Issue:

August 2024

The Teigin Incident remains one of Japan's most shocking crimes of the 20th century

In late spring of 1999, I was contacted by Burritt Sabin, editor of the now defunct the East magazine, who told me he was organizing a series of articles covering major events of the 20th century. Sabin knew about Crime and Punishment in Old Japan, which I was serializing in the Mainichi Daily News, and proposed I contribute an article about Japan's "crime of the century," whatever that may be. He suggested something about the Aum Supreme Truth cult that had released toxic nerve gas on the Tokyo subway four years earlier.

Considering the sheer scope of Aum’s nefarious activities and large number of victims, an article about the doomsday cult's depravities might have fit the bill. But instead, I proposed a topic that Japanese in an earlier age would probably have found even more shocking. After all, the very notion of an attempt on the life of Emperor Meiji – who according to Chapter I Article 3 of the Constitution of 1889 was "sacred and inviolable" – seemed unthinkable, more of a deicide than a regicide. We agreed I would do a story about the Great Treason Incident of 1910, still studied today as a major event in its time.

My first stop was Yochomachi, Shinjuku Ward, where a stone monument stands in a corner of a children's playground. Erected in 1964 by the Japan Bar Association, it marks the location of the gallows in the former Ichigaya prison. The inscription reads keishisha Ireito (tower for consoling the spirits of those punished by death).

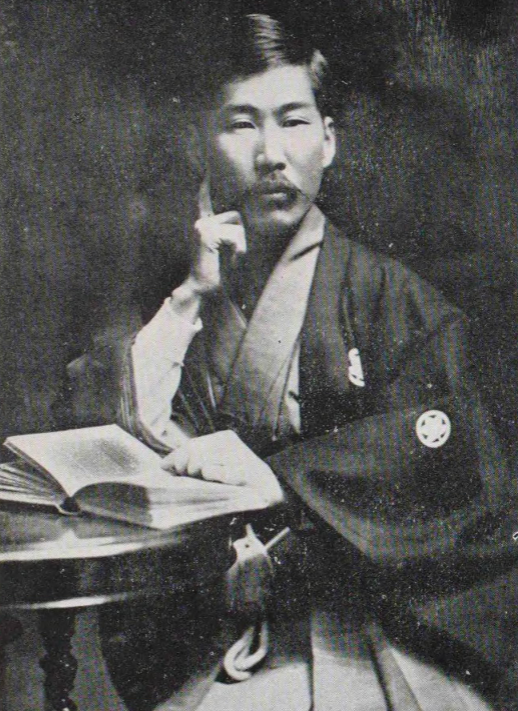

It was here that on January 24, 1911, 39-year-old Denjiro Kotoku, aka Shusui Kotoku, and 10 other alleged conspirators were hanged over their plot to kill the Meiji Emperor. Kotoku's former mistress, Kanno Sugako, the only woman convicted, went to the gallows the following day.

Kotoku had been a crusading journalist, political activist and publisher of the progressive Heimin Shimbun. His literary nom de plume Shusui, written with the kanji for "autumn water," figuratively means a well-sharpened sword.

A native of Tosa Province, modern-day Kochi Prefecture, Kotoku personified his home province's characteristic of tenacious, independent thinking. After being banished from Tokyo along with hundreds of other radicals in 1887 at the age of 16, he moved to Osaka and became a disciple of Chomin Nakae (1847-1901), a French translator who actively propagated Western liberalism.

From the 1890s, Kotoku had espoused increasingly radical politics. Writing for the liberal Yorozu Choho newspaper, he agitated against the notorious Ashio copper mine in Tochigi, whose toxic runoff wreaked economic hardship on farmers in the northern Kanto region. He also exposed acts of looting by high-ranking Japanese military officers in the wake of China’s Boxer Rebellion. Breaking off to establish his own newspaper, the Heimin Shimbun, he agitated against Japan’s involvement in the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-1905, which earned him a five-month prison term.

After his release in 1906, Kotoku traveled to San Francisco, where he spent half a year exchanging ideas with radical thinkers of all persuasions. He returned home a full-blown anarchist, and along with his ideological cronies found himself under heavy police surveillance.

On May 17, 1910, police in Matsumoto City, Nagano Prefecture, acting on a tip, raided the workplace of a man named Taikichi Miyashita and discovered bomb-making materials. Under torture, Miyashita admitted to a plot to assassinate the emperor.

