Issue:

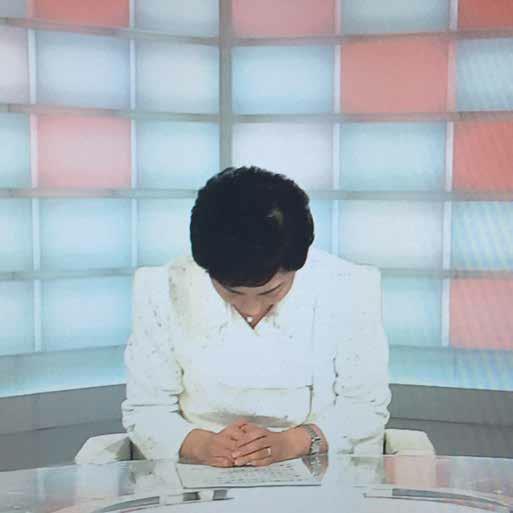

Hiroko Kuniya, no longer fronting NHK's investigative “Close-up Gendai”

The government is playing chicken with the media and winning, say experts.

On Jan. 21 this year, Tsuneo Watanabe, editor-in-chief of the Yomiuri Shimbun, hosted an evening dinner for Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and some of Japan’s top media executives at the company’s headquarters in central Tokyo. According to reports by people who attended, the companies represented included the Mainichi, Sankei, Asahi and Nikkei newspapers, along with the nation’s biggest broadcaster, NHK.

Writing in the Asahi Shimbun a few days later, journalist Akira Ikegami asked the obvious questions: Who pays when the country’s leader eats with the head of its most-read newspaper? “Does the Yomiuri owe Abe something? Enough to invite him for a meal? Did Abe meet with Watanabe because he wanted the Yomiuri to understand his viewpoints? Or did Watanabe give advice to Abe?”

Nobody is telling, though we have been here before: Six years ago, when Abe resigned from his first, unlamented term as prime minister, Watanabe brokered the appointment of his successor, Yasuo Fukuda. The Yomiuri kingpin then attempted to forge a coalition between ruling party and opposition. His paper, of course, neglected to tell its millions of readers about any of this.

Closed-door chats between media proprietors and politicians are nothing new. During the prime ministerial reign of Tony Blair, aging media tycoon Rupert Murdoch entered and exited Downing Street through the back door. Among the issues discussed was Murdoch’s support for the unpopular war in Iraq (all 175 of Murdoch’s newspaper editors backed the U.S./UK decision to invade in 2003) and Blair’s promise to soften his party’s commitment to media ownership laws that threatened Murdoch’s empire.

So perhaps we should not be too hard on the Yomiuri, or for that matter the Nikkei. Japan’s top business newspaper failed to report that its chief editorial writer was also at the Watanabe nosh-up, points out Ikegami. “Is that because the Nikkei didn’t want its readers to know,” he wonders. “Or, did the newspaper simply run out of space?”

ABE HAS BEEN AN unusually enthusiastic host. Last year, he dined with Watanabe several times, along with Yoshio Okubo, the president of broadcaster NTV, and the bosses of the Mainichi and Fuji TV. One meeting reportedly took place at the vacation home of Japan Foundation chair Yohei Sasagawa. All told, the prime minister has met on dozens of occasions with the country’s top media executives.

These gatherings violate any sense of distance between politics and journalism, says Michael Cucek, a political scientist at Temple University in Tokyo. “You cannot pretend that there is a media watchdog,” he says. “There is no concept of conflict of interest at all.” It seems only sensible to speculate, then, if they are related to the disappearance from the airwaves this month (March) of Japan’s most outspoken liberal anchors: Ichiro Furutachi, the salty presenter of evening news show “Hodo Station”, Shigetada Kishii, who had a regular slot on rival TBS, and Hiroko Kuniya, who helmed NHK’s flagship investigative program “Close-up Gendai” for two decades.

The weekly press blamed Kuniya’s downfall on an interview last summer with Yoshihide Suga, the government’s top spokesman and a close aide of Abe. Kuniya had the temerity to ask an unscripted question on the possibility that the new security legislation might lead to Japan becoming embroiled in other countries’ wars. By the standards of the sometimes spittle-flecked political clashes on British or American television the encounter was tame. But Suga’s handlers were reportedly furious.

KUNIYA HAS DECLINED TO discuss her removal though she did release an opaque comment on her resignation lamenting that “expressing things has gradually become difficult.” The show had been due a refit for years, say insiders; the audience was aging and the format stale. One of Abe’s first moves after he returned to power in 2012, however, was to appoint conservative allies to NHK’s board. Katsuto Momii, the broadcaster’s new president, subsequently raised eyebrows by questioning its independence. This new environment has encouraged self censorship at the broadcaster and left little space for the kind of critical journalism Kuniya represented, says Yasuo Onuki, a former senior reporter at NHK. “Of course, it is difficult to prove that she has been fired. The government is very good at constant, behind-the-scenes pressure.”

