Issue:

March 2023 | Obituary - Pio d'Emilia

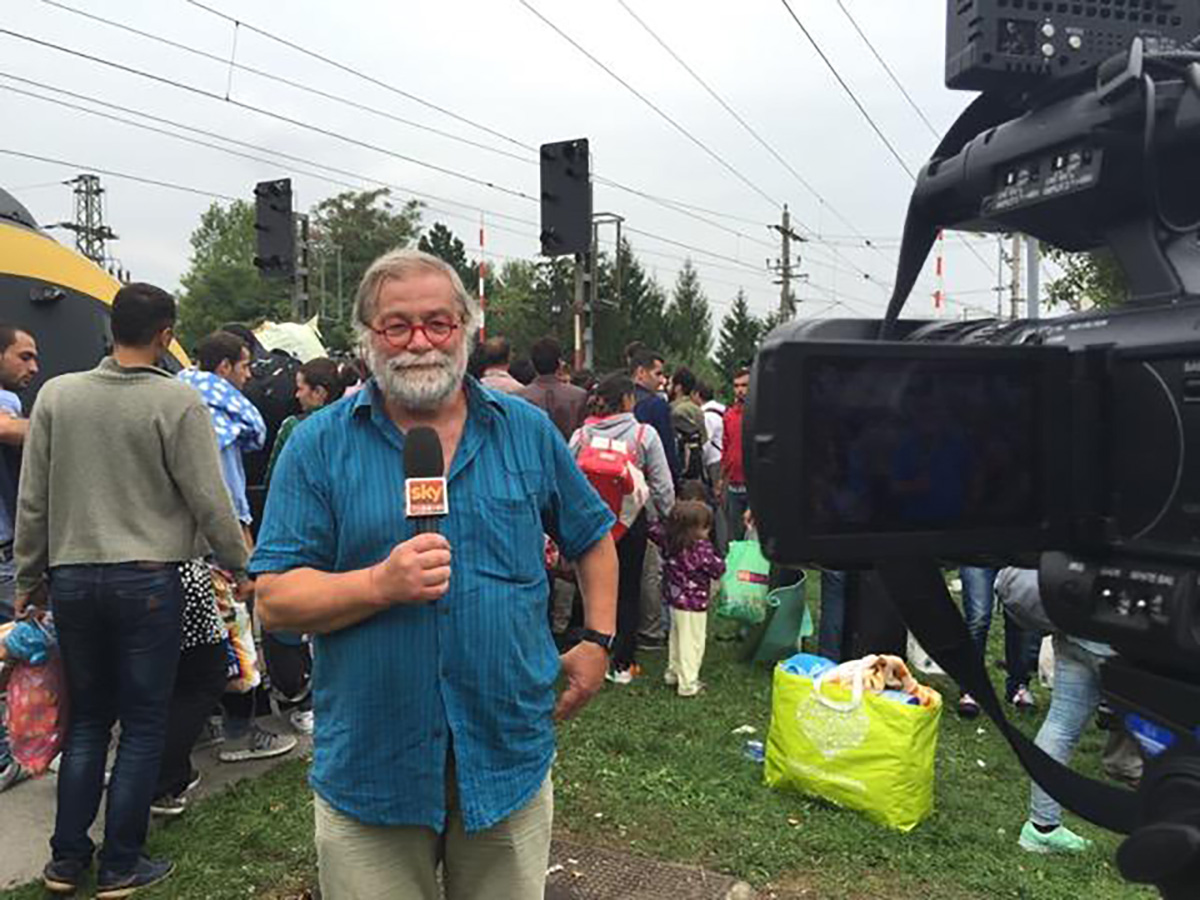

A vivid life, well lived. Remembering Pio d'Emilia

An unusually large afternoon crowd had gathered in the main bar of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan. It was election day, 2002. Pio d’Emilia was running for second vice president. His candidacy was controversial not only because of his leftist leanings, but because the club’s second vice president is in charge of personnel policy and there were concerns that he would try to introduce European-style labor practices and create problems.

Pio won. The sky would not fall in and the club would flourish during his tenure.

Nevertheless, the first thing he did after ordering the obligatory champagne to mark his victory was to announce that, henceforth, staff would be required to wear red underwear. He was joking, of course, but with Pio no one ever knew for sure.

