Issue:

March 2023

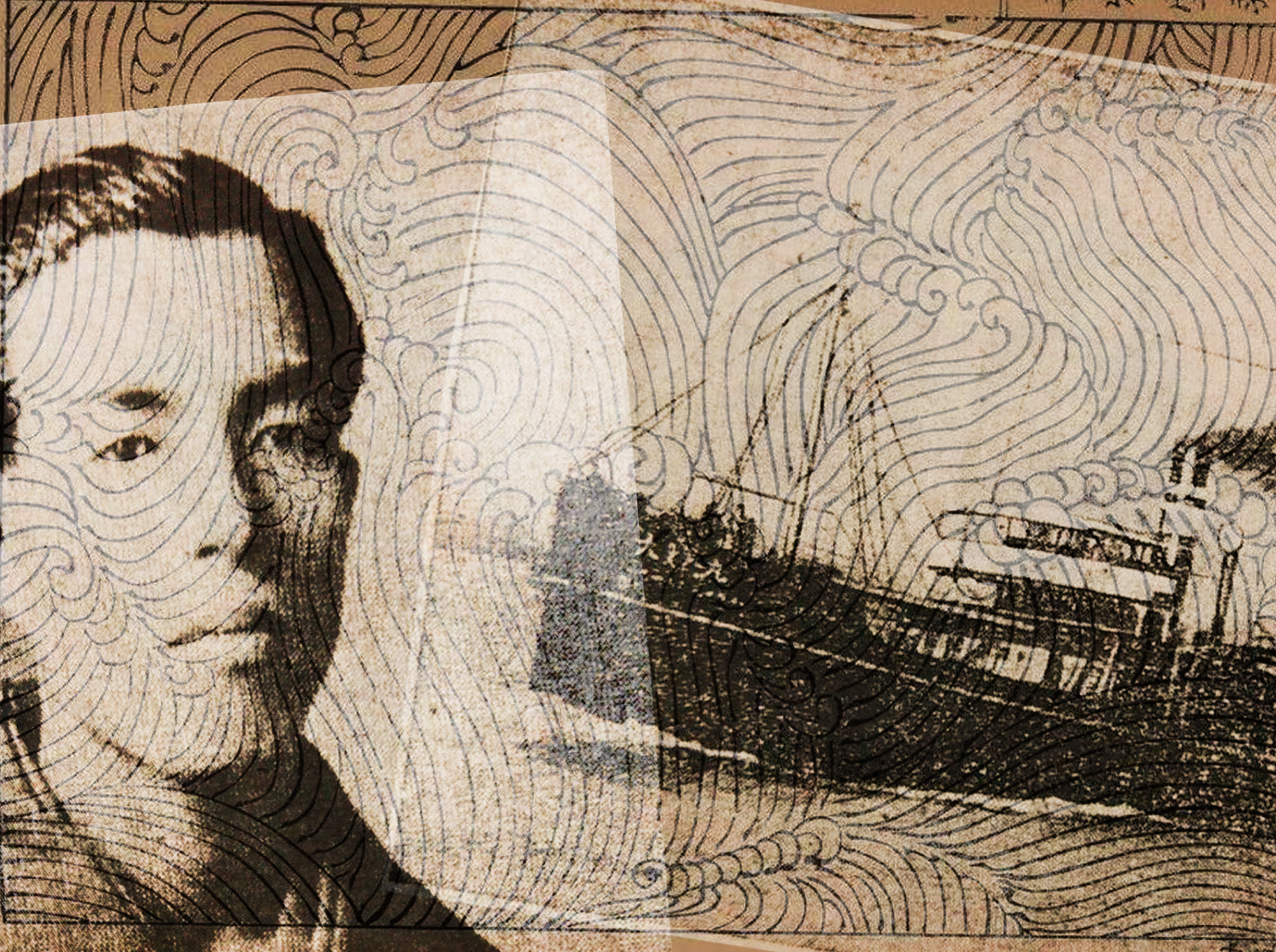

Riki'ichiro Ezure – the Japanese pirate who took on the Russians

Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-5 was followed in 1918 by the so-called “Siberian Intervention,” in which the armed forces of Japan and other allied countries occupied extensive parts of Siberia during the Russian revolution.

In 1920, a short-lived "Far Eastern Republic" was formed as a buffer state between Japan and the Soviet Union. But Bolshevik units continued to advance against White Russian forces under Admiral Kolchak, and this spelled doom for a community of some 700 Japanese civilians in Nikolayevsk, a port at the mouth of the Amur River.

On May 25, 1920, not long after the Japanese army unit defending the city had been ordered to withdraw, Japanese civilians were assaulted by communist partisans in an incident known as the Niko Jiken (Nikolayevsk Incident). The small remaining garrison of Japanese soldiers was wiped out to the last man and the port city's Japanese consulate burned to the ground.

Naturally, Japan was outraged. And one Japanese in particular, an avowed nationalist named Riki'ichiro Ezure, took it so personally he went out of his way to exact revenge.

The scion of a wealthy family, Ezure (1887-1954) had dropped out of Meiji University in his sophomore year, spending his college tuition funds to travel throughout Asia. He subsequently joined the army, while refining his skills at judo, kendo, and other traditional martial arts.

