Issue:

Four veteran reporters who returned to their old stomping ground in Tokyo agreed on one thing: these are both the best and worst of times for foreign correspondents.

DIGITAL MEDIA HAVE GIVEN reporters the technological wherewithal to report the news faster than ever; it has also spawned a new community of citizen journalists, whose reporting from war zones and trouble spots has, in some cases, rivaled that of the “traditional” media. From the Snowden revelations to accounts of the misery being visited on the people of Syria, journalists of all backgrounds continue to demonstrate why ours is a profession worth defending.

Yet journalism is also under attack. The number of reporters killed in the field rises by the year; intimidation and acts of violence directed at members of the media are spreading. Journalists in democracies such as South Korea and, yes, Japan, find themselves up against increasingly illiberal governments.

Last month, the FCCJ was fortunate to host former Tokyo correspondents with years of experience from both ends of the digital age and in postings all over the world. They can recall a time when they had to file to a daily deadline, but would probably never see their work in print until the arrival, weeks later, of an envelope of cuttings kindly collated by a newsroom colleague; and when disgruntled readers had to put pen to paper in a letter to the editor.

But they are familiar, too, with the ever-changing work environment that has forced “print journalists” to become multitaskers reporters, bloggers, videographers and photographers all the time under pressure from a growing number of new players and shrinking editorial budgets.

BILL EMMOT, THE ECONOMIST’S Tokyo correspondent from 1983-6, said the globalization of information had, perhaps counter-intuitively, made the role of the foreign correspondent more important than ever. “The world is more transparent, we face more competition in the provision of information, it is harder for politicians and other power holders to say different things to different audiences at home and abroad as was common in the 1980s but some things have stayed the same or gone backwards,” said Emmott, who in his book, The Sun Also Sets, predicted the bursting of the Japanese stock-market bubble.

Emmott cited the Eurozone economic crisis, migration and refugees, Russia and Ukraine as stories that demand cross-border coverage, only for much of the media to have been found wanting. “In Europe in that time, our media has, if anything, become more nationalistic, more nation-centered. Far too little cross-border and cross-cultural reporting and analysis has happened,” said Emmott, who as editor-in-chief of the Economist oversaw its emergence as the world’s most widely read international news magazine.

Emmott blamed the 2008 financial crisis for placing the media under much more pressure than could have been expected from the dawn of the digital media alone. The very existence of the open society was under threat, he added, from rising xenophobia and nationalism, evident in prevailing attitudes towards migration, trade and security, and embodied by the growing clout of politicians such as Marine Le Pen in France, Nigel Farage in Britain and Donald Trump in the U.S. “The open society is something that we foreign correspondents epitomize, and this threat to openness is what makes foreign correspondents more important than ever,” Emmott said. “The point of foreign correspondents has always been that to better understand foreign countries is to better understand our own. This craft is under attack and we must defend it.”

Defending press freedom can come at a cost, however. William Horsley, the BBC’s bureau chief in Tokyo from 1983- 90, said defensiveness and secrecy were common to all governments, but added that more journalists were working in an atmosphere of fear and intimidation.

“The new normal in journalism is to be watched and to be under attack from you-know-not-where,” said Horsley, who since retiring from the BBC in 2007 has become an advocate for journalists working in dangerous places.

HORSLEY, THE AUTHOR OF the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe’s 2014 Safety of Journalists Guidebook, said about 150 journalists were killed around the world last year. “But more sinister than that is why journalists are being killed and attacked,” he said. “It’s not only journalists in war zones, but also those who report on crime, corruption and major human rights abuses.”

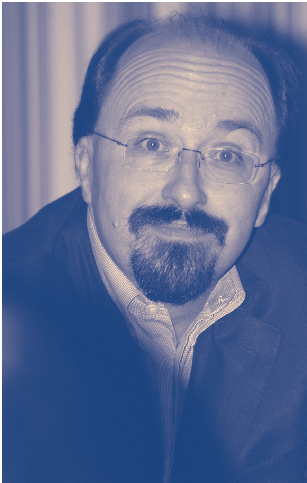

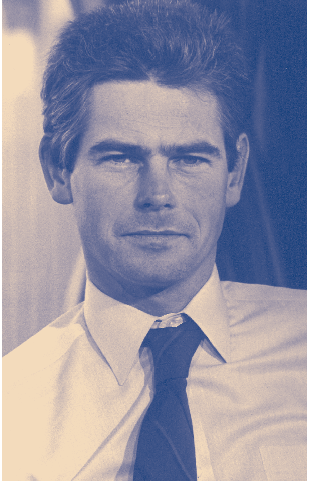

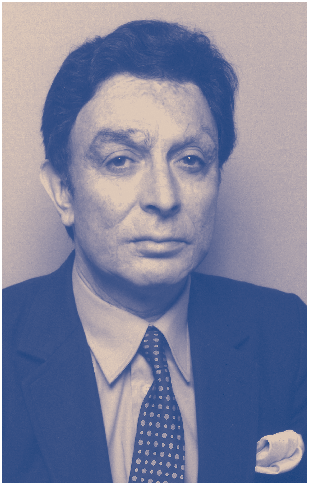

Left to right: Bill Emmott, William Horsley, Fernando Mezzetti, Philippe Ries

Despite the myriad challenges, reports of the death of journalism are premature, according to Fernando Mezzetti, Tokyo correspondent for Italian newspaper La Stampa from 1987-90. “In my view the foreign correspondent is more important than ever. He knows his country, he knows the situation,” said Mezzetti, who left Japan to cover the collapse of the Soviet Union as the paper’s Moscow correspondent.

