Issue:

Before arriving in China in 2006, Alison Klayman, like most people around the world, was only vaguely aware of the artist Ai Weiwei and his works. But her timing was fortuitous. A request from a friend to shoot video of Ai in 2008 coincided with his emergence as a fearless political dissident, as well as an internationally acclaimed artist.

The Philadelphia born film maker struck up a close friendship with Ai, now 57, shortly after the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. This was the moment when the artist/acitivist crossed the line from favored celebrity to hunted dissident by posting photos and comments on his blog criticizing corrupt officials behind the shoddy construction of schools that collapsed killing more than 5,000 children.

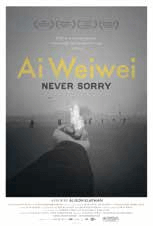

Klayman, 29, has had her lens trained on Ai ever since, and Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry is the documentary result. Her directorial debut has been described as “One of the most engagingly powerful movies of the year,” “stirring,” “important” and “riveting.” It won the Special Jury Prize at the 2012 Sundance Film Festival.

“I had already been in China for two years when I first met Weiwei, so I did not go there specifically looking for him or not even necessarily knowing who he was,” Klayman said in an interview shortly after her documentary was screened at the FCCJ on Nov. 12, an event also attended by producer Colin Jones.

“I met him in 2008 through my roommate, who was curating an exhibition of some of the 10,000 photos he took while he was in New York,” said Klayman, who plans to live in Tokyo for the next year. “My friend said it would be great if they had a video to accompany the exhibition, so we just struck an agreement that I would make the video but I would not be paid.

“Now I know how lucky I was, not just to meet him but also that he came to know me through me pointing a camera at him all the time,” she added. “From the very beginning, we hit it off.” Klayman said Ai cut a “very regal figure” and could go from being very serious to hilarious in a heartbeat.

“He liked to joke around and that was very appealing, but he can also be intimidating,” she said. “If there is something that he does not like, he will tell you. He is also willing to dive into political issues and I’d never heard such strong and directly critical comments from a Chinese citizen before.”

Curious whether speaking out against the government would get him into trouble, Klayman asked Ai why he had not already been arrested.

“He told me that in 2008 that a police officer had told him that if they wanted to get him, they could,” she said. “It would not have to be a political reason, it could be any reason they wanted. And in the end, he was detained for economic reasons.”

Initially, the monitoring of Ai’s activities was negligible, but Chinese authorities began to ramp it up as he spoke out about the Sichuan earthquake scandal. Undeterred by a severe beating by the police in Chengdu in Aug. 2009, he was briefly placed under house arrest in Shanghai in November 2010 while the authorities tore down his newly built studio in Shanghai.

One month previously, he had been frustrated in efforts to leave China as the government feared he might attend the ceremony at which fellow dissident Liu Xiaobo was to be presented with the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize.

Meanwhile, Ai blogged and Tweeted a constant stream of scathing social commentary and critiques of Chinese government policies.

“When I first met him, there were no surveillance cameras pointed at his front door, but when that happened he knew that he was making a choice, that he was crossing a line,” Klayman said. His life was no longer his own.

“But it was ridiculous to put cameras on his front door because he was Tweeting all the time,” she said.

Even though the atmosphere was intimidating, Klayman said that as a foreign filmmaker, she rarely felt personally at risk.

“In the film, we went to a police station to complain when he had been assaulted by the police and that was a little intimidating, but I was an accredited foreign journalist and I thought the most likely the worst that could happen was that I would be kicked out,” she said. “But Weiwei and other Chinese citizens were taking a much bigger risk.”

Klayman went to New York to edit the film in late 2010, with the opening of his exhibition at the Tate Modern in October 2010 acting as a bookend to the movie.

Ai was arrested on April 3, 2011, and held for 81 days before being suddenly released. The incarceration made him aware that he had a weak spot that the Chinese authorities could press at any time, Klayman believes, but she said his fundamental principles remain unchanged.

“He is passionate about some universal themes; free expression, transparency, the rule of law, respect for the voice of the individual and the individual’s life,” she said. “Those have not wavered and his core beliefs have not changed. After he was released, he told me that he would have to find a new way to play the game.”

Currently, the Chinese authorities refuse to return Ai’s passport.

“For an internationally renowned artist, that’s a big restriction,” said Klayman, adding that he has effectively been sidelined within China as well.

“He’s not covered in the domestic press and his domestic social media presence was shut down in 2009, so it has been impossible for him to maintain a blogging presence,” she said. “It’s hard to remain famous when you can’t reach people or when it is forbidden for others to write about you.”

Despite the handicaps, Weiwei is attempting to reach a new audience through his latest project, heavy metal music, even though he himself admits he has a bad singing voice.

“I think he will always believe in the possible and if you do that, you will always remain an optimist,” Klayman believes.