By April 1922, not long after his discharge from the military, the then-35-year-old Ezure made the acquaintance of a self-described former Russian officer named Serbunikov, who appealed for help in wresting the Russian Far East from the communists to establish an independent country friendly to Japan. As a step toward this goal, the two plotted to gain control of a gold mining region, said to be only lightly defended, and plunder its gold ore.

Ezure persuaded several Osaka trading companies to back his expedition. He recruited a crew of about 30 rough-and-tumble men, purchased a quantity of light arms and leased the Taiki Maru, a 644-ton steamer. On September 17 he sailed from Tokyo’s Takeshiba pier stocked with several months’ provisions.

Disregarding a cable from Japan's foreign ministry requesting civilian vessels to steer clear of Russian waters, Ezure sailed northward. Upon arrival in Japanese Sakhalin, he made contact with the commander of the local military garrison and took delivery of 100 infantry rifles and 10,000 rounds of ammunition.

On October 10, the Taiki Maru – its name masked with coal tar –arrived in Nikolayevsk. Observing the strength of communist forces in the region, Ezure promptly realized that Serbunikov’s scheme to grab control of the gold fields would be futile. But having come this far, he remained determined to engage in some mischief.

The Taiki Maru took on supplies and sailed from Nikolayevsk, pulling behind it a smaller ship, the Yukoku Maru, whose owner had requested a tow back to Japan. On the afternoon of October 13, Ezure spotted a small Russian steamer, the Anna. Signaling that he had run aground, Ezure requested a tow, promising to pay for assistance. When the Anna pulled up alongside, six Japanese crew members leaped on board, brandishing pistols and swords.

The Anna’s Russian crew members were quickly subdued and bound with rope, and its cargo was transferred to the Taiki Maru. A few days later, the Taiki Maru attacked a second Russian vessel, a masted schooner, shooting its officer and throwing several sailors overboard to certain death in the frigid Sea of Okhotsk. The remainder of the crew, consisting of six Russians, four Chinese and a Korean, were hogtied and the ship’s cargo, mostly salted salmon, was confiscated.

On the night of October 25, Ezure decided to dispose of the prisoners. Beginning with the ship's captain, they were led out on the deck one by one. Ignoring pleas for mercy, the Japanese crew shot them, fastened weights to the corpses and flung them overboard, after which they scuttled the Russian ship. Two days later, four surviving crew members of the Anna were summarily executed with Japanese swords.

After the murder over two dozen innocent civilians, the Taiki Maru “triumphantly” steamed to Otaru port on November 6, where its crew disbanded. After selling off about ¥70,000 (equivalent to around ¥114 million today) worth of loot, ¥60,000 (about ¥98 million) went to the costs of leasing the Taiki Maru and other expenditures. The individual crew members each received only ¥150 (approx. ¥240,000) for their efforts.

Ezure’s murderous exploits might have remained undiscovered if not for a crew member named Mikizo Tanaka. Feeling pangs of conscience, Tanaka went to the Tokyo police in November and blurted out a full confession, upon which Ezure and 33 others were arrested and charged with armed robbery and murder. On February 27, 1925, the Tokyo District Court found all 34 guilty. Ezure and two others were sentenced to terms of 12 years, with the rest of the crew receiving shorter sentences.

While in prison, Ezure wrote an instructional book about shinkaito-ryu stick fighting techniques.

Meanwhile, the tenuous years of Taisho Democracy soon gave way to the Showa Depression, and Japan became increasingly engrossed in nationalistic fervor. Ezure, previously described in the media as a “pirate gang leader” and “lawless terrorist,” came to be hailed as a “righteous samurai,” “nationalist” and “hot-blooded hero.”

Vowing to “tell the story like it really was,” Ikko Fujishima published a detailed account of the Taiki Maru incident in the December 1929 issue of Bungei Shunju magazine. The following year, popular author Otokichi Mikami published an article in Chuo Koron magazine titled Riki'ichiro Ezure, man of extraordinary talent.

Thanks to a special amnesty in 1933, Ezure was released early from prison, but was arrested the following year on suspicion of involvement in the Marie Lausanne gold salvage case. This time he was acquitted.

Ezure became involved in brokerage work and after the end of the Pacific War was in and out of trouble with the law. He was named as a person of interest in several fraud cases, including the 1947 Yamagata Agricultural Society concealed supplies fraud case, the Tokyo Metropolitan Bureau of Education case and the Oh Taisho case. He died in Tokyo on October 15, 1954 of unknown causes, at age 67.

Two members of the Taiki Maru's crew escaped indictment on the charges. One, captured after the Pacific War, was tried and convicted, but received a suspended sentence. The second remained at large. Finally, on February 28, 1967, 45 years after the incident, the Tokyo District Court ruled that the statute of limitations had expired and declared the case closed.

In 1976, writer Shozo Kosakai published Akai Fusetsu (Red Blizzard), a fictionalized account of the Taiki Maru incident. With Russia so frequently in the news since the start of its war with Ukraine, it was hardly surprising that the century-old story was retold in the September 4, 2022 issue of Shukan Bunshun's online edition.

Its author, Atarashi Koike, ended on this note: “Now, a century later, how calm would Japan's media be if, for example, a similar crisis were to occur on this country's boundaries? Might not the public be caught up in a whirlpool of enthusiasm, irrespective of the possible danger?”

A translator, columnist, author and avid book collector, Mark Schreiber has lived in Tokyo since 1966.