He agreed that in highly dangerous trouble spots, notably Syria, citizen journalists were often the only available source of information, even though at times the accuracy of their work should be treated with skepticism. “My view is that no citizen journalist can replace the professional journalist, who has done the job of verifying the reality on the ground,” Mezzetti said. And while he acknowledged the current trend towards downsizing, he said, “I don’t agree that journalism is doomed to disappear.”

Commenting on the financial pressures facing media organizations, Philippe Ries, Agence France-Presse Tokyo senior correspondent (1985-89) and bureau chief (1998-2003), attempted to lift the gloom by drawing on his involvement in MediaPart, a successful French online investigative and opinion journal.

THE SUBSCRIPTION-ONLY SITE, launched in 2008, has almost 120,000 subscribers and racked up sales worth 10 million Euros last year, said Ries, who co-authored Shift: Inside Nissan's Historic Revival with Renault-Nissan chief executive Carlos Ghosn. MediaPart now employs 39 full-time journalists and a number of freelancers all over the world. “The idea was that we should be able to spend money on long-term costly investigations,” Ries said. While newspaper editors wrestle with the question of how to monetize content, Emmott agreed with Ries that survival lies behind a paywall. “It’s absolutely clear that the future of journalism is the subscription model. This is very good news for journalists, because the only thing that will persuade people to subscribe to something is the journalism,” Emmott said. “This should be the future for journalism, but of course it’s a hard transition. Old journalism was advertising, and subscription was cream on the cake; now it’s the other way around. And we have to persuade readers that they should subscribe.”

Discussion inevitably turned to Japan, and concern that the media are being targeted by an increasingly intolerant prime minister and his supporters. Only last month, the internal affairs minister, Sanae Takaichi, warned that broadcasters that repeatedly failed to show “fairness” in their political coverage, despite official warnings, could be taken off the air. That came weeks after news that three respected broadcasters with a reputation for asking tough questions would leave their jobs from April.

FROM COVERAGE OF EVERYTHING from elections to Japan’s diplomatic spats with China and South Korea and the question of Japan’s wartime conduct, official pressure on the domestic media is stronger than many reporters here can recall. “One of the key problems is self-censorship mixed with complacency,” said Emmott, although his criticism was not directed at Japan alone. “Sometimes it is overt conformism and self-censorship, which certainly happens in this country, but in other countries as well.

“I’m shocked,” he said, “by how little fuss there is in the British media about the kidnapping of the booksellers in Hong Kong and what’s been done with them by the Chinese authorities. It’s almost as if Hong Kong had never been a British colony. I’d say it’s been played down and almost completely overlooked by parts of the British media. It’s important that other media with the capability and resilience to speak out, do speak out.”

Fears that Japan’s government is resisting international scrutiny arose last December when it abruptly cancelled a visit by David Kaye, the UN special rapporteur for freedom of expression, saying it had been unable to arrange meetings with officials. Kaye is now scheduled to visit Japan in April.

“It’s very distressing to see that there was an obstacle to David Kaye’s visit last December,” said Horsley. “Watching Japanese TV, it’s hard to imagine anything more like baby powder than their coverage of news. If you don’t see politicians squirming, if they refuse to answer questions such as is happening in Turkey and is apparently happening in Japan you know that press freedom is not happening.”

Without proper funding, journalists struggle to resist the tide of official pressure, with their role as public watchdog suffering as a result, Ries said. “When resources are scarce, there are fewer journalists in the newsrooms and you cannot investigate properly. That’s where the freedom of the press is under threat,” he said.

Journalism’s future landscape will be an unforgiving place unless it continues to attract talented young reporters and editors. Fittingly, the session ended with a question about how best to carve out a career in a profession under siege. Horsley noted that the modern reporter must now “do absolutely everything yourself,” but pointed to the rise of BuzzFeed and Vice News as examples of organizations that have broken the mold created by the traditional Big Media. Ultimately, though, the same personal qualities that guided him and his colleagues throughout their careers are just as relevant today. “You have to be immensely agile, capable and ambitious,” he said, “and go out there and create your own specialty.”

Justin McCurry is Japan and Korea correspondent for the Guardian and the Observer. He contributes to the Christian Science Monitor and the Lancet medical journal, and reports on Japan and Korea for France 24 TV.