spot in the more upmarket area of Ebisu.

Catering to just about every taste imaginable, the store stocks around 15,000 books. Given the volume of titles, the shop interior, a model of accessibility and fluid movement around its canyons of shelves, is a marvel of space management. Like some of the Bordeaux vintners I met when I lived in France – dedicated men who, literally, slept over their vats at crucial fermentation periods – Ward, protective of his stock and with an eye to cost cutting, used to sleep over in the shop. It was during those nights alone in the store that he first glimpsed ghostly presences floating in the air.

Manifestations of the restless spirits of the war dead that, putatively, still inhabit this area, Ward, though unruffled by the phenomena, asserting that they are harmless, non-malicious, no longer sleeps in the store. Claiming not to believe in poltergeists or apparitions, but to be simply witness to strange hauntings, shapes and light, whose forms and mobility happen to be otherworldly, he does recall books frequently falling off their shelves. He is not superstitious, but stands by what he has seen with his own eyes.

Like the more fortunate wartime residents of the district who lived through the bombings and emerged from the rubble intact, Ward is a survivor, though of a different kind. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the store remained doggedly open for business, welcoming a trickle of customers and running an online ordering service. As a struggling, small-scale business operator, Ward was eligible for economic assistance, but refused it. “I didn’t want any handouts from the government, so I turned instead to cloud funding,” he explains. Doing things his own way, finding solutions to existential obstacles, you might say, is Ward’s trademark.

Things have been looking up since the dark and dreadful days of Covid. A growing trickle of books are sold to customers abroad, and the store has started to sell a small, selective number of new titles. The recent influx of foreign tourists has provided an unexpected, and very different, shot in the arm. Easily located on Google, and within minutes of hotel-dense Asakusa, fiction, especially by Japanese authors such as Haruki Murakami, are popular among this newer clientele. There is also a strong interest in the work of best-selling Japanese women writers, such as Mieko Kawakami. Its only recently that Ward has started accepting credit card payments, another influence of foreign tourist custom.

The store hosts a lively events calendar, including heaps of music.

Many gifted musicians, both scheduled and spontaneous, perform in the store.

On a Saturday night, things can get wild.

Photo by Stephen Mansfield

He is an experienced publican with a license to sell alcohol, and the bar at Infinity Books has been instrumental, along with a lively calendar of monthly events, in keeping the business afloat. Hosting art parties, standup comedy shows, quiz and board game evenings, its Saturday night acoustic open sessions, highlighting an array of gifted musicians, are among its most popular events. I’ve attended a few myself, and can attest to the good vibes that music, one of the best forms of therapy we have, provides, especially when heard in the company of a friendly, well-lubricated audience.

It’s debatable whether every bookstore should have resident spirits, or eerie, floating filaments of ectoplasm, but most would agree that pets fit in very nicely. I’ve seen dogs, parrots, even a rather academic looking rabbit, in bookstores around the world, but cats do seem a natural match for such surroundings. Last month, while visiting the wonderful Garden Books in Shanghai’s old French Concession quarter, I spotted a beautiful tawny colored tabby cat, perfectly at home among the shelves of English titles.

Infinity Books has its own resident feline, named Oscar, after the ill-fated Irish playwright. A retiring shelter cat, usually found behind the counter, well away from customers, he is said to roam the empty store at night. Perhaps, the last word on mascot pets should go to Ward: “Every bookshop,” he insists, “should have a cat.”

Stephen Mansfield is a Japan-based writer and photographer whose work has appeared in more than 60 magazines, newspapers and journals worldwide. He is the author of 20 books.