Issue:

An expert in verifying content and social media newsgathering at the New York Times shares the advanced technology behind his work at the forefront of digital forensics

Malachy Browne is a senior story producer on the Visual Investigation team at the New York Times. A native of Ireland, Browne became an expert in social-media newsgathering and verifying user-generated content through his work at Storyful and Reported.ly. In 2016, he took these skills to the New York Times, where he has become a pioneer in the field of visual investigations, which mixes traditional reporting with digital forensics. This frequently involves recreating crime scenes by using 3D modeling, satellite imagery, and images filmed on cell phones.

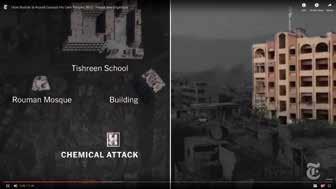

Browne has led a number of award winning investigations, including into journalist Jamal Khashoggi’s murder at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, chemical attacks in Syria, and the shooting of a young medic in Gaza.

Here are some of Browne’s current favorite tools:

SATELLITE IMAGERY

“We use satellite imagery in almost every story that we do. It can reveal details about when there’s changes to topography. Also, for example, if a building is hit in an airstrike, we can confirm that it happened within a 24-hour period.

“An example: Dataminr sent us an alert that there was an airstrike on a migrant detention center in Libya. We started getting reports on Twitter, and Libyan media had some accounts, but very few images. Then, we found a livestream on Facebook by one of the organizations that runs the center. And so, everybody’s worst fear that this actually did happen looked like it was legit.

In order to verify the exact location that was hit within the migrant detention center, we looked for old videos of that particular detention center, called Tajoura. We found an old video of the center’s opening ceremony on YouTube. So we could see that it was actually the exact same place that was blown to smithereens in the pictures that were coming out. Because the old archival video had so much panning across the migrant center, we were able to locate the exact building. Then we talked to a satellite imagery company and got fresh satellite images.

“We also analyzed and translated a couple of on camera videos with migrants who were there that were posted overnight. Some said, ‘We were working in the weapons depot, cleaning weapons as we usually do, and there was an airstrike on the weapons depot, and so we ran out and we were forced into the migrant lodgings, which is across the way.’ By tracking down some of those people, and by tracking down freelance journalists who had worked on the migrant issue, we then were able through WhatsApp to get in touch with witnesses.

“They sent us photographs of them working in the weapons depot. These migrants who are trapped in the center and not allowed to leave are also forced by the militia to work in the weapons storage area, which is a legitimate target in the middle of a civil war. And from the satellite imagery, we could see that the center was also bombed so the witnesses’ story was correct.

“We use a number of satellite imagery tools, like TerraServer or Planet Labs. They provide satellite imagery almost every day from almost everywhere, and you can search through the images. It’s not always very high definition, but sometimes it can be quite good. Maxar DigitalGlobe provides the highest resolution imagery. These platforms are not hugely expensive, so for a newsroom that is thinking of making better use of satellite imagery, it’s a nobrainer costwise.”

DRONES AND 3D MODELS

“We took an experimental approach last year in recreating a protest site in Gaza in 3D. The story we were investigating was the shooting death of a medic who was working there. It was a chaotic moment a bullet rang out and she died. Our question was: Can we accurately freeze that moment in time and space, and examine what was going on? Who was where? Where were the protesters? Where were the medics? Where were the soldiers? Why was that shot fired, and how did she get hit? Was she directly targeted?

“We went through our normal steps of collecting as much video evidence and photographic evidence from the day as possible. We collected 1,300 photos and videos from the original devices people used to film there, meaning we had all their metadata, and we could organize it.

“Then we went there, and using a high definition drone, filmed the entire area. Using a technique called photogrammetry, you can take that footage and create a 3D model of it. We used the photogrammetry software RealityCapture, and worked with the London based research agency Forensic Architecture to work on the 3D model in Blender, which is an open source program.

“Using the footage that we had from the day, we sketched in some of the details that the drone didn’t pick up. We placed the snipers, army jeeps, the fence, the coils of barbed wire before the fence. The model was so precise that we were able to slot in and calculate where the cameras were rolling at the time by looking at objects in the distance, like the fence or the tower or tufts of grass, and line up those cameras in the model.

“We could retrace the paths of the cameras, and freeze them at that critical moment when the shot rang out from six different angles. That allowed us to analyze everything, measure where people were, and ultimately ask the question: Was that gunshot justified? And was the violence such that there was an immediate threat to life at the other side of the boundary fence with Israel?

[The 3D model] allows us to get into really specific details about the moment that it happened. So when we interview the Israeli authorities about it, we have very specific details. We can match those details with what they say was going on at the time, and present the truth.”

SAM DESK

“One of the tools we use a lot for newsgathering or content gathering is SAM Desk. It’s a paid for tool that allows you to search for certain keywords across multiple social media platforms at once, and it allows you to filter for videos, pictures, and text. You can turn the results on and off, depending on what you’re looking for. Very often, we’re looking for video content. We might put in a place name or a hashtag or a very specific search term. It’s a bit like TweetDeck the results come in columns, so you can keep an eye on it.

“It’s also good for monitoring situations. If there’s a particular story that’s ongoing the Sudan protests or protests in Venezuela, for example you can keep checking it day in and day out. It also allows you, from those search results, to collect tweets or videos or whatever it is into little collections, in which you can do your work on them. You can set tags to say whether it’s verified or unverified and put in notes from your team. Depending on the platform, it will automatically archive the footage as well so if it’s later taken offline, it’s preserved.

“It also allows you to search for geolocated content. You can put a pin on ‘Hamburg,’ for example, and create a circle around it, or draw a map, and say ‘give me everything that’s geotagged from that area.’ And because its search results include snaps from Snapchat, which are almost all geolocated, that can be quite useful.”

EXIF DATA VIEWERS

“EXIF data is raw information, like the hour, minute, and second that a video or a photograph was taken. Sometimes, it contains GPS data as well, depending on the device. We’ll use an EXIF data viewer to extract that information, which can help with the verification process.

“EXIF data can be manipulated, so we never rely on one piece of evidence. It’s the same as traditional reporting: we’re always looking for corroborating pieces of information, asking who’s the second source, the third source, etc.

But EXIF data is quite useful, particularly when you want to reconstruct a timeline of an event to understand what happened when you weren’t there but a lot of footage exists. EXIF viewers are important in organizing all the evidence.

MONTAGE

“Montage is an advanced YouTube search. It allows you to search by date, and also by place if you want though not a lot of YouTube content is geotagged. But, a little bit like SAM Desk, it also allows you to collect videos into projects and to comment and put tags on them, and at specific moments in the videos as well. It allows you to organize YouTube content and zoom in on the details as a team. And that’s quite useful, especially if you’re doing historical investigations; so much content from the Arab Spring, for instance, is uploaded onto YouTube.

“It can also be useful just for finding archival reference material. For example, you might want to verify an airstrike location using Google Street View or satellite imagery on Google Earth. But sometimes, the street view isn’t available, or the satellite imagery isn’t good enough. However, if it’s a location that has been used often before, then there’s probably going to be YouTube videos of it out there."

InVID

“One last tip: Another tool we often use is the InVID Project’s Chrome extension, which is a one stop shop for getting YouTube video upload times, doing advanced Twitter search, doing reverse image search, doing video keyframe or thumbnail search, and finding metadata.”

Gaelle Faure is associate editor of the Global Investigative Journalism

Network (GIJN).