Issue:

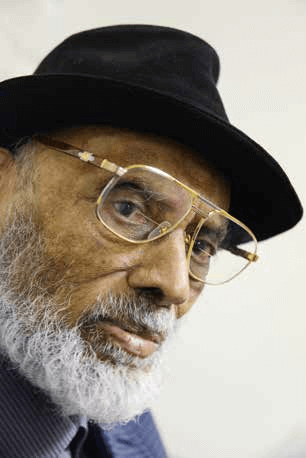

Vellayappa “Chuck” Chokalingam

by MONZURUL HUQ

OUR BELOVED CHUCK LINGAM breathed his last peacefully at home on Sept. 23. He had been hospitalized from a bout of pneumonia but had recovered and was released on Sept. 9. He would have been 101 years old this month.

Those who had become close to Chuck during his long tenure as a member of the FCCJ will all remember him fondly and feel his absence in their hearts. He departs us after travelling a long road stretching over a century that made him a living witness to events shaping modern Japan. Born in Nov. 1914, Vellayappa Chokalingam, known to fellow Club members as “Chuck” or “Lingam,” came to Japan in the 1930s and joined the Club half a century ago in 1965. As a result, remembering Chuck is like remembering the many years of the existence of the FCCJ, as well as Japan’s war time and post war history. In some ways, Lingam’s history mirrored Japan’s. A quick glimpse at the duration of his life, particularly the part that he had spent in Japan, provides us with convincing evidence in support of this presumption.

He was born to a South Indian merchant family with business interests in Malaya and Singapore. Many of the male family members of the well established clan had been sent to Europe for higher studies and Lingam, too, was offered that opportunity. Instead, after completing high school in Singapore he decided to travel in the opposite direction and sailed for Japan with the dream of becoming an engineer specializing in power generation. He hoped to eventually put into practice the knowledge acquired in Japan to expand the family business in the power sector. But destiny had something else in stock for him.

His first encounter with Japan was at the port city of Nagasaki on a sunny morning in the spring of 1935. The 21 year old Lingam had not the slightest hint that his stay in the country would be a long and eventful one full of exciting encounters at a turbulent time of Japanese history. That first encounter also exposed his youthful eyes to a few contradictions of Japanese life. As his ship approached Japan from Singapore, he was pretty sure that he was going to encounter a country preserving its oriental traditions, which he had seen being appreciated in other parts of Asia. People he met at Nagasaki, however, were all dressed in Western attire; he had an initial sense of relief, convinced that the dress code was a sign that Western languages were equally at home. To his surprise, nobody spoke a single word of English and he had to find the way to the station himself, with much difficulty.

In Tokyo he enrolled at Kogyo University and rented a place near Shinjuku. It was a time when exiled Indians in Japan were organizing a liberation movement that would free India from British colonial domination. After the beginning of the war, as the imperial Japanese army started moving westward from Burma, the movement received the patronage of the Japanese government. It was sometime during the period that the leader of the movement, Rash Behari Bose, asked young Lingam to become his private secretary. Though he was a bit hesitant at first, believing that accepting the offer might disrupt his study, he decided to join Bose and his close association with the leader continued until Bose’s death in early 1945.

Japan’s defeat placed Lingam in a difficult situation as he was essentially a part of the losing side. But he was eventually able to overcome that difficulty with the help of friends and acquaintances in Japan. The second phase of his life took him into the world of business where he eventually established himself as a successful Japanese businessman of Indian origin. India had always been close to him, but deep in heart he was much closer to his adopted country that he thought had given him so much. Joining the FCCJ in 1965, he gradually became a familiar figure who would spend much of his free time surrounded by his friends at the Club, which honored him with a life membership on his ninetieth birthday in 2004.

In an interview with No. 1 Shimbun last year, on reaching the milestone of 100 years, Chuck was asked how he felt being a centenarian. His quick reply was “nothing changes.” Yes, Chuck, nothing overtly changes as we pass our ordinary days and get on with the difficulties of life. But we also know that there are times when a vacuum appears somewhere deep inside, a void that nothing can fill up. This is exactly what many of us feel right now as we realize we will no longer share your presence.

Monzurul Huq represents the largest circulation Bangladeshi national daily, Prothom Alo. He was FCCJ president from 2009 to 2010.