Issue:

By the outbreak of the Second World War, radio had become the main means of disseminating news by most of the belligerents. In Japan, thanks to the government monopoly on radio, controlling the contents of broadcasts proved far easier than monitoring the print media, and by the 1930s radio had become the main vehicle for news releases and propaganda from the Information Bureau.

In Valley of Darkness: The Japanese People and World War Two, historian Thomas R.H. Havens wrote that from 1934, all broadcasting stations in Japan had been absorbed by the public corporation, NHK. After the war began, the state expanded radio audiences by waiving the monthly subscriber fee of one yen for large families or families with men at the front. While Japan in 1938 had only one fourth as many radio receivers per capita as the US, authorities distributed receivers to poor villages, which could be shared by multiple listeners.

Havens writes:

Beginning in January 1938, the government broadcast ten minutes of war dispatches and news of the spiritual mobilization movement each evening at 7:30. Like Japan’s newspapers during the war, NHK carried few reports of the European theater even after the fighting began in September 1939, and the Domei press agency remained the only official source of news throughout the period. Controversial political developments were never reported, and starting from the day Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, weather forecasts were also suspended because they might provide the enemy with useful information.

Despite heavy wartime press censorship, a few news organizations made efforts to obtain and process what they could from the enemy’s perspective. At the Mainichi Shimbun, this was done by slipping in alternative facts obtained by illegally listening to foreign shortwave broadcasts, and attributing the material to Mainichi correspondents who had become stranded in neutral counties when the war broke out, in such cities as Stockholm, Zurich, Lisbon and Buenos Aires.

The memoir Fifty Years of Light and Dark: the Hirohito Era (1975), published by the Mainichi, contained this brief passage:

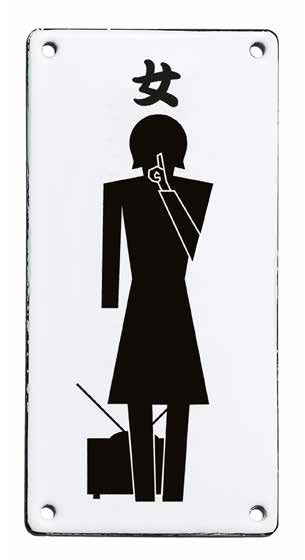

Staff members of the Mainichi Shimbun stealthily vanished into the women’s toilet, converted into a “black chamber.” They set up a monitoring apparatus inside the toilet converted into a sanctuary free from military inspection and listened to shortwave radio (forbidden to civilians at the time) to the BBC, Voice of America, Treasure Island, Ankara, and other foreign broadcasts.

The news obtained was circulated among the editors of both the vernacular and the English newspapers. Some of it was printed under the datelines of neutral countries...where there actually were Mainichi correspondents...This valuable but highly secret newsgathering activity was given an inglorious name, Benjo Press.

A Mainichi Shimbun article dated June 22, 2015, shed further light on details of the operation. On December 8, 1941, the day the war began, all newspapers were deprived of their means of obtaining news from overseas. In the Mainichi’s case, this included news from its reciprocal agreement with America’s United Press. The same day, a secret emergency meeting was convened at the newspaper’s office, at which a decision was made to monitor shortwave radio broadcasts. In order to preserve secrecy, a women’s restroom on the 3rd floor, adjacent to the newsroom, was cordoned off and converted to that purpose.

“On the wall outside the converted toilet, a wood fuda (name tag) identified the department as the Obei Besshitsu (Europe America section annex),” the Mainichi reported. “The door was reinforced with a second layer of insulation to prevent sounds from leaking out, and black velvet curtains were strung on the windows. There was also a bunk bed where shift workers could repose.”

The late Zenichiro Watanabe, a member of the newspaper’s Europe America section, recalled that the monitors consisted of a team made up mostly of eight nisei reporters in their late 20s or early 30s holding dual nationality.

ON THE DAY THE WAR BEGAN, ALL NEWSPAPERS WERE DEPRIVED OF THEIR MEANS OF OBTAINING NEWS FROM OVERSEAS.