Furutachi has also kept mum about his decision to quit. Producers connected to the show and who have spoken anonymously, however, relate months of pressure against Furutachi’s on-air criticism of the Abe government. A climax of sorts came after Shigeaki Koga, a former industry minister bureaucrat, famously held up a sign saying “I am not Abe” to show his disagreement with the government’s handling of a hostage crisis involving Japanese citizens.

A few months later, Koga provided one of the year’s television highlights when he claimed live on-air that his contract was being terminated because of pressure from the prime minister’s office. His aim, he insists today, was to rally the media against government interference. Instead, the show’s producer, TV Asahi, apolo-gized and promised tighter controls over guests. “It shows that if you repeat a lie often enough people will believe it,” he says.

Kishii used his nightly spot on News 23 to question legislation last year expanding the nation’s military role overseas. His on-air fulminations prompted a group of conservatives to take out newspaper advertisements accusing him of violating impartiality rules for broadcasters. In January, he announced he was stepping down when his contact ended in March.

“Nobody said directly I was going because of my comments that’s not how it works,” says Kishii. He blames a whispering campaign by Suga. “He gives off-the-record briefings to journalists containing some criticisms of me,” he says. “These comments are relayed back to the management and it goes from there. Nothing is left on the record.”

BACKROOM POLITICAL PRESSURE ON the media is as old as printing presses. What is unprecedented, says Koga, is the government’s increasingly public intimidation of journalists. The latest salvo was the threat on Feb. 9 by Sanae Takaichi, the communications minister, to shut down TV companies that flout rules on political impartiality. Takaichi was responding to a question about the departure of the three anchors.

Those comments were merely “common sense,” said Suga. But they were enough to trigger an angry public response from Kishii, who came out fighting with some of the top liberal names in Japanese journalism. Soichiro Tahara, Osamu Aoki, Akihiro Otani, Soichiro Tahara and Shuntaro Torigoe all subsequently gave a press conference where they accused the government of trying to destroy the free media.

“To me, the most serious problem is self-restraint by higher-ups at broadcast stations.”

At the FCCJ on March 24, however, some were equally as critical of broadcasters and newspapers for failing to stand up to the government. “There has always been political pressure,” said Tahara, a veteran reporter with TV Asahi, responding to Torigoe’s criticism of government intimidation. “It’s not so much about political pressure, it’s about deterioration in the media. To me, the most serious problem is self restraint by higher-ups at broadcast stations.”

Producers at TV Asahi and NHK say the impact of the meetings between Abe and their bosses has been to weaken their organizations’ taste for a political fight with the government. The Asahi’s critical coverage of the Abe government arguably climaxed, for example, on May 20, 2014, when it published a story based on the leaked testimony of Masao Yoshida, the manager of the Fukushima Daiichi plant during the 2011 meltdown. The scoop claimed that 650 panicked on-site workers had disobeyed orders and fled during the crisis.

The Asahi’s claim, challenging the popular view of the workers as heroes who risked their lives to save the plant, was strongly contested by the industry, the government and Asahi rivals, particularly the right-leaning Sankei Shimbun, which blamed the confusion at the plant on March 15-16, 2011 on miscommunication. Finally, on Sept. 11, 2014, Tadakazu Kimura, the Asahi’s president announced the retraction of the article, the dismissal of the paper’s executive editor Nobuyuki Sugiura and punishments of several other editors. The highly damaging announcement pleased Asahi critics and stunned journalists at the newspaper who say they were kept in the dark beforehand.

LAWYERS, JOURNALISTS AND ACADEMICS expressed puzzlement at Kimura’s retraction. While the factual details of the Yoshida testimony were open to interpretation, there was little doubt that despairing on-site plant workers had abandoned their duties during the worst of the crisis. “The content of the article and the headline were correct,” insisted Yuichi Kaido, a lawyer who blames the retraction on political pressure. An independent press monitor might have settled the controversy but the Asahi relied on its in-house Press and Human Rights Committee to probe the story and discipline those behind it.

The Asahi’s mea culpa followed another even more damaging retraction a month earlier, over a series of articles in the 1990s on “comfort women.” Seiji Yoshida, the source for some of these stories, had long been discredited and the Asahi’s retraction was years overdue. Yet, the reaction on the political right was not only to question the newspaper’s entire reporting but to blame it for damaging Japan’s reputation abroad and poisoning ties with its neighbors.

It was notable that throughout the Asahi’s difficulties, Abe sided with its critics and declined to defend the principle of a broad, pluralist media including those that don’t always agree with the government line. That’s because the government has little tolerance for criticism, says Makoto Sataka, a political commentator and colleague of Kishii’s. “They view it as a nuisance,” he says. “They have a goal and they’re going to get there, and the media is in the way.”

Koga puts it more bluntly. The government is playing chicken with the media, he says, and winning.

David McNeill writes for the Independent, the Economist and other publications. He has been based in Tokyo since 2000.