He liked to be unpredictable. He relished being a “contrarian,” to quote one of his friends, and, with that endearing twinkle in his eye behind his trademark red-rimmed glasses, stir the pot. There was never a dull moment for anyone in his company.

Pio passed away suddenly when his heart gave out on February 6, at the far-too-young age of 68. We knew he wasn’t well and was suffering from the lingering effects of Covid-19. But Pio seemed indestructible. His passing, though not completely unexpected, still came as a shock.

His colleagues have characterized him as a “force of nature” with a “larger than life” personality. His editor at Sky TG24 described him as “inquisitive and courageous,” adding: “Every time there was an international crisis, a street protest, an earthquake or some other natural disaster, the phone call would come: 'If you want, I’m ready to go.'”

And he went – to China, to both Koreas, to Myanmar and elsewhere in Asia and to almost every place imaginable in Japan, covering breaking news spanning many years.

The Guardian's Jon Watts, Pio’s decades-long friend, said that Pio “was someone who lived vividly. He always brought color and flavor and passion to whatever he was doing, more so than I think almost anybody I've met. And that made him really interesting to be around. He was learned, intelligent and incredibly kind at times. He also cut corners in ways I would never dream of. But he was a good friend and someone who made the world a much more fun place to be”.

Anthony Rowley, another longtime friend who delivered what amounted to be a eulogy at Pio’s FCCJ memorial on February 15, characterized Pio as a “man of many parts. He was big in heart, big in warmth and big in personality and presence. He was dedicated to human rights and freedom. He was dedicated to free speech and by definition to the freedom of the press …. He would not hesitate to challenge what he saw as insincerity or untruth”.

All true. And while he was at it, he could be difficult, even with friends, sometimes especially with friends.

As is the case with many driven people, Pio was no saint. In his own words several months ago, he reflected that he had been “disturbing the perceived Japanese wa for four decades – first as a criminal lawyer and then as a journalist”.

Pio was a magnet for controversy, often initiated by Pio himself to draw attention to his many causes. And his causes included everything from getting the FCCJ management to buy an espresso machine to fighting Japan's discriminatory fingerprint laws - which targeted foreigners - opposing the death penalty and supporting workers' rights. He also fought to open up the kisha clubs to foreign journalists.

Pio was an activist. Whether it’s a good or bad thing for a news reporter to be an activist is subject to debate. But he stayed true to his beliefs to the end, dragging himself to moderate a panel discussion on the death penalty in Japan 10 days before his death, when he clearly wasn’t well.

One of the most notable controversies he initiated involved the George W. Bush administration’s decision to go to war in Iraq in spring 2003. Several weeks before the “shock and awe” campaign began, Pio placed a petition on the FCCJ’s noticeboard, urging members who opposed the war to sign their names.

Journalists are supposed to remain neutral and treat issues impartially and without bias, and there are good reasons for that. But it is by no means a universal standard and surely wasn’t one of Pio’s.

Predictably, he was challenged by a senior member of the American media establishment to remove the petition. The individual – there is no need to mention his name here – worked for an organization that had very strict rules about expressing opinions. Pio disagreed, and the debate eventually went public in a feature article in the Tokyo Shimbun, in which Pio, petition in hand with more than 70 signatures, made a compelling case that journalists should be able to express opinions about war and peace.

History, of course, went on to help his case by producing revelations of a massive US intelligence failure involving weapons of mass destruction and alleged American media complicity.

Any regrets, he was asked later? “None at all. Journalists are entitled to have opinions, and we should always err in favor of total freedom of expression.”

Italy’s other ambassador

It is hard to measure Pio’s legacy. Some chroniclers of Japan – Pio covered everything from the inner workings of Japanese politics to hot springs and sex clubs – have been influential. Others have been politically connected. Almost none of them – including Karel van Wolferen, Murray Sayle and Sam Jameson from an earlier era – had access to 21st century recording technology that Pio used so adeptly in his reporting.

Pio was essentially a citizen journalist. A night out with him could change in a moment if something of interest caught his eye. He would immediately switch into reporting mode and aim his camcorder, or in later years his iPhone, at the subject in question, followed by hours at home sitting in front of his computer editing his find.

He was, as one of his obituaries noted, a “fast and prolific writer”.

On television, he had a presence. Often wearing a scarf as part of his anti-establishment uniform (Pio could dress well), he went back and forth among languages – he spoke five, including Japanese – while covering demonstrations in Hong Kong, atomic bomb survivors in Hiroshima or interviewing the likes of Chinese dissident Ai Weiwei, the activist actor Richard Gere, anti-war writer/intellectual Noam Chomsky and Aung San Suu Kyi.