A nationwide sweep of radicals ensued. Kotoku was not directly implicated, but was regarded as the radicals' ideological leader, and on May 28, was arrested and charged with high treason.

In a closed trial by the supreme court, which did not allow witnesses for the defense and whose ruling was final and could not be appealed, a total of 26 radicals, including three Buddhist priests, were found guilty of conspiring to assassinate Emperor Meiji. Twenty-four were sentenced to death by hanging, but 12 had their sentences commuted to life imprisonment. Two were convicted of lesser charges. The executions were carried out with extraordinary haste, only five days after sentencing.

It is generally believed today that Kotoku's role in the conspiracy was minimal at best – he was essentially convicted of guilt by association.

In 2002 I visited Kotoku's birthplace in Nakamura (renamed Shimanto City since redistricting in 2005), Kochi Prefecture. A city of about 40,000, its public library maintains a small museum displaying Kotoku's desk, bookshelves, published works, calligraphy and other memorabilia.

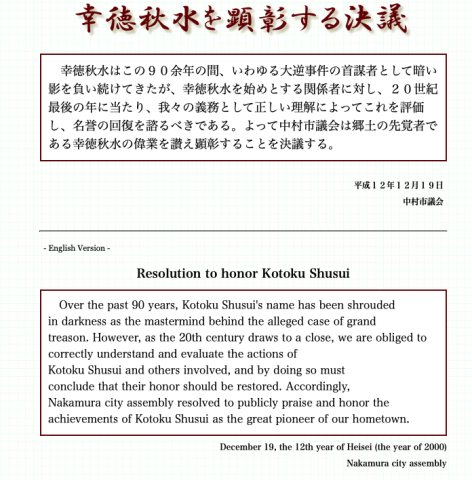

Kotoku is buried at the Shofuku-ji temple, where on January 24, 2002, I joined several dozen townspeople at his grave to commemorate the 91st anniversary of his death. In December 2000, Nakamura's city assembly had voted to exonerate Kotoku for his alleged crimes and "publicly praise and honor" his achievements. A local support group with over 300 members meets for study sessions on the second Sunday of each month.

My alternate choice for the most memorable crime of the 20th century was one that gained an arrest and conviction, but to this day has never been satisfactorily resolved. It took place on the afternoon of January 26, 1948, when a man identifying himself as Dr. Jiro Yamaguchi of the Ministry of Health and Welfare knocked at the side door of the Teikoku (Imperial) Bank branch at Shiinamachi, Toshima Ward.

The bank had just closed for the day. The man summoned assistant manager Takejiro Yoshida and explained that an outbreak of dysentery had occurred, caused by water from the neighborhood well. As one of the persons stricken had been in the bank earlier that day, Yamaguchi had been assigned to treat all those who might have been exposed.

He opened a small metal case, from which he extracted two bottles, labeled First Drug and Second Drug in English.

As the 16 people gathered around him, the medicine was apportioned into their teacups.

The drug he was about to give them, he explained, was very effective, but so strong it was capable of damaging their teeth enamel. It was therefore essential it be ingested straight down. After waiting precisely one minute after swallowing the dosage, he told them, he would administer a second preparation. But, he stressed, they would have to wait one minute before taking it.

The 16 people downed the preparation in unison and then, grimacing at the drug's bitter aftertaste, waited with increasing discomfort as the doctor methodically prepared dosages from the second bottle. Soon they were writhing on the floor in agony. The "medication" turned out to be a powerful poison, and 10 of the 16 who took it were dead within minutes. Another two died later in hospital.

The perpetrator absconded with about ¥160,000 and a check for ¥17,000, inexplicably leaving behind a considerably larger amount, about ¥350,000, on the accounting table.

The four surviving witnesses would recall their assailant as being of short stature and medium build, in his late 40s or early 50s. He had short-cropped hair, a pale complexion and several dark discolorations on the right side of his face.

Investigators soon learned that the same man had apparently made practice runs at two other banks: the Yasuda Bank in Ebara, Shinagawa Ward, on October 14, 1947, and the Mitsubishi Bank's Nakai Branch in Shinjuku Ward on January 19, 1948. In the latter case he had also used the name Jiro Yamaguchi.

In a memorandum to GHQ dated June 26, 1948, the investigators stated that the criminal was likely to be a person with knowledge of public health who was trained as a doctor, dentist, pharmacist, or engaged in production or sales of chemicals; who had contacts with occupation forces; who was a repatriated Japanese or perhaps former serviceman, probably a medical corpsman or someone familiar with training in epidemic prevention in areas hit by floods.

Meanwhile, the police made contact with Shigeru Matsui, the doctor whose business card had been used at the Yasuda Bank the previous October. Matsui assisted the police in tracing the individuals with whom he had exchanged cards.

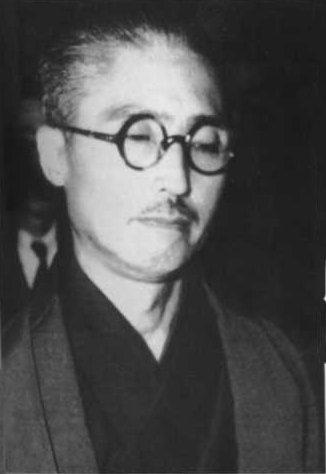

This eventually led police to Sadamichi Hirasawa, a 57-year-old tempera artist of some renown. Hirasawa readily admitted to detective Tamegoro Igii that he had exchanged cards with Dr. Matsui on a ferry to Hokkaido the previous summer, but insisted that he had lost the card when his pocket was picked.

When Igii visited Hirasawa in Otaru, he found Hirasawa unusually talkative about the Teikoku case. Igii wanted a take a photograph back with him to show to witnesses, but when they posed together, at the last second Hirasawa turned his face and thrust his jaw downward, as if trying to change his appearance.

Igii's suspicions hardened and Hirasawa was arrested in Otaru on August 21. Hirasawa's claimed alibi for the time of the crime was disregarded. Investigators also learned that he had come into a large sum of money whose source he could not, or would not, explain. After 62 interrogation sessions spanning 35 days, he confessed to the killings on September 27.

One explanation offered for Hirasawa’s sketchy memory and suspicious behavior is Korsakoff’s psychosis, a not-uncommon disorder also referred to as the amnestic-confabulatory syndrome.

After having been bitten by a rabid dog in 1925, Hirasawa underwent the painful series of inoculations to prevent rabies and was in a delirium for most of the next three months.

Among the characteristics of Korsakoff’s psychosis are impairment of recent memory and confabulation, i.e., the fabrication of ready answers or the recital of fictitious experiences. A person exhibiting such symptoms seldom gives the same story twice.

Based on the existing criminal code, Hirasawa was not allowed to recant his confession. Found guilty, he was sentenced to death by the Tokyo District Court on July 24, 1950. The sentence was confirmed by the Tokyo High Court in September 1951 and in April 1955 the Supreme Court rejected his appeal, setting the stage for his execution.

But doubts over his guilt lingered, to the extent that no minister of justice in subsequent years was willing to sign off on Hirasawa's execution. Hirasawa not only outlived Yoshio Yamada, the head of his first defense team, but his next two lawyers as well.

The enfeebled Hirasawa was transferred from death row at Sendai Prison to a prison hospital in Hachioji where, after battling pneumonia for over a month, he died at age 95, more than 39 years after his alleged crime.

A month before Hirasawa's death, Amnesty International appealed to the Japanese government for a commutation of his sentence, but to no avail.

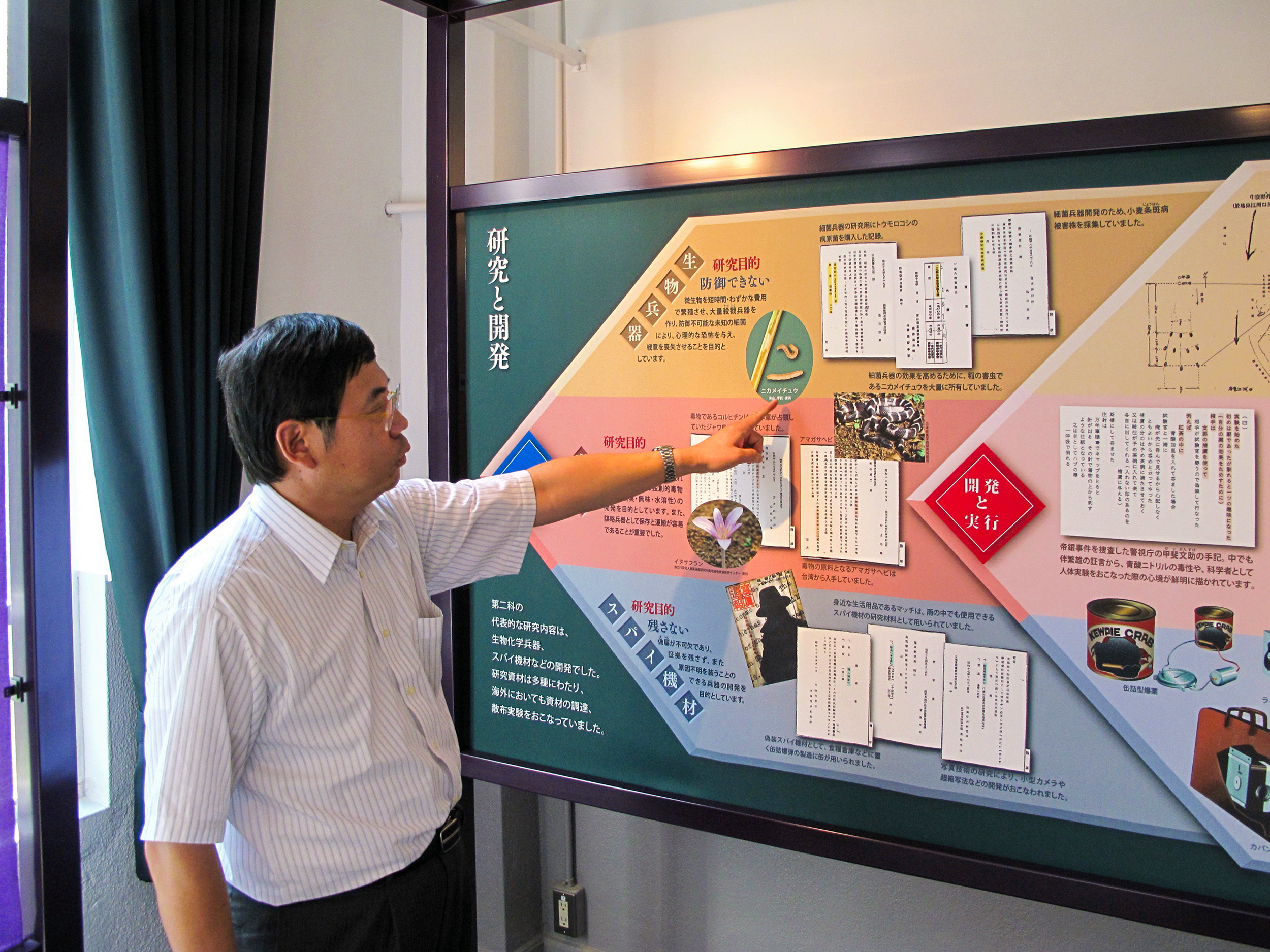

Nearly 77 years on, the enigmatic saga of the Teigin Incident has yet to be concluded. In recent years, it has been energetically researched by Akira Yamada, curator of the Noborito Peace Museum on the Ikuta campus of Meiji University. Yamada is convinced the poisoning technique used by the Teigin killer was developed at the Imperial Japanese Army's secret laboratory at Noborito, an affiliate of the notorious Unit 731 based in Pingfang, Manchukuo.

Among the various questions raised by Yamada were witnesses recalling a lack of mud on the culprit's boots, suggesting he had been driven to the bank in a military jeep – pointing to the possibility of GHQ involvement. Were the killings intended as a "demonstration" of the poisoning technique's effectiveness?

In a country where bank robberies were virtually nonexistent at the time, the Teigin Incident stands out as one of Japan's most enigmatic and convoluted crimes of the 20th century. It may be overly optimistic to expect that the real Teigin killer will ever be conclusively identified; but might Yamada's recent findings help to establish reasonable doubt? On Nov. 24, 2015, attorneys representing the lineal descendants of Hirasawa filed the 20th appeal for a retrial.

Mark Schreiber is author of Shocking Crimes of Postwar Japan (Yenbooks, 1996) and The Dark Side: Infamous Japanese Crimes and Criminals (Kodansha International, 2001).