Since signal reception was generally poor during daytime hours, the team would monitor frequencies late at night, listening to broadcasts from the US, UK, France, Germany, the Soviet Union, Turkey, Australia, China and others. They scribbled down notes as they listened to news, advertising, and propaganda broadcasts. Their notes were then typed up. Staff in the annex would push a button, sounding a bell in the editorial section, summoning a messenger, who would collect the transcription. At the editors’ prerogative, material to be used in the print edition would be translated into Japanese.

The people engaged in these tasks had been sworn to secrecy. Insiders coined the name Benjo Tsushin (toilet press), which came into use in house. The foreign broadcasts enabled Mainichi management to keep abreast of the global news while obtaining a grasp of what military headquarters was concealing.

For example, in the case of the Battle of Midway, which took place on June 5-7, 1942, foreign radio stations repeatedly broadcast news of the “decisive defeat of the Japanese fleet,” with the sinking of four carriers, including Admiral Nagumo’s flagship, Akagi. On June 10, the broadcast issued by Japan’s military headquarters made no mention of the loss of the carriers, along with some 300 planes, but rather reported it as a victory.

While the Mainichi Shimbun editors were aware of the contradictory reports, the newspaper’s issue of June 11 was under a number of legal restrictions controlling the news media and public security, and had no choice but to parrot the military’s announcement.

Materials from the toilet press reported to the Mainichi management judged unsafe to use were stored in a paper bag and treated as top secret. Late editor in chief Motosaburo Takada recalled, “Newspapers were completely under the control of national policy, and became nothing more than ‘bullets of paper.’ Even toward the end of the war, they proclaimed that white was black, concealing the reality of defeat. The toughest thing for us was to keep printing lies in order to uphold fighting spirit.”

But sometimes the newspaper was able to slip in information in the form of tokuden (special wires) claimed to have been filed from Lisbon, Stockholm, Zurich or other neutral countries—which were actually compiled from radio transcriptions received in the company’s HQ building in Tokyo.

Via the shortwave broadcasts, “Toilet Press” was able to monitor particulars from the battles in Europe and at Guadalcanal, the death of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the Yalta Conference, and the Potsdam Conference.

On May 7, 1945, German Chancellor Admiral Doenitz had formally announced unconditional surrender of all German armed forces via radio. In its morning edition of May 9, 1945, the Mainichi Shimbun reported Germany’s unconditional surrender, with the report credited to an overseas correspondent.

Thanks in part to its proximity to the palace, which was off limits to U.S. bombers, the Mainichi headquarters building in Yurakucho was undamaged by air raids. The secret unit’s work continued through the end of the fighting, but staff began urging it be shut it down because some felt, inexplicably, that “Things might go hard on us if the Americans find out about it.”

On or about August 20, 1945, the toilet was restored to its original purpose.

Given the unbridled power of the secret police and military authorities during wartime, one wonders how the Mainichi succeeded in concealing its secret unit for as long as it did. Actually, it’s quite possible that it didn’t.

In March 2000, Taketoshi Yamamoto, professor of history at Hitotsubashi University, published a paper on communications in which he cited postwar testimony by a certain Kempeitai major, referred to only as “Tsuneyoshi,” who claimed to have been aware of the shortwave monitoring activity. And the Mainichi, apparently, was not the sole offender.

“I personally did not listen to any broadcasts, but I clearly remember that several Tokyo newspapers (Asahi and Mainichi at least) had receivers,” he testified. “It was decided to let them monitor the broadcasts.”

The Kempeitai major claimed that nearly all officers ranked above field grade (major) knew about the monitoring of foreign broadcasts. He also remarked that some members of the military who were party to this information shared details selectively with civilians.

“While in Hokkaido in March 1945, I often heard comments about broadcasts from Saipan,” he was quoted as saying. “Most of the leaders of the government and military listened to them every day. However ordinary people didn’t have receivers that could pick up such broadcasts. So it became natural for soldiers to leak bits of information to civilians.”

Once Japan emerged from national seclusion in the mid 19th century and energetically sought out knowledge about the wider world, not even the draconian restrictions imposed by the military government could eradicate its appetite for news and information from abroad. While limited in its influence on the public, the three and one half year existence of the Mainichi’s clandestine “Toilet Press” stands out as a notable example of civil disobedience conducted by Japanese media organizations and individual reporters during the war years.

Mark Schreiber currently writes the “Big in Japan” and “Bilingual” columns for The Japan Times.