During the 2002 World Cup, he personally arranged for soccer legend Diego Maradona to speak at the FCCJ, going to Maradona’s hotel to seal the deal.

Born on July 18, 1954, in Rome, Pio arrived in Japan in 1979 as a young lawyer intent on studying comparative criminal procedure at a Tokyo university. Pio would adopt Japan as his home away from his native Italy.

We couldn’t nail down the exact date of his earliest connection to Japan, but we know that he established both professional and personal ties with Japanese radicals in those early years, specifically with the notorious Japanese Red Army.

His first connection to the FCCJ can be found on his membership application, where he listed previous consultancy work for the Parliamentary Commission for the Enforcement of the New Criminal Procedure Code in Rome (from January 1978 to January 1979) and employment at the Italian Institute of Culture in Tokyo (from May to September 1979) as his main career experience. He had graduated from the law department at the University of Rome in 1978.

Stamped as received on February 10, 1981, when he was 26, Pio’s application for regular membership listed his media affiliations as L’Espresso and Quotidiano Associati, both based in Rome. He was sponsored by Maria Romilda Giorgis, the Italian news agency ANSA’s Tokyo correspondent. Also sponsoring him was an officer at the Italian Chamber of Commerce in Japan, an organization Pio cultivated over the years, becoming the first editor of the chamber’s magazine, Viste, in 2006, and even serving on the chamber’s board of directors in 2010.

Pio would become a fierce crusader for Italian culture, in particular the country’s cuisine. He’s been characterized as an “ambassador” of all things Italian except the Catholic Church and the Italian right, although in the case of the church his feelings are nuanced. Guido Busetto, one of his early friends in Japan, recalled with a sense of irony that Pio, working as a freelancer in those early years, wrote for Avvenire, a newspaper affiliated with the “progressive wing” of the Vatican Council.

David McNeill, another friend, said that Pio, professionally, “seemed to know everyone”. That, he did. He would occasionally show pictures of himself slurping ramen noodles with the Dalai Lama, whose representative attended Pio’s memorial and said optimistically, while acknowledging Pio’s friendship with His Holiness and support for the Tibetan cause, that maybe Pio “will come back very quickly”. As what, he didn’t say.

Naoto Kan, another of Pio’s influential friends, was in attendance and recounted a phone call from Pio from Fukushima on the day after the March 11, 2011 earthquake and tsunami. Kan was prime minister at the time. Pio had ridden his scooter through the night to get to the area and was one of the first reporters on the scene, since Japanese media organizations had been ordered not to enter the area.

“But Pio did,” said Kan. “He didn’t care about the rules.”

His contact list is massive, from the rich and famous and politically powerful to the little guy, the most vulnerable among us. In a largely autobiographical article published on an online news site in Italy on the day of his passing, Pio in his own words identified the following accomplishments in his more than 40-year career:

- He is a journalist and writer and currently the East Asia correspondent for SkyTg24. He reported for various newspapers. including Il Messaggero, L'Espresso, Il Manifesto and, in Japan, the Tokyo Shimbun and Shukan Shincho.

- He was among the first journalists to reach Fukushima after the nuclear accident on March 11, 2011, published a book in Italian Tsunami Nucleare (Nuclear Tsunami), which was subsequently made into the documentary Fukushima: A Nuclear Story, which won a DIG film award in 2016.

- He served for many years as vice president of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan [five times to be exact], and in 2011 co-founded the Free Press Association of Japan together with Japanese journalist Takashi Uesugi.

- Since 2010, he has collaborated in the Press Office of the Permanent Secretariat of Nobel Peace Summit, which organizes the world meeting of the Nobel Peace Prize winners every year.

- In 2016, he won the Ischia Journalist of the Year Award in Italy.

- His most notable recollection was playing tennis with the former emperor of Japan – who was crown prince at the time – Akihito, winning a doubles match that pitted Akihito and his grand chamberlain against Pio and the Financial Times bureau chief at the time, Jurek Martin.

Pio is survived by five adult children, whom he doted upon, and his partner, Elisabetta Nepitelli Alegiani.

Roger Schreffler is a veteran business journalist and Wards correspondent who has covered the Japanese auto industry since the 1970s.