Issue:

August 2024

As Koshien stadium marks its centenary, another crop of high school baseball players dare to dream

Decades ago I attended the opening ceremony of Japan’s premier sports tournament, where teams marched into the stadium like their Taisho Era predecessors, then solemnly pledged allegiance to fair play before a baseball was dropped from a low-flying biplane to mark the start of the games.

Koshien's song, The Laurels of Victory Shine on You, played as the temperatures exceeded 30C. The ivy-covered stadium, nestled between Kobe and Osaka, produced non-stop sweat from teams and fans in the holiday drama, while the rare display of regional rivalry captivated with its earnestness and level of competition.

But I wasn’t alone in my fascination. The rest of Japan also tunes in from morning to closing siren on NHK to witness the battle of prefectural high school champions, while more than 800,000 people attend in person. They enjoy the summer diversion from the drudgery of everyday life, an opportunity for people from rural areas to take pride in their roots, depending, of course, on how their team performs.

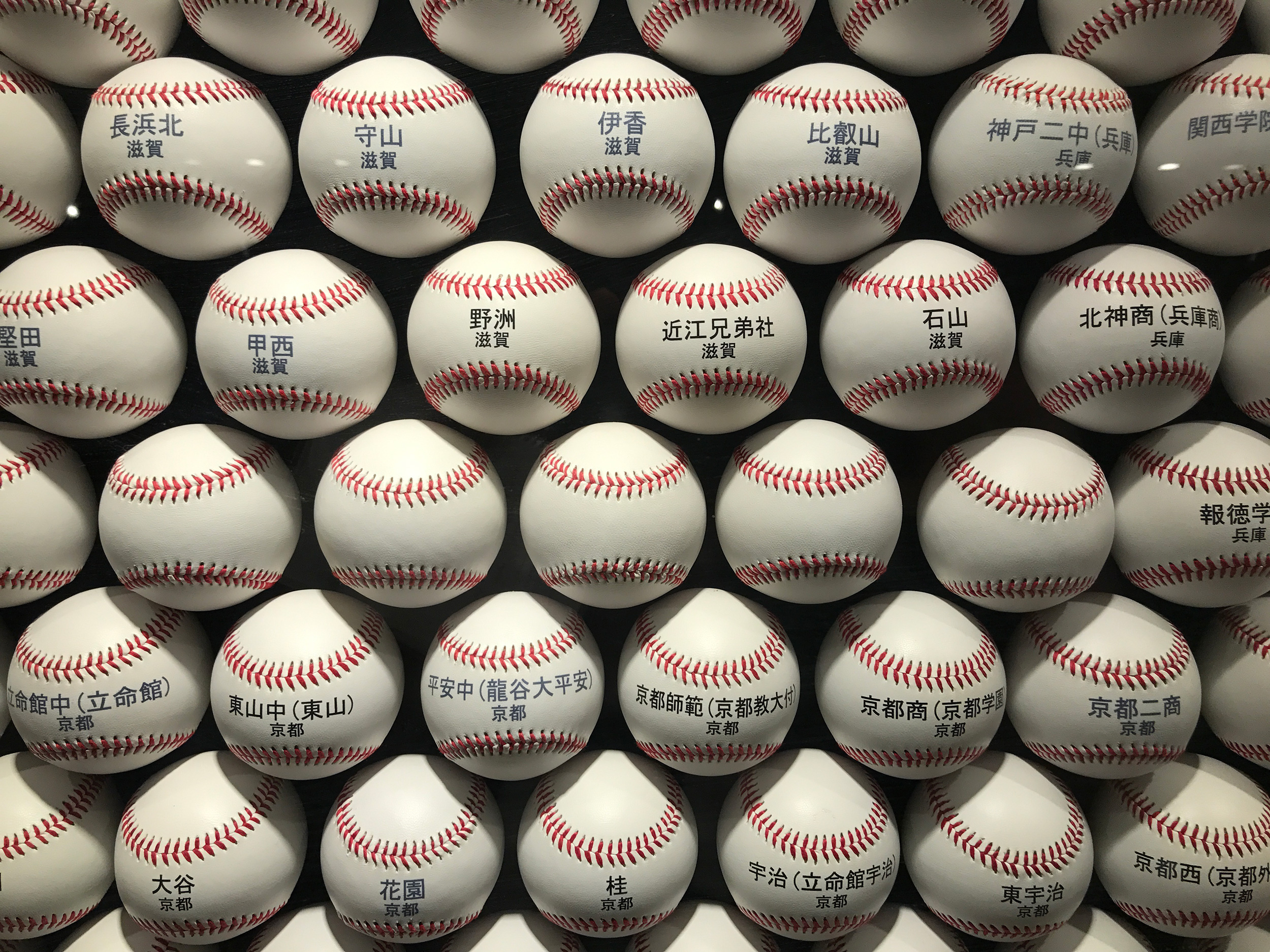

Koshien is the byproduct of Japan’s 47 prefectural tournaments, involving some 4,000 high schools. Just one game at the tournament can be life-changing for players, their families and supporters – an August of madness that lasts until the final team fights off tears and scoops infield dirt into bags as eternal proof that they played at the famous old ballpark.

Players from the first Okinawan team, Shuri Senior High School, collected soil in 1958 but were prevented from taking it home because the prefecture was still under U.S. control. Decades later, when the tournament was canceled due to the Covid-19 pandemic, players denied their opportunity to shine were sent keychains containing infield dust as compensation for losing their place on Koshien’s stage.

Koshien is often a springboard to Japanese Professional Baseball (NPB) or Major League Baseball (MLB), as the tournament is a televised stage for skills and endurance. Among the many success stories is Seiryo Senior High’s Hideki Matsui - nicknamed “Godzilla” – who was in demand for his batting prowess. Daisuke Matsuzaka, who tossed 881 pitches for Yokohama Senior High, including a no-hitter in the title game, was similarly coveted by pro teams on the strength of his Koshien appearance. And who could forget Shohei Ohtani, who at the age of 18 threw 160 kph pitches for Hanamaki Senior High, which failed to win the title but won over an entire nation.

Ohtani and fellow Hanamaki alumni Yusei Kikuchi appear in Koshien: Japan’s Field of Dreams, a 2019 documentary by Ema Ryan Yamazaki.

“High school baseball is this fuel, and especially in summer, you can’t avoid it,” said Yamazaki, whose film was recently screened in Tokyo. “At the sacrifice of some Japanese boys, it fuels the economy and spirit.”

“It’s like our World Series,” Ohtani says in the film, which depicts his manager, Hiroshi Sasaki, as a source of change. The film was shot during the tournament’s 100th edition in 2018, and details the struggle between its past and future, as well as the baseball dreams that, for most players, have to wait for another day to be realized.

But is there life after Koshien for those Boys of Summer who don’t turn professional?

“For a lot of kids in high school baseball, that’s the last time they’ll ever play,” Yamazaki said. “However, they leave not just knowing how to play, but also have a work ethic, team and collaborative skills that many Japanese companies look for.”

Players are expected to follow orders and make sacrifices, and Koshien’s military subtext is palpable. Early tournaments included Korean, Taiwanese, and Manchurian teams, while games were suspended during World War II, when the stadium was commandeered by the Japanese Imperial Army.

In the tournament’s current iteration, globalization and modernization still take a backseat to ase to namida (sweat and tears) theater. Some innovations have been made, such as allowing players to sport longer hair rather than the military-style buzzcuts of the past, as evidenced by the unruly locks worn by players from Keio Senior High when it secured its first Koshien title in 107 years.

The team’s manager, Takahiko Moribayashi, told the Kyodo news agency that such freedoms marked a new dawn for Koshien. "Perhaps this was a victory that will lead to a new look for high school baseball,” he said.

Yamazaki believes Japanese baseball is trying to distill the best from its long history, adding that the manner of success often dictates how subsequent Koshien tournaments play out.

“The team that wins Koshien every year kind of sets the trend for what people think is good,” she said. “The team from Akita (Kanaashi Nogyo High), a public school, had like 15 kids on the team, and one pitcher threw almost 1,000 pitches. This was in 2018, over 20 years after Matsuzaka.”

Veteran sportswriter Jim Armstrong says Yu Darvish, who played at Koshien before plying his trade in the NPB and MLB, reflected a change in the type of players on display at Koshien. “In addition to the fact he was a standout pitcher for Tohoku High in Sendai, he was the son of an Iranian father and Japanese mother, which made this an appealing story,” Armstrong said. “Darvish really stood out.”

More recently, Darvish was outspoken in his criticism of Koshien for not limiting pitcher use and ignoring dangerously high summer temperatures.

When this summer’s tournament starts on August 7, Koshien’s organizers, the Japan High School Baseball Federation and the Asahi Shimbun, will begin games earlier in the day and could suspend play if conditions become too hot. In addition, rosters have been increased to allow more player substitutions.

Other recent innovations included using male flag and placard bearers at the opening ceremony, while last year a woman served as the fungo hitter during team infield practice.

Yet Koshien’s greatest attraction is arguably found in what hasn’t changed. Despite talk of greater freedom for players, those who push boundaries, such as indulging in celebratory gestures, can expect a reprimand.

Armstrong says the innocence of youth is also an eduring attraction. “It’s seen as a pure form of the game, with players giving it their all before being tainted by money,” he said.

Koshien teams are usually prefectural powerhouses that recruit, train, and empower baseball prodigies – countryside factories making summer fireworks for all of Japan to marvel at.

In the final of my first Koshien, Tenri Senior High, representing Nara Prefecture, defeated Ehime’s Matsuyama Shogyo Senior High. They were both regular participants, although I have to confess I knew little about them. That summer, and during many since, all but one team and their fans have gone home defeated, but only the most distraught walk off considering themselves losers.

Instead, they look at the night sky, the school bus and their bag of dirt, and give thanks for their fleeting, glorious moment at the hallowed stadium that makes high school baseball shine.

Dan Sloan is a former president of the FCCJ, author, journalist, communications specialist, and - purportedly - the infamous left-fielder who threw the ball over the home plate backstop. He managed the Press Club Alleycats to two titles, and still plays for a remnant of the team.