Issue:

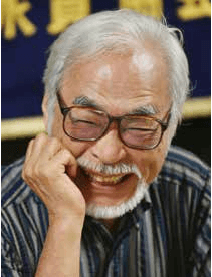

FCCJ journalists made the trek to the Tokyo lair of Hayao Miyazaki for an exclusive press conference.

by DAVID MCNEILL

GENIUS RECLUSE, ÜBER-PERFECTIONIST, lapsed Marxist, Luddite; like the legendary directors of Hollywood’s Golden Age, Hayao Miyazaki’s intimidating reputation is almost as famous as his movies. And for a long time Japan’s undisputed animation king was known for shunning the media. So it was a surprise when he agreed to an exclusive press conference with FCCJ journalists.

There were, however, some reliably eccentric catches. Miyazaki would not come to us – we would have to go to him in his leafy lair in Western Tokyo. The director dislikes the center of the city and rarely travels there, said his handlers at Studio Ghibli. He was also averse to electronic gadgets, iPhones, strong lights and microphones, along with journalists with the major Japanese media.

photo by KASAHARA KATSUMI

Miyazaki broke millions of hearts last year when he announced his retirement, though the 74 year old workaholic still goes to the studio every day. “All that’s changed is that I come in 30 minutes earlier and go home 30 minutes later than I used to,” he said. Ghibli still churns out short films, but Miyazaki no longer puts the studio on the line with the expensive, extraordinarily labor intensive features that won him global fame.

Many of Miyazaki’s movies are paeans to the natural world and coded warnings about its perilous state. He admits to hating most contemporary popular culture, particularly from the United States. His final film, The Wind Rises, is widely regarded to have also made explicit his long time antiwar politics and his concern that Japan is drifting from its post war pacifism.

Before its release, he declared his support for Japan’s war renouncing Constitution, saying he was “disgusted” by plans to change it. At a time when revisionist voices on the war seem to be in the ascendant, and liberal voices falling silent, he is also sharply critical of the behavior of the Japanese Imperial Army, saying he felt “hatred against Japan” when he learned what it had done in China. “I am taken aback by the lack of knowledge among government and political party leaders on historical facts,” he said.

It’s not surprising, then, that Miyazaki began with Okinawa. It is home to a bitter dispute over the construction of a new offshore base that is part of American military plans to contain China. In May, he became the most high profile backer of the Henoko Fund, which aims to collect donations to stop the base from being built, and it was this new role that the director wanted to discuss. “I want to convey to as many people as I can the reality of what is happening on Okinawa today that most people there do not want those bases,” he said.

MIYAZAKI WAS INITIALLY RELUCTANT to be a figurehead for the Henoko struggle but relented when he considered the years of injustice suffered by Okinawans. “I feel there are no apologies in the world that would make up for it, so I thought the least I could do was this.” As for China, its rise is “Japan’s greatest political challenge,” he said. But trying to contain it with military force was “impossible.” “It is that understanding that such things are impossible that led to the creation of our pacifist Constitution.”

Miyazaki was critical of the culture of waste and consumerism in Japan and contemptuous of plans to restart the nation’s reactors this year. “We are a land of volcanoes and earthquakes. Of course we should scrap our nuclear plants.” He laid the blame for many of Japan’s problems with the current crop of what he called “low level” politicians. “They now have nothing to hold them back so their true colors are showing. It’s sad to have to say that.”

The director reserved his strongest invective for the government of Shinzo Abe, which was trying to bulldoze a clutch of security bills through parliament as he spoke (the bills have since passed the lower house and will likely be passed into law in September). Miyazaki called that attempt “foolish” and took aim at the prime minister himself. “He probably wants to leave his name in history as a great man who changed the interpretation of Japan’s Constitution. But it’s despicable.”

He said he had little expectation in Abe’s upcoming statement on the 70th anniversary of World War II but offered his advice anyway. “He should include a very clear admission that Japan inflicted great suffering on China. There is a lot of political horse trading going on over the wording of the statement but I think it should be above politics. It should be a simple expression of remorse for the terrible things that Japan did in the past. I know many want to forget but it cannot be forgotten.”

Despite his sometimes pessimistic diagnosis of contemporary Japan, Miyazaki sounded an upbeat note on the future. “We are a people that live on a small island on the far reaches of a corner of the Earth. I believe we do possess the wisdom to live in our corner of the world in peace.” He said the failure of the Democratic Party (DPJ) liberal project, and the decisions to backtrack on Okinawa and hike the consumption tax had left many Japanese feeling “despair, hopelessness and distrust.”

“But that won’t last forever.”

David McNeill writes for the Independent, the Economist, the Chronicle of Higher Education and other publications. He has been based in Tokyo